With my grades submitted, and evaluations received, I have now had (as promised) the opportunity to reflect on my first year of teaching. Here are the syllabus, examinations, and evaluations for the four classes I taught this year:

Fall 2012

- Property II (two sections): Syllabus, Exams, Evaluations (Day Section), Evaluations (Evening Section)

Spring 2013

I post this personal information for several reasons. First, I am in favor of transparency (the evaluations have been posted on my CV for a few months now–I only now have the distance and clarity to write about them). Second, in the event that any of my former or future students read this, it may help explain how I approach the class (I will give an overview on the first day of class). Third, if other new professors come across this post, and they have had similar experiences, perhaps they can learn from my mistakes, or (please!) give me advice to tell me what I’m doing wrong. But more importantly, I write this for myself. I view my teaching as an art. I want to get better. Posts like this, which I may make a yearly tradition, should help me keep track of my objectives, and hopefully accomplish them.

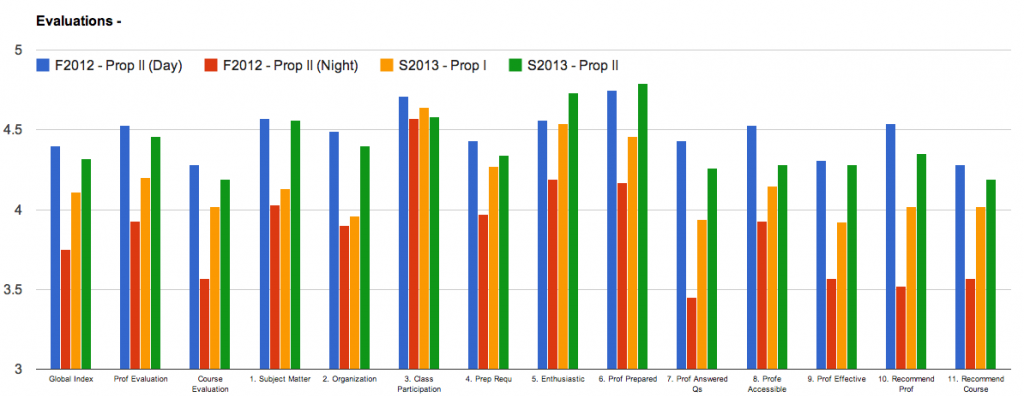

I have summarized my teaching evaluation scores in this graph, along the 14 dimensions recorded, for each of the 4 classes I taught: Fall 2012 Property II, Fall 2012 Property II, Spring 2013 Property I, Spring 2013 Property II.

Let me start by comparing my expectations at the beginning of the year, with my observations, and I will conclude with some thoughts on how to improve the class for next year.

First, this was my first time teaching a large lecture class (I had between 45 and 86 students in my 4 sections). Along with Judge Gibson, I had taught three small seminars (10-12 students). A large lecture class presents a very difficult dynamic. I wasn’t sure how my teaching style, which tends to be very informal and conversational, would translate well to the big class.

I adopted a method of class participation from my former professor, and current Texas Solicitor General, Jonathan Mitchell. In a small 12-person seminar on Habeas, Mitchell would start with a random person, and move around the room, asking each person one question, then moving on. It is the exact opposite of Socratic, which stays with one person indefinitely. I really like this approach, as it ensures that everyone can participate, and people must be aware of what’s going on. It also fits my personality, which tends to be very fast-paced. I employed this approach in my lecture classes. I would start with a student, and move up and down the rows, asking each person one question (and perhaps a follow-up). The next class, I would start with whoever was on deck in the previous class, but didn’t go (thankfully, students would readily volunteer that they were next). This approach has several pros and cons.

On the plus side, I can talk to, and hear from a lot of students every class. The conversation is always lively. On a good day, where I don’t lecture much (something I try to keep to a minium), I am able to call on all 80 students. Students know that they can be called on, and have an incentive to be prepared. (I keep the readings to a manageable 20-30 pages per class, so it is quite doable). Also, by hearing from many students, and not just the unlucky person on a call, I can get a better sense of what is confusing/not working, and readjust.

The negative side is that it avoids the developmental aspects of the Socratic method. By staying with one student, you watch her squirm and meander her way towards the right answer. I can accomplish this somewhat by asking one student after another follow-up questions, that are Socratic-esque, but it is harder when you break it up among multiple people. The flow is tough to maintain. Relatedly, with the approach I use, when a student gets an answer wrong, or the answer is incomplete, I don’t stay with the student, and move onto the next person. This allows a student who isn’t prepared to just bumble through an answer, knowing that I’ll move on–though I usually will come back to someone later who blows off the question.

This approach may leave behind the students who choose to come to class unprepared. Please note that I am not talking about students who did the readings, but have trouble answering a tough question. I know the difference (bringing your commercial outline to class is a good sign) But, at the same time, it more effectively stimulates the minds of the majority of the class who come prepared to learn. This is a tradeoff I’ve given much thought and I don’t know how I feel yet. Admittedly, the students who don’t prepare for class (I know who they are) will take the most time to grasp the material in class (assuming this is even possible). Holding their hand in class takes a lot of time and takes away the time from discussion and application for the rest of the class.

Also, it frustrates other students who want the right answer, and don’t like dwelling on wrong stuff. Though interestingly, students resent when their classmates are not prepared. I think this arises from some sort of jealously or resentment, that they didn’t have to do the same hard work, or perhaps a broader sense of fairness, in that it’s not fair that I did the work and they didn’t. Some professors find it an affront to them that a student didn’t prepare. I don’t care about that. No sweat off my back.

I will try to convey to the students early on, that when grading on a curve, they should celebrate their fellow students who don’t prepare for class. (This is something students at GMU seemed to internalize instinctively). On our bell curve, between 9% and 16% must get a C or below. I try to keep this closer to 10, but it may go as high as 15 (the more As I give out, the more Cs I have to give out to balance it to keep the average mean in the range). That means that 85% of the class is getting above a C. There is an almost one-to-one relationship between students who perform poorly in class, and perform poorly on the exam. There are some outliers, but generally the pattern holds. When a student consistently bombs out in class, and doesn’t seek help to improve, that student is probably going to fall towards the bottom of the bell curve. Grading on a curve, I have no choice. Between 9 and 16% must get C or lower.

So what does this mean for class discussions? My initial instinct is to raise the level of the discourse to appeal to the 85% who are in the game, but I recognize that this leaves the bottom 15% in something of a lurch. But what should these students expect? It is (painfully) obvious many do not do the readings, skip class, and never bother asking questions or coming to office hours. If they can’t prepare, what should be done for them in a jam-packed 90 minute lecture?

For next semester, I will soften my approach from moving on from students who are unprepared or give a bad answer, and dwell on them a bit longer to help reinforce the ideas. This will address, in part, any feelings of fairness or jealously that students may have. . But I will still try to keep the pace up, and not make catering to the unprepared students a focus of the class.

A related issue is teaching black-letter law. I think 1Ls have this unhealthy hunger for black letter law. I received some (but not a lot) of comments asking for more black-letter law in class. Property, unlike other first year classes, such as Torts (governed by a Restatement) or Contracts (governed by the UCC), or ConLaw (governed by the Constitution–wait, never mind), is almost entirely common law based. It is stultifying to try to reduce topics like future interests (in both the grantee and grantor) or the rule against perpetuities to some generally applicable rule. I can see the frustration on their faces when I tell them that they will just need to memorize certain concepts (such as pairings of future interests), and there is no good way of conceptualizing it.

This year I think I focused way too much on case law, and didn’t do enough explanatory questions (I saw this when grading exams, and certain topics were consistently missed–that’s on me). Next time I teach Property, I will try to walk through many more examples and hypotheticals in class. This will probably cut into the time talking about cases, which I will have to balance out. I think these will be more helpful than reciting blackletter law from a hornbook (which tends to confuse me more than help).

One of my more bold experimentations involved technology in the classroom. The reception by the students was also mixed, though I was pleased with the results from my end.

First, I recorded all lectures, and posted them on youtube (Google+ Hangout is a great and easy way to accomplish this). Some students really appreciated it, as they could watch lectures they missed, or rewatch lectures before exams. Other students complained, and said that it wasn’t fair that students could miss classes and just watch them later online (similar sentiments towards students who come to class unprepared). Due to the magic of YouTube analytics, I am confident that this concern is not grounded in fact. The number of people actually watching the videos (in Texas) is not high. Further, very few, if any, actually make it through till the end of the video (yes, I can track minute-by-minute what you watch). There very well may be people who brag about skipping class and only watching the YouTube videos (law students tend to be cocky like that), but this is a very, very small number. And for those who watch it, I know they are not getting the full value of the in-class experience because my microphone does not pick up answers given by students. All you here is a one-side conversation. It is not a perfect substitute, and I think any student who bothered to watch the videos would know that.

I think, broadly stated, the fairness argument bothers people. How is it fair that I go to class and someone else can watch the videos. I think this concern could be largely muted. After the names on the exams are released, I match up the students who perform the worst with the students who missed the most class. There is almost a direct correlation. Students who skip class do poorly. This is the 15% I addressed above. So I am not too concerned if this 15% attempt to watch the videos. I know they don’t really watch all of them, and even if they do, it providing the full classroom experience. If I explain this to the students, it will likely address a lot of the unfairness claims. A bigger life lesson is that life isn’t fair. Most people who try to take shortcuts won’t succeed, and those that can take shortcuts and still succeed have a special gift. My thoughts on attendance in class are fully developed here.

Second, in class I leave a “live-chat” projected onto the screen. I described it in this post. Basically, it is a twitter-like chatroom that allows students to post comments. I use this for a number of purposes. Students can post questions, links to interesting news stories, or make comments while I am lecturing. It democratizes the 80-person lecture in a powerful way. At the podium, I have the discretion to discuss a comment when it fits into my lecture, or ignore it altogether. I find it really effective from my perspective.

The reception to this was also mixed. Some students really appreciate it, but others say it is distracting. (Fascinatingly, one class this semester consistently liked it, and the other class consistently did not like it–I think there are some cultural memes that circulate around the class that coalesce in many of these comments). The sense I got from those who did not like it was that it was distracting–what invariably happens is that students post jokes to the board. Personally, I like the jokes, and find that it adds levity to the class, but I can see why people may not like it. There is an easy fix here. In the past, I allowed pseudonyms to encourage participation, and questions a person may be embarrassed to ask. Next semester, I will require students to sign their actual names, or at least first names (to avoid a google footprint) to comments. Signing names decreases participation, but gets rid of trolling (a lesson any blogger should know well). And, if I see that someone is putting up inappropriate comments, I will address it in class.

Next year I will be teaching Property I twice, Property II once, and in the spring I will teach Constitutional Law. A number of students highlighted the fact that I am a new teacher, but appreciated that I was trying to improve my craft. In my mind, these were some of the most important comments. I hope to improve the class even more in the future.