I recently completed the manuscript for my article, Presidential Maladministration. I have hesitated putting it on SSRN, because it will need some tweaks in light of the election. (Because it is cited in FN 431 on p. 294 of my Harvard Law Review piece, I had to deposit an earlier draft in the HLS library). The thesis argues in short, that courts should express some degrees of skepticism when the White House is involved in the regulatory process. I take exception with then-Professor Kagan’s article Presidential Administration, which argues that courts should be even more deferential when the President leaves his fingerprints on a rulemaking.

One species of presidential maladministration I write about will soon become extremely relevant–what I call “Presidential Reversals.” Here is a portion of that paper, which I will be referring to in future blog posts.

The first species of presidential maladministration is by far the most commonplace: when the incumbent administration abandons a previous administration’s interpretation of a statute. Every four-to-eight years, to comply with the new President’s regulatory philosophy, political appointees in agencies alter certain interpretations of the law—often with direction from the top. These changes are not always implemented through the formal notice-and-comment process, but rather are manifested through informal opinion letters, guidance, and even legal briefs. Regardless of their form, these presidential reversals are the ultimate, and clearest forms of commander-in-chief nudging to the administrative state.

There is nothing nefarious about a new administration disagreeing with a previous administration. Indeed, it is quite natural that presidents see things differently. The only question that remains is how should courts treat this reversal. Outside of Chevron’s framework, the Court has maintained that presidential reversals are “entitled to considerably less deference.”[1] In recent years, the Roberts Court—led by the Chief Justice himself—has faulted the Solicitor General’s abandonment of earlier positions “upon further reflection.” However, within the cozy confines of Chevron’s domain, old interpretations of ambiguous statutes are not “written in stone,” so “sharp break[s] with prior interpretations” do not weaken deference. Both blends of reversals are policy decisions all the way down, and should give courts pause that the newly-minted interpretation is any more reasonable than the abandoned on.

…

Perhaps the most visible manifestation of a presidential reversal is the phrase “upon further reflection.” This is a euphemism the government invokes to indicate that it is abandoning an earlier position for a new one. Tony Mauro, veteran Supreme Court reporter for the National Law Journal, pointed out that in the Solicitor General’s office, “upon further reflection” is usually understood to mean “upon further election.”[1] This phrase has primarily been used by the Solicitor General to alter a position the Justice Department took earlier in the lower courts during the course of litigation.[2] However, at times, the phrase “further reflection” has been employed as a euphemism for “the new administration sees things differently.”

For example, in a 1985 brief to the Court in Evans v. Jeff D., President Reagan’s acting Solicitor General rejected a position taken by President Carter’s Solicitor General involving attorney’s fees in civil rights actions[3] in White v. New Hampshire Dep’t of Employment Security.[4] “Upon further reflection, and with the benefit of nearly four years of experience under the Equal Access to Justice Act,” the brief stated, “we have concluded that our earlier suggestion was impractical and that the ethical concerns, though not insignificant in particular cases, are neither so frequent nor so intractable as to call for the per se rule adopted by the court of appeals.”[5] The reference to “nearly four years” is a clear repudiation of the statement made by President Carter’s holdover Solicitor General, over three months after President Reagan’s inauguration. This is a quintessential example of a presidential reversal following “further reflection.” Ultimately, the Court did not reach this issue in Evans.[6]

I was not able to locate any usages of the phrases “further reflection” from the Solicitors General in the Bush, Clinton, or Bush Administrations. However, for three cases argued during the October 2012 term, the Obama administration engaged in some deep reflection. In Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum, a group of Nigerian nationals living in the United States brought suit “alleging that the corporation [defendants] aided and abetted the Nigerian Government in committing violations of the law of nations in Nigeria.”[7] The Court granted certiorari to determine whether it could “recognize a cause of action under the Alien Tort Statute (ATS), for violations of the law of nations occurring within the territory of a sovereign other than the United States.”[8] The ATS, enacted as part of the canonical Judiciary Act of 1789, provides that “[t]he district courts shall have original jurisdiction of any civil action by an alien for a tort only, committed in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States.”[9]

In 1795, Attorney General William Bradford issued an opinion interpreting the ATS.[10] In the 2008 case of American Isuzu Motors, Inc. v. Ntsebeza, the Bush Administration’s State Department read Bradford’s opinion to confirm that ATS claims could not be brought for conduct “in a foreign country.”[11] Citing the Bradford opinion, then-Solicitor General Paul Clement told the Court that “The presumption against extraterritorial legislation was well-established at the time the ATS was adopted.”[12]

After the change in administration, however, that position flipped. In his brief, Solicitor General Donald Verrilli explained that “on further reflection, and after examining the primary documents,” the State Department “acknowledges that the opinion is amenable to different interpretations.”[13] Now, the government concluded that the ATS “could have been meant to encompass . . . conduct” outside the United States.[14]

During oral arguments, when the Solicitor General articulated that the “ATS causes of action should be recognized,” Justice Scalia interjected. “That is a new position for the State Department, isn’t it?” Verrilli replied, “It’s a new–.” Justice Scalia interrupted him again. “Why should we listen to you rather than the solicitors general who took the opposite position . . . not only in several courts of appeals, but even up here.” The Solicitor General replied that the United States has “multiple interests,” including “ensuring that our Nation’s foreign relations commitments to the rule of law and human rights are not eroded.” He continued, “It’s my responsibility to balance those sometimes competing interests and make a judgment about what the position of the United States should be, consistent with existing law. And we have done so.”

Justice Scalia, once again interrupted the Solicitor General. “It was the responsibility of your predecessors as well, and they took a different position. So why should we defer to the views of the current administration?” With a dash of humor, Verrilli answered, “because we think they are persuasive, Your Honor.” Over laughter, Scalia answered, “Oh, okay.” Chief Justice Roberts was not persuaded. Reaffirming Scalia’s position, Roberts warned, “whatever deference you are entitled to is compromised by the fact that your predecessors took a different position.” Ultimately, agreeing with the government’s new position, the Court determined that “Attorney General Bradford’s opinion defies a definitive reading and we need not adopt one here.”[15]

In Levin v. United States, the second case in this reflection trilogy, the petitioner suffered an injury at a Naval Hospital, and sued the United States for a battery.[16] The Federal Torts Claim Act (FTCA) generally waives the Government’s sovereign immunity from negligence, but exempts intentional torts.[17] Levin claimed that the Medical Malpractice Immunity Act, commonly known as the Gonzalez Act, permitted him to bring suit against the United States for a battery.[18] In the 1990 case of United States v. Smith, the government rejected this construction of the Gonzalez Act.[19] Solicitor General Kenneth W. Starr’s brief told the Court that the FTCA was the exclusive remedy for such claims, and suits in federal court were not available.[20] The Supreme Court in Levin noted that its prior “decision in Smith was thus informed by the Government’s position.”[21]

After several changes in administration, however, that position flipped. In 2012, the government “disavow[ed] the reading of [the statute] it advanced in Smith.”[22] In a footnote, Solicitor General Verrilli stated expressly, “The government does not adhere to the statements in that brief” filed in 1990.”[23] Amicus curiae—appointed by the Court, because the United States agreed with the lower-court’s judgment—flagged this sudden reversal. “When every reader comes away with the same understanding of a provision,” amicus wrote, “it is powerful evidence that the shared understanding is the provision’s natural meaning.”[24] The friend-of-the-court added, “The government offers very little in response” to the explain the change after “remain[ing] consistent for many years.”

During oral arguments, Justice Kennedy asked the Government about changing its position concerning a “central theory for your interpretation of the Act.” He joked, “I know you would have been disappointed if we didn’t ask you about this.” Deputy Solicitor General Pratik A. Shah replied, “Yes, you are correct . . . This is a change of position. We revisited it.” Ultimately, the Court “agree[d] with the Government’s earlier view, and not with the freshly minted revision.”[25]

The final case in this triad was US Airways, Inc. v. McCutchen. The appeal considered whether an employee who recovered damages from a tortfeasor was required to reimburse his health benefits plan for the entire amount it had previously paid out, including attorney’s fees.[26] The employee argued that the so-called “common-fund doctrine,” would override the express terms of the policy, and allow him to withhold his attorneys fees from the reimbursable amount. In 2003, the Solicitor of Labor filed an amicus brief with the Supreme Court expressly rejecting this equitable defense, urging the Court to enforce the terms of the plan.[27]

After the change in administrations, that position flipped. In the government’s 2012 brief in McCutchen, the Solicitor General explained that “upon further reflection, and in light of this Court’s discussion” in a 2011 ERISA decision, “the Secretary [of Labor] is now of the view that the common-fund doctrine is generally applicable in reimbursement suits” under ERISA.[28] This is the exact opposite argument the Labor Department advanced nine years earlier.

During oral arguments, Chief Justice Roberts criticized Deputy Solicitor General Joseph R. Palmore about this reversal. “The position that the United States is advancing today,” Roberts said, “is different from the position that the United States previously advanced.” The Chief, with a tinge of annoyance in his voice said “further reflection” was “not the reason” why the position change. He added for emphasis, “it wasn’t further reflection.” Roberts, who had served in the Reagan and Bush administrations decades ago, asked rhetorically whether the real reason was that “we have a new secretary now under a new administration, right?” Palmore attempted to answer, “We do have a new secretary under a new administration,” but Roberts interrupted him. “It would be more candid for your office to tell us when there is a change in position that it’s not based on further reflection of the secretary. It’s not that the secretary is now of the view — there has been a change.”

Kiobel, Levin, and McCutchen, each raising the same issue, were argued during a span of four months. Sensing a disquieting trend, Chief Justice Roberts sent a message of sorts to the Obama administration: “We are seeing a lot of that lately. It’s perfectly fine if you want to change your position, but don’t tell us it’s because the secretary has reviewed the matter further, the secretary is now of the view. Tell us it’s because there is a new secretary.” Palmore responded that since the earlier brief was filed, the “law has changed.” The Chief Justice replied, “Then tell us the law has changed. Don’t say the secretary is now of the view. It’s not the same person. You cite the prior secretary by name, and then you say, the [new] secretary is now of the view. I found that a little disingenuous.” The Chief openly rebuked the Solicitor General’s office for using this malapropism to justify maladministration. Supreme Court advocate Roy Englert Jr., who worked in the Solicitor General’s office, observed that Chief Justice Roberts was “making a broader point” with his criticism, referring to the recent string of cases where the Obama administration had reversed prior positions.[29]

…

The presidential reversal is not only the most common exercise of maladministration, but is also the most innocuous. First, it is completely transparent—and at times, nakedly so. In Kiobel, US Airways, and Levin, the Solicitor General flagged President Obama’s reversals through the phrase, “upon further reflection.” Even when the government does not use that phrase in a brief, it is not difficult for a reviewing court—at any level—to compare how previous administrations considered the same issue. In most cases, the parties challenging the reversal will be quick to raise these departures. In Chevron, State Farm, and Rust, it was utterly obvious that the positions changed when a President of a different party took office. Specific evidence that President Reagan told his cabinet to disregard Carter-era regulations is unnecessary. This form of administration is readily apparent, and the Court recognized it. Like any late-night infomercial, the Court proved adept at applying this before-and-after framework in Watt, Cardoza-Fonseca, Georgetown, and Good Samaritan.

Second, in cases of a presidential reversal, judicial review always remains as a valid check. When a new administration alters an old interpretation, someone will draw the short straw. In State Farm, for example, insurers would lose out on the savings that resulted from the passive safety measures. In Chevron, environmental groups would lose out from laxer emission standards. In Rust, doctors would lose funding for providing family planning services. These injuries suffice to constitute Article III standing. As a result, courts can review, and potentially reverse reversals that are unworthy of deference—whether they are unreasonable under Chevron, or arbitrary and capricious.

Presidential reversal only becomes problematic when it is combined with presidential discovery or nonenforecment. This tandem approach transcends an agency interpreting statutes in news ways. Rather, as we will discuss in the next section, this form of maladministration emboldens the White House to expand its jurisdiction, or confer substantive rights, or exercise abstention, in ways that are incompatible with congressional design. In some instances, where parties benefit, and none are injured, judicial review to check arbitrary exercises of power is unavailable. For such cases, standing is the government’s greatest, and only defense.

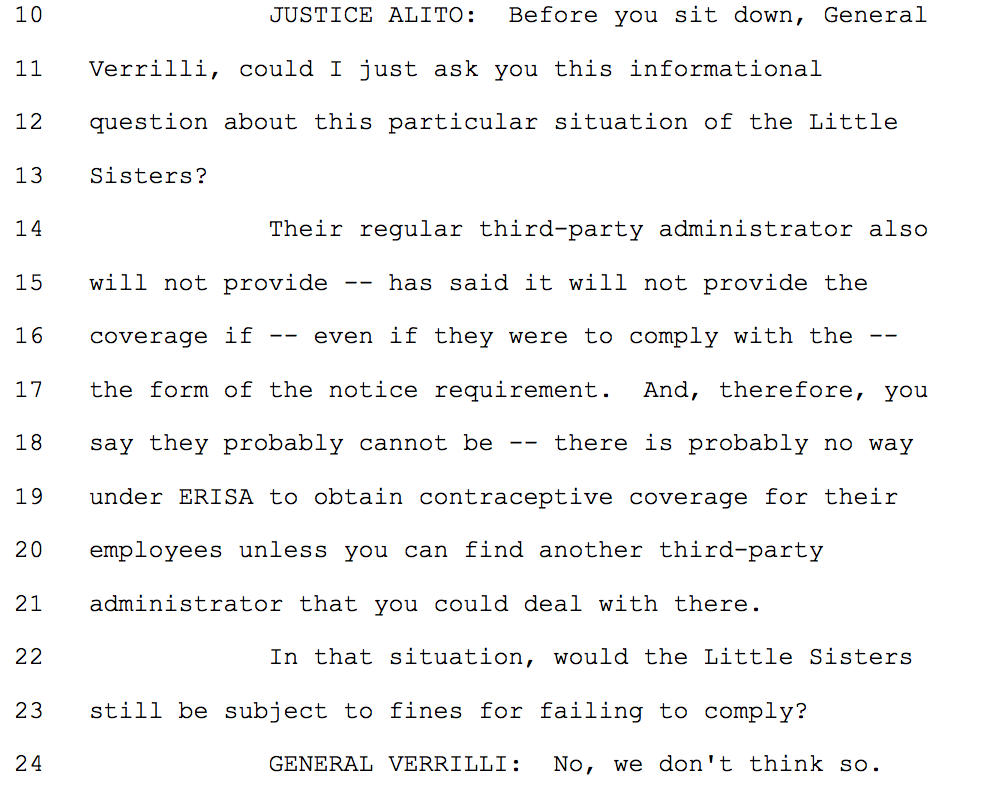

I fully expect (and hope) that the Trump Administration will reverse a number of President Obama’s policies. But in doing so, the next Solicitor General should not only say they changed upon “further reflection,” but articulate what the new administration has determined that they are unlawful. I suggest that this should be done with respect to immigration and the contraceptive mandate in this post.