Earlier this week I published a high-level piece in National Review explaining how the election will likely shrink the Court’s docket with respect to U.S. v. Texas, Gloucester County v. GG, and Zubik v. Burwell. In this post, I will delve into the details of how I see these issues winding down in light of the change in administration.

U.S. v. Texas

It should come as no surprise that on January 20, President Trump will almost certainly rescind DAPA. That would put an end to the U.S. v. Texas litigation, which is currently parked in Judge Hanen’s court in Brownsville. (I am still grateful I had the chance to visit in August). What remains to be seen is how the policy is cancelled. For reasons that I will discuss in a forthcoming piece titled Presidential Maladministration (to be submitted in the spring review period, after some timely tweaks), it is suboptimal for one administration to reverse the interpretation of a statute of a previous administration, simply because of a disagreement over policy. This practice, which I refer to as “Presidential Reversals,” is looked upon somewhat skeptically by the courts outside the context of Chevron. (Within Chevron’s domain, presidential reversals are optimal). The better route is to change a position because a subsequent administration determines that the prior position was unlawful. DAPA, perhaps more than any other Obama-era executive policy, screams for this affirmative repudiation.

On January 20, the President should direct his new Homeland Security Secretary to withdraw Secretary Johnson’s 11/20/14 DAPA memorandum. Simultaneously, the Office of Legal Counsel should formally withdraw its 11/20/14 DAPA opinion. In doing so, OLC should explain that it has now determined that the 2014 opinion was wrong, and that DAPA is both procedurally and substantively unreasonable. It would be sufficient to cite Judge Smith’s opinion for the 5th Circuit. (Judge Smith’s opinion did not address the Take Care clause–something OLC probably does not want to weigh in on). This affirmative repudiation of the basis of the policy prevents future executive branches–in theory at least–from relying on this past practice. As we learned in Noel Canning, the Court is extremely deferential to the internal practices of the executive branch–what Justice Scalia called in his concurring opinion an “adverse possession” theory of executive power. The executive should not be able to suspend the law under the bogus guise of prosecutorial discretion. And lest DAPA supporters think this is a bad idea, I would hope such a clearly-stated policy in the early days of a Trump administration binds President Trump himself in the future.

Title IX Litigation

Currently, there are several cases pending throughout the federal judiciary concerning the import of the Department of Education’s “Dear Colleague” letter interpreting Title IX prohibition of “sex” discrimination to also include a prohibition on “gender identity” discrimination. The Court has already granted certiorari on Gloucester County School Board v. GG with respect to second and third questions:

2. If Auer is retained, should deference extend to an unpublished agency letter that, among other things, does not carry the force of law and was adopted in the context of the very dispute in which deference is sought?

3. With or without deference to the agency, should the Department’s specific interpretation of Title IX and 34 C.F.R. § 106.33 be given effect?

Another suit, brought by the Texas, facially challenged the legality of the “Dear Colleague” letter. In contrast, in GG a student claimed discrimination on the basis of gender identity, and cited the “Dear Colleague” letter as a basis for the case, but not the sole basis. The pressing variable is whether the Trump Administration withdraws the “Dear Colleague” letter. If it does, Texas’s case automatically goes away, but GG’s does not–question 3 still remains available for resolution.

At that point, the Court would have a few options.

First, the petition can be DIG’d. The Court doesn’t need to give a reason for the DIG, but the import would be that indeed the grant was improvident in light of the government’s changed position. Critically, a DIG would leave the Fourth Circuit’s opinion in effect–although this would be strange, because the Fourth Circuit’s decision was premised entirely on Auer grounds. Circuit precedent would then be based on an opinion that was no longer valid. As I understand it, GG is about to graduate, but still seeks to use facilities in the school district for alumni events. A DIG would also provide further protection for GG with respect to facilities in Gloucester County schools, but nowhere else.

Second, the petition can be vacated and remanded in light of the withdrawal of the “Dear Colleague” letter. This could be a one-sentence order, and no explanation needs to be given–although it could be accompanied by a (Sotomayor) dissent. Formally, the remand would make sense to allow the lower court to consider in the first instance if GG’s interpretation of Title IX prevails de novo. Maintaining a circuit precedent based on a withdrawn opinion cannot be correct. Informally, this would buy the Court some time to have the case argued with a full bench.

Third, the Court can go ahead an argue the case. I’ve heard that the Court wanted this case argued in February–at that point, a new Justice will almost certainly have been nominated, but not yet confirmed. There is no requirement to delay the argument until a ninth Justice is confirmed. In the event that it is argued, and there are (at least) five votes for a majority opinion, it can be resolved with eight. But if the case is split four-to-four, it would be necessary to reargue the case.

In recent years, virtually all new Justices have been confirmed before the first Monday in October, so it has not been necessary to deal with the problem of a Justice confirmed in the middle of the term. But, as I understand the practice, in order for the new Justice to vote on the case, it will have to be reargued. That is, a newly confirmed Justices cannot simply review the transcript of a case argued before the confirmation. There are two examples in recent history that come to mind. First, in late 2005–at which point Justice Alito was nominated, but not yet confirmed–three cases were argued where Justice O’Connor would have cast the tie-breaking vote. (Hudson v. Michigan, Kansas v. Marsh, and Garcetti v. Ceballos). After Justice Alito was confirmed in January 2006, each of those cases were re-argued, and Alito cast the fifth vote in each. It wasn’t enough to have Alito simply read the transcript from the first argument. Fifteen years earlier, Justice Thomas did not assume office until October 23, 1991. By that point, 20 cases had been argued. (The court heard so many more cases back then!). Thomas would have only cast the tie-breaking vote in one of those cases–Doggett v. United States–so it was reargued in February 1992.

Here come’s the rampant speculation, which you are free to disregard. That the Justices granted certiorari on this case suggests that either (a) there were five votes for ruling on question 2 or 3, or (b) that they anticipated a new Justice would be confirmed before the case is decided. I am doubtful that it is the latter, in light of the fact that Trinity Lutheran remains in docket purgatory. The Justices seem hesitant to schedule any cases that is likely to split 4-4. Therefore, there could have been five votes to rule on this case as granted. On what grounds, we do not know: Question 2 or Question 3. If there were only five votes to rule for GG on Question 2–if the “Dear Colleague” letter is withdrawn–those five votes go away. If there were five votes to rule for GG on Question 3, those five votes would still remain. As I predicted, and Mike Dorf was on the same wavelength, this case may be resolved entirely on Question 3.

However, the Trump Administration could take proactive steps to nudge the Court towards a remand, rather than arguing it now. Consistent with my comments above, it is not enough to simply withdraw the “Dear Colleague” letter. Doing so would reflect a mere policy reversal. A stronger technique would be a legal opinion stating that reinterpreting the phrase “sex” in Title IX in such a significant change that must be address through the notice-and-comment process, and it cannot be accomplished by a single letter.

This option has several benefits. First, it would, or at least should, give the five votes on the Court pause to think that de novo, this is the best interpretation of Title IX. Remember, once we are no longer in Auer land, it is not enough for the interpretation to be “reasonable.” If indeed the “Dear Colleague” created a profound change in longstanding policy, that by itself suggests that under de novo review, GG loses. Second, it would establish an official position within the Administration that policy cannot be changed through what I’ve referred to as “Regulation by Blog Post.” Process matters. The new approach could be dubbed “Deregulation by Blog Post.” As I noted above, setting benchmarks for limits on President Trump’s authority should be desirable by even those who support GG”s appeal. I sincerely hope conservatives do not drop their opposition to Auer deference now that there is a new sheriff in town. Finally, it would withdraw the memo without taking a substantive position on a serious culture war issue. Explaining that the Letter was unlawful to effect a change in policy is quite different than arguing that Title IX permits discrimination on the basis of gender identity. MSNBC may not care about the difference, but it is significant for courts.

In short, I think the best options would be to remand the case to the Fourth Circuit. Or the Court can simply decline to calendar the case–as they did with Trinity Lutheran–until a ninth member is confirmed. Scheduling it for argument in February, only to receive a letter from the Solicitor General on January 20 about the withdrawal of the “Dear Colleague” letter, would waste a lot of time and preparation efforts. The tenor of the argument changes radically depending on whether the question 2 is in play. Better choice: hang tight till everything settles.

More generally, I hope the Court considers adding a May, and possibly even a June sitting, to ensure that as many cases as possible are decided with a full bench. (I made this point in an interview with Kimberly Robinson on Bloomberg BNA in July). Also, there’s no requirement to rush to the finish on the last Tuesday in June–Justice Kennedy may wish to postpone his trip to Salzburg another year.

Zubik v. Burwell

The ongoing contraceptive mandate cases can also be removed from the docket, but the framework would be complicated. As I discuss in Unraveled and my new Harvard Law Review comment, the remand in Zubik v. Burwell was far more contested than the Court made it seem.

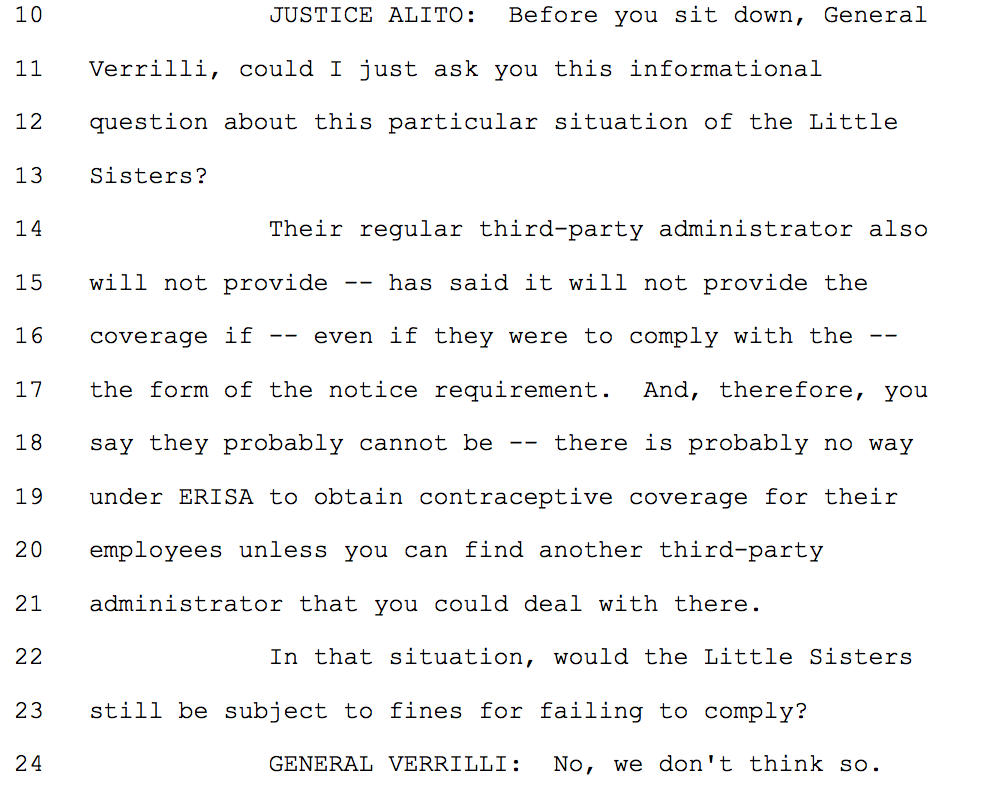

First, for employers with “Church Plans,” such as the Little Sisters of the Poor, the government conceded that they could not be fined for non-compliance. This exchange between Justice Alito and SG Verrilli explains the dynamics quite well:

Yet, even though the Little Sisters cannot be fined, the government is still requiring them to submit a signed document–whether a letter or EBSA Form 700. This never made sense to me: why make them sign a document under protest that will in no way result in female employees receiving contraception coverage. To resolve the issue of employers with Church Plans, the government can issue a rulemaking that says something to the effect of, “In light of the fact that the government lacks the ability to penalize the employers with church plans, we will simply exempt such plans from the contraceptive mandate.” Call it the futility doctrine. This would put religious charities with church plans in the exact same boat as houses of worship with church plans–the latter are already exempted from the mandate. As it stands now, the female employees of the Little Sisters do not have access to contraception on their church-plans. Such a rulemaking would maintain that status quo, and absolve the Little Sisters from filling out a frivolous form they deem sinful. Of course, the government remains free to pay another third-party provider to offer contraception coverage–as Justice Alito suggested.

Second, a similar resolution applies for self-insured plans. Through a self-insured plan, the employer acts as its own insurer and assumes financial responsibility for its employees’ health care claims. To reduce the administrative burdens, these employers will contract with a third-party administrator, who will manage the administration of the plan. As the government conceded in its supplemental brief ERISA does not authorize the government to require the third-party administrator to provide payments independent of the employer’s plan. In effect, insurers cannot provide contraception coverage to the female employees on a self-insured plan unless the employer executes the instrument that creates the new legal obligation. Neither the government nor the challengers were able to figure out a way to resolve this legal dispute in the Zubik supplemental briefing. A similar rulemaking should be applied to self-insured plans, as apply to Church Plans: “To avoid the substantial burden on the free exercise of employers with self-insured plans, and in light of the fact that a less-restrictive means exist to serve the government’s interest, we will simply exempt such plans from the contraceptive mandate.” As noted above, the government remains free to pay another third-party provider to offer contraception coverage.

Third, for insured plans, the resolution is the simplest. With an insured plan, the employer purchases a group plan from a health insurer, such as Aetna. Aetna then manages all aspects of the group plan. The Affordable Care Act and its implementing regulations require Aetna to make payments for contraception coverage. If a religious employer notifies the government that it objects to the mandate and wants the accommodation, Aetna must provide contraceptive payments separately from the employer’s insured plan. In their order, the justices proposed that employers with insured plans would no longer need to object in the manner specified by the regulations. Instead, they might simply “inform their insurance company that they do not want their health plan to include contraceptive coverage of the type to which they object on religious grounds.” Once the insurance company is “aware that petitioners are not providing certain certain contraceptive coverage on religious grounds,” the same insurer can provide contraceptive payments directly to the employees.

In its supplemental brief, the solicitor general wrote that this modified accommodation would work “for employers with insured plans … while still ensuring that the affected affected women receive contraceptive coverage seamlessly, together with the rest of their health coverage.” The challengers mostly agreed that with respect to insured plans, their religious exercise is not infringed where they “need to do nothing more than contract for a plan that does not include coverage for some or all forms of contraception.” But there was a critical distinction. This approach would be acceptable for the nonprofits so long as contraceptive payments were made pursuant to a totally “separate plan,” and only if the women were required to opt in to such a new insurance policy before seeking any reimbursements. To resolve this conflict, a rulemaking should provide that for insured plans, contraception can only be paid for through a separate plan.

Currently, the government sought additional comments following Zubik. A response is due to the courts on November 30. That deadline should be extended, and the new administration should simply seek comments along the lines I discussed above.

Critically, these two solutions would apply not only to non-profit religious charities, but also for-profit employers with self-insured plans that profess bona fide religious objections to the mandate. As this article in Politico noted last month, the universe of objecting employers is fairly finite–most of them are involved in the litigation.

Since the 2014 high court ruling in favor of Hobby Lobby, only 52 companies or nonprofit organizations, have told the government they plan to opt out of Obamacare’s requirement to cover birth control because it violates their religious beliefs, according to a POLITICO review of Obama administration records obtained under the Freedom of Information Act.

That’s in addition to the employers who filed about 100 lawsuits against the contraception mandate, as well as an unknown number of employers that may have directly informed their insurer, instead of the government, of their religious objections — a tack taken, for example, by Georgetown University, a Catholic institution that offers insurance to students and employees.

…

“If that is anywhere close to the universe of entities [that object to the contraception mandate], that it is a little surprising,” said Tim Jost, a legal expert on the health law and a member of the Institute of Medicine.

This should not be an open-ended problem. Admittedly, this approach is not “seamless” and imposes a greater burden on female employees. Had Congress actually bothered to define how this provision would work, the President would be constrained. However, because Senator Mikulski–who sponsored the Women’s Health Amendment–was content to give the Obama Administration carte blanche to figure out the details, that same power now devolves to the Trump Administration. Broad delegations cut both ways. I’ve argued at some length that the accommodation system developed by the Obama Administration–where it decides that some religious groups are exempt, but other less-religious groups are non-exempt–is entirely ultra vires. The solutions I sketched out above would not suffer from that problem. Rather, (1) employers with church plans are not required to sign a futile form, (2) employers with self-insured plans are not compelled to amend their plans to do something they deem sinful, and (3) insured plans can be tweaked to provide coverage with far more ease.