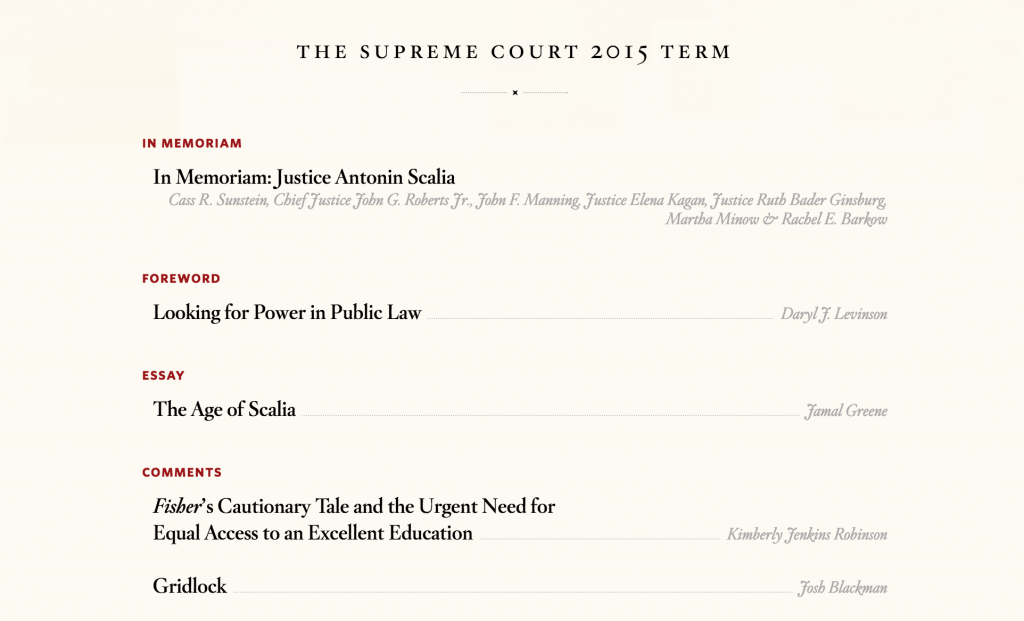

Today the Harvard Law Review released its issue on the Supreme Court 2015 Term. The issue, dedicated to Justice Scalia, includes entries from authors such as Chief Justice Roberts, Justice Ginsburg, Justice Kagan, and … me! Looking at the cover page reminds me of the Sesame Street song, “One of these things is not like the other.” My entry, Gridlock, discusses U.S. v. Texas and Zubik v. Burwell.

Here is the introduction:

Two of the biggest cases at the Supreme Court this past term ended as they began: gridlocked. In Zubik v. Burwell, the Justices declined to decide the validity of the accommodation to the Affordable Care Act (ACA) contraceptive mandate. In United States v. Texas, the Court divided 4–4 on whether Deferred Action for Parents of Americans (DAPA) was lawful.

Both cases involved extremely delicate line drawing. In the former, the Justices had to determine whether compliance with the accommodation to the contraceptive mandate imposed a substantial burden on the free exercise of religious organizations. In the latter, the Court was called on to resolve the scope of the President’s prosecutorial discretion to shield from removal and grant lawful presence to nearly four million aliens. During oral argument — our only source of insights because neither case generated a decision on the merits — the Justices seemed divided on how to balance powerful competing concerns. In the end, the Court resolved neither case — at least for now.

The eight Justices can be forgiven for not being able to reach a clear decision. Congress, and not the courts, should lead the debates over such profound questions about religious liberty and the separation of powers. Indeed, critics allege that both suits are actually policy disputes masquerading as legal controversies. But these suits arose precisely because Congress did not grapple with these foundational issues. Congress was entirely silent about religious accommodations for the contraceptive mandate, and Congress affirmatively rejected a change to the immigration status quo. Consequently, the Administration seized on this inaction to justify executive actions that advanced an expansive change in policy.

To establish an elaborate scheme that picks and chooses which religious groups are exempted from the contraception mandate, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) cited its authority to define what should constitute “preventive care.” To effect a fundamental change in immigration policy, DAPA relied on two statutes that authorize the Secretary of Homeland Security to “[e]stablish[] national immigration enforcement policies and priorities” and to “perform such other acts as he deems necessary.” In both cases, the executive branch relied on anodyne delegations of authority to resolve profound questions of social, economic, and political significance — questions the legislature would not cryptically assign to the executive branch. Indeed, such polarizing bills could never have been enacted in the first instance in our current political climate. The five-page per curiam decision in Zubikand the one-sentence affirmance in Texas are the judicial fallout from our gridlocked government.

As Congress becomes more polarized, it becomes less able to resolve major questions affecting social, economic, and political issues. With his legislative agenda frustrated, the President takes executive action on those questions Congress either ignored or rejected by adding expansive glosses to generic delegations of authority. The courts are then called upon to assess whether the line the executive drew was within his delegated authority. But these disputes can be resolved on the more neutral principle of whether the agency can take such novel actions in the first instance. If the answer is no, there is no need for judges to draw that difficult line. These “major questions” should be returned to the political process — which is where they should have been decided to begin with.

My goal in this Comment is not to explain whether DAPA complies with the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), or whether the contraception mandate’s accommodation violates the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (RFRA). In fairness, the Court didn’t either. (Texas and Zubik — combined, only ten slip pages — are likely the shortest corpus ever for a faculty comment in the Harvard Law Review’s annual Supreme Court issue.) Rather, I use these two cases to illustrate the relationship between gridlocked government and the separation of powers. Part I applies this framework to Zubik v. Burwell to demonstrate why congressional silence does not vest the executive branch with the awesome authority to make foundational determinations affecting conscience. Part II analyzes United States v. Texas to explain how congressional gridlock does not license the expansion of the executive’s authority. I conclude with a preview of how these cases are likely to be resolved on remand.

Although in light of the election returns, Part III is now moot. As I discuss this morning in National Review, both Texas and Zubik will soon draw to a close due to changed administrative positions.

I am grateful to Josh Chafetz who wrote a thoughtful reply, fittingly titled Gridlock? HLR should include at least two Joshs in every issue.