Since I published The Shooting Cycle in 2014, I have told anyone who would listen that mass shootings and so-called “assault weapons” make up only a tiny fraction of gun violence in the United States, and should not form the basis of our gun control policy. Rather, handgun violence in inner-city, mostly minority neighborhoods, makes up the overwhelming majority of gun deaths.

The Guardian (UK) offers a strikingly sober take on these two critical issues.

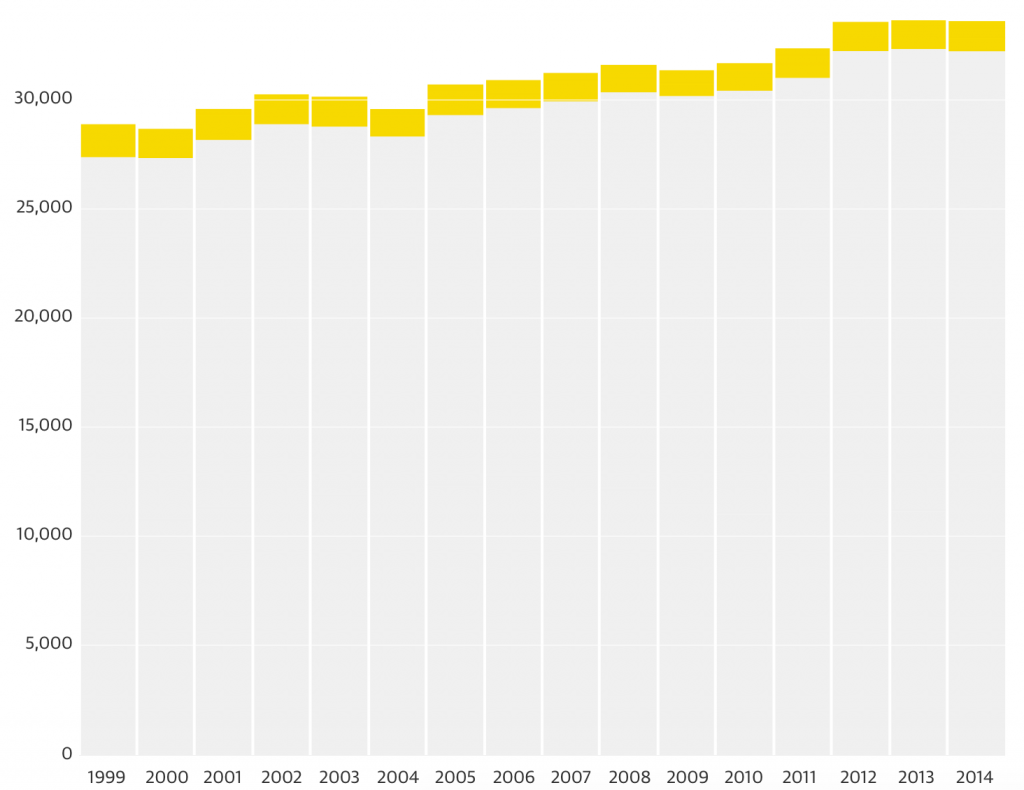

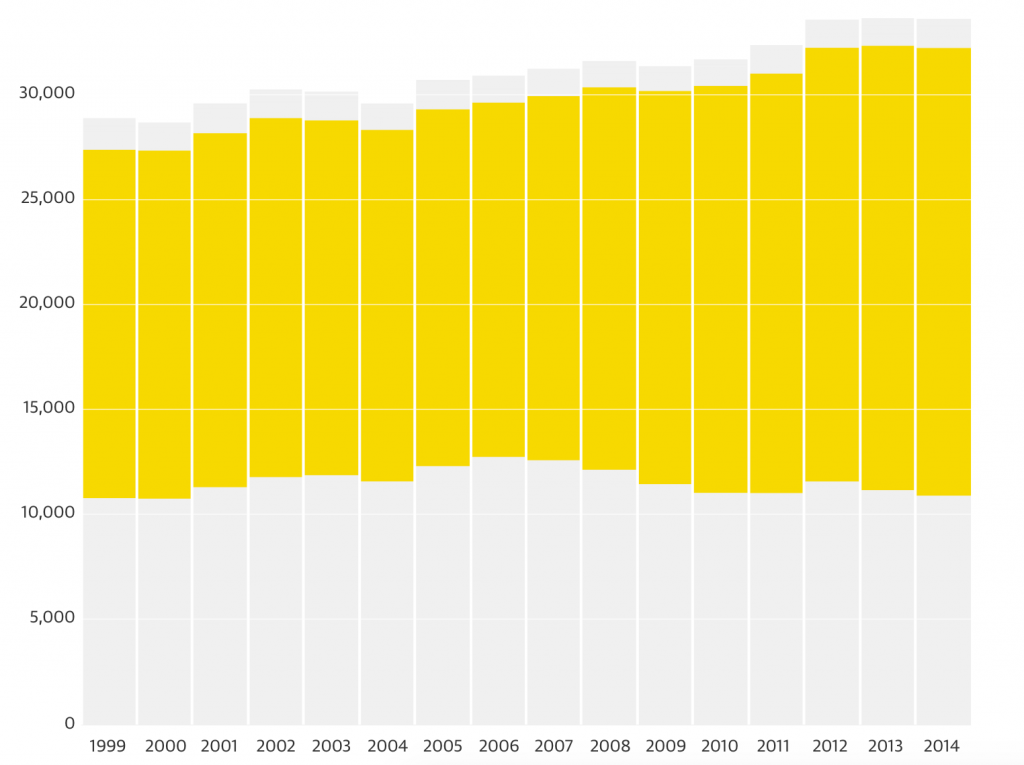

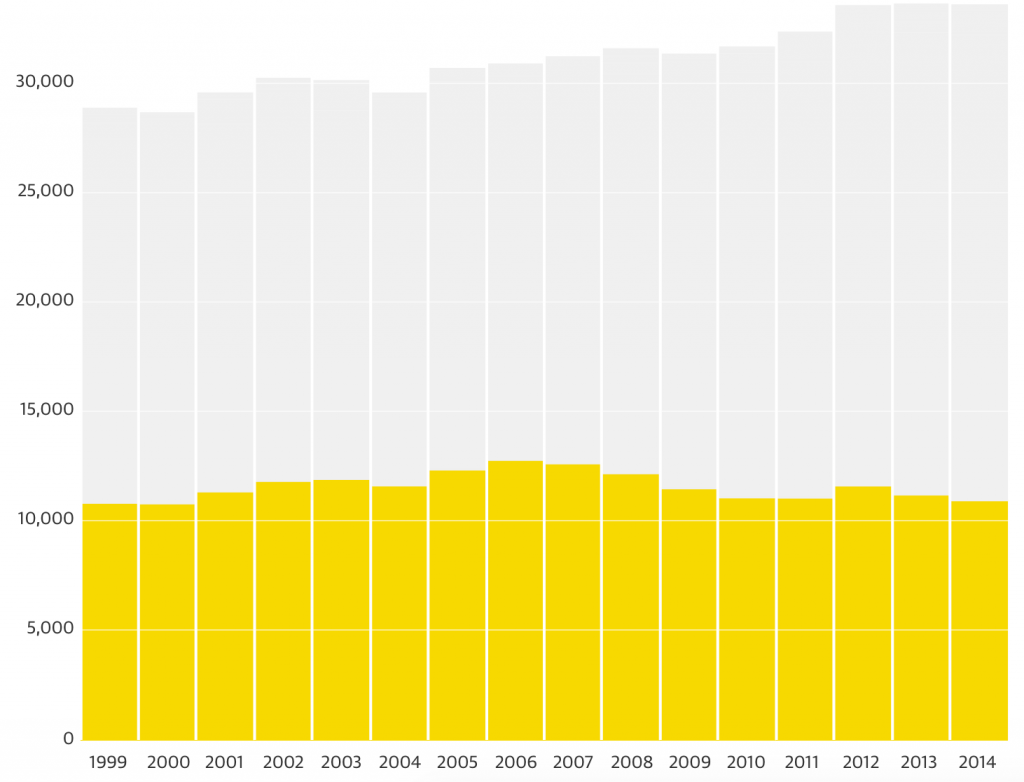

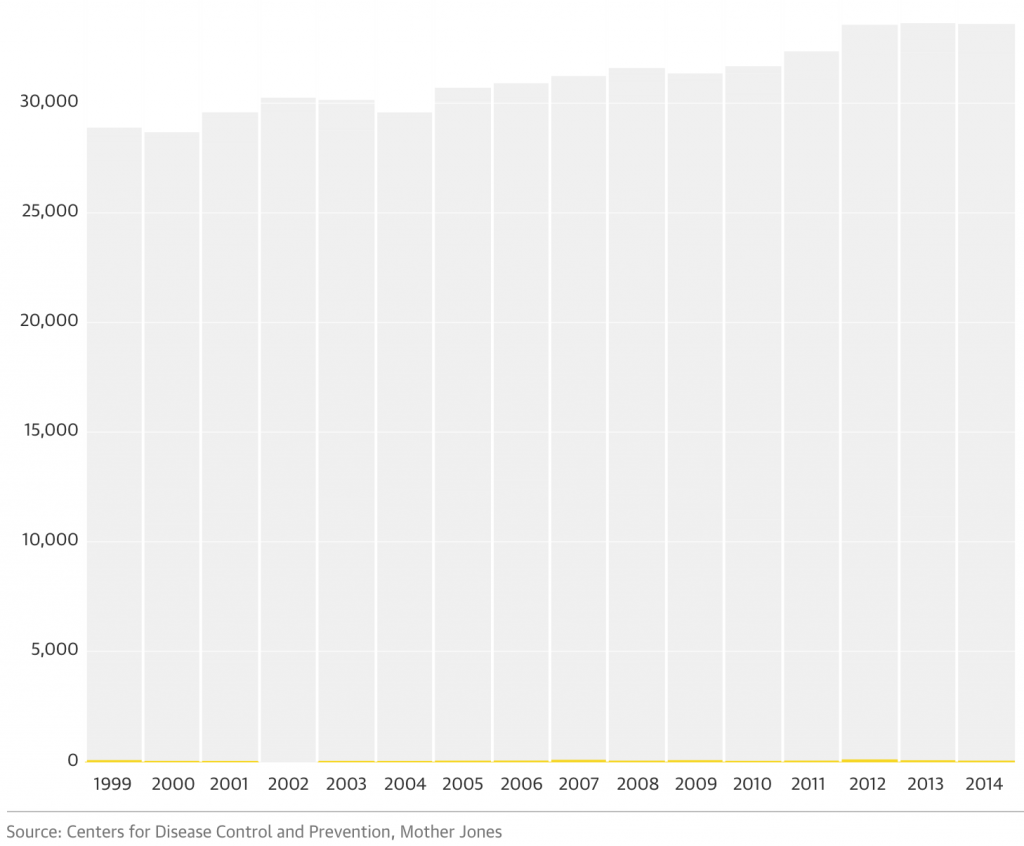

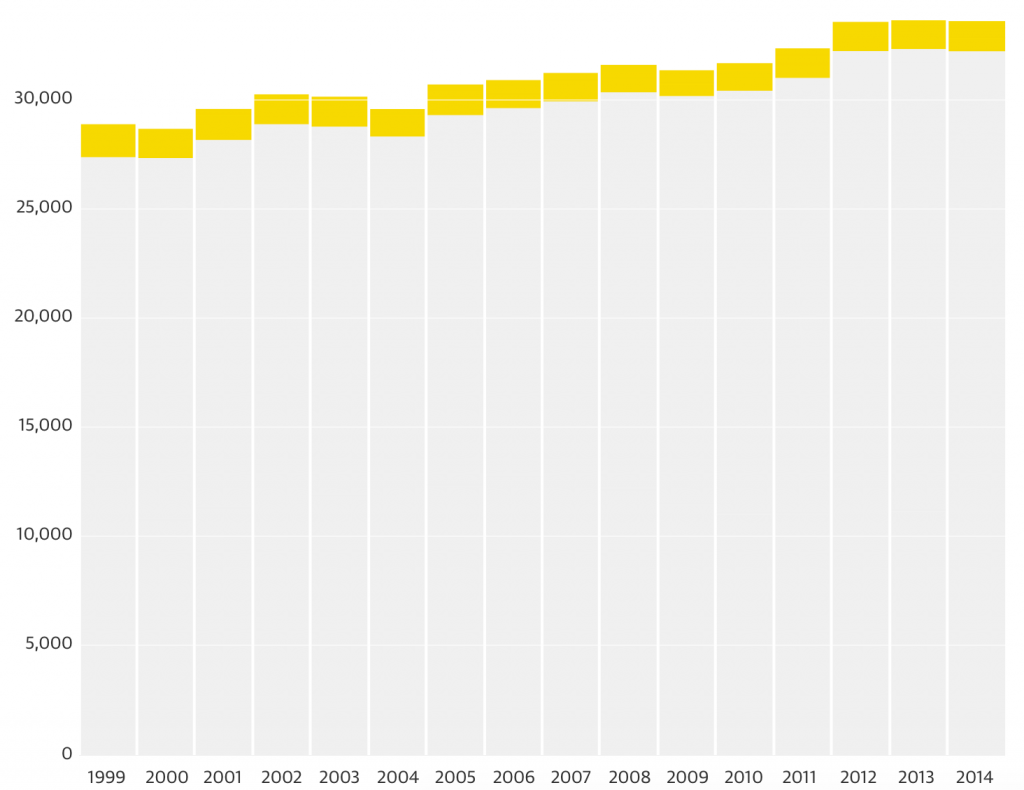

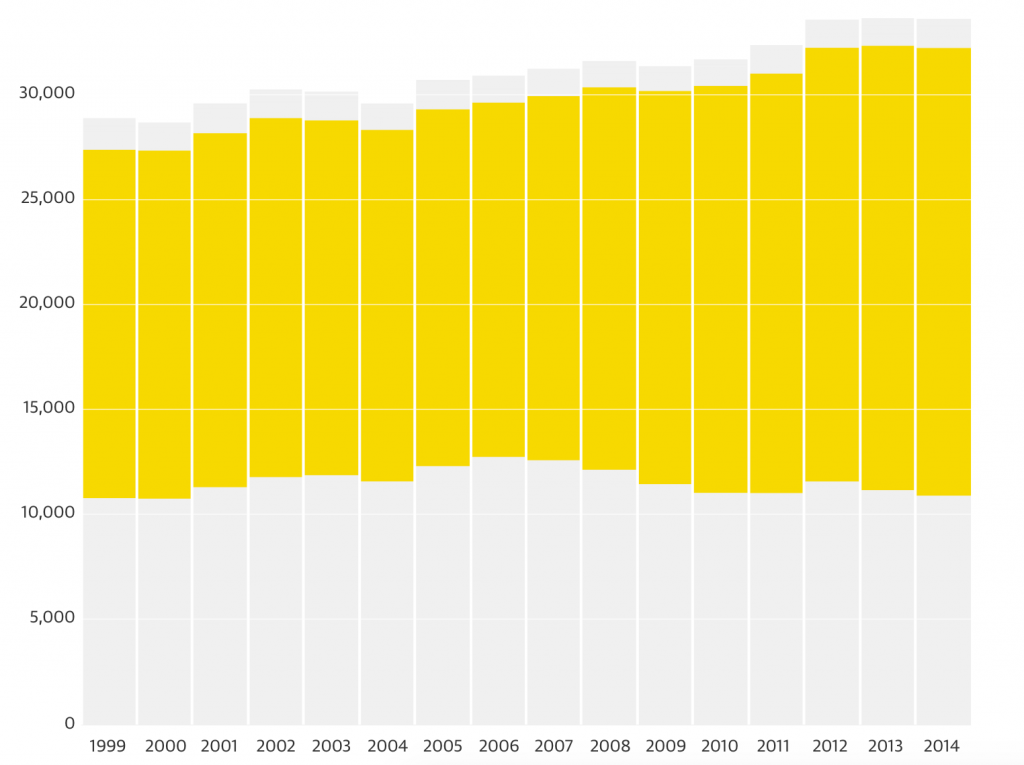

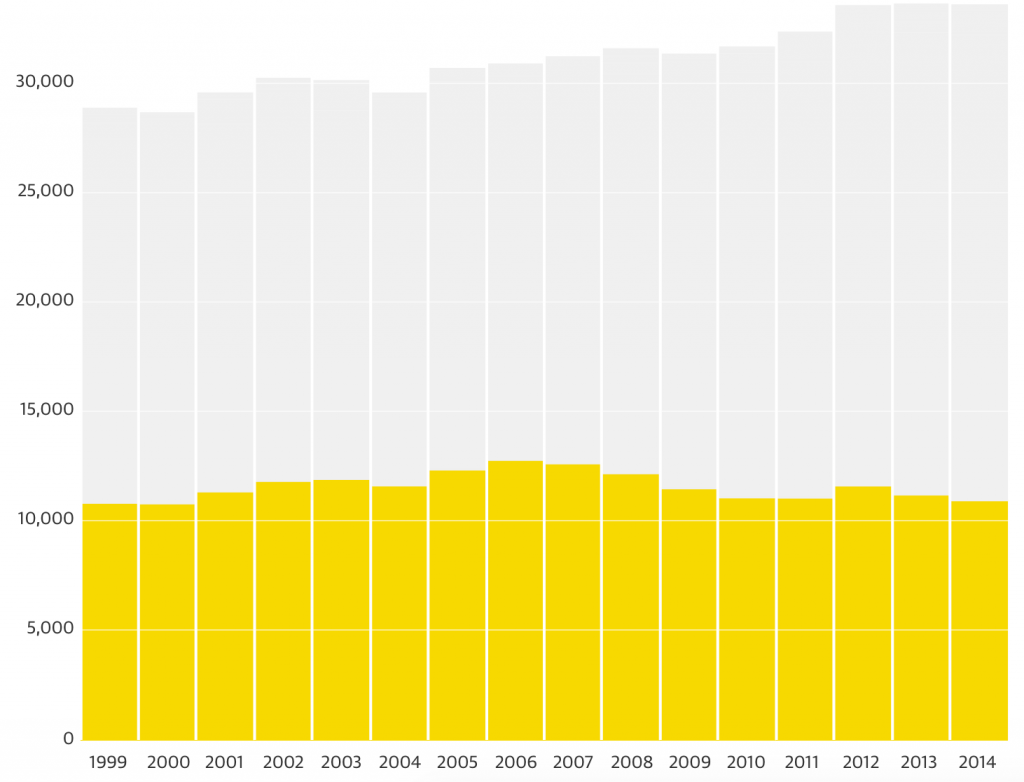

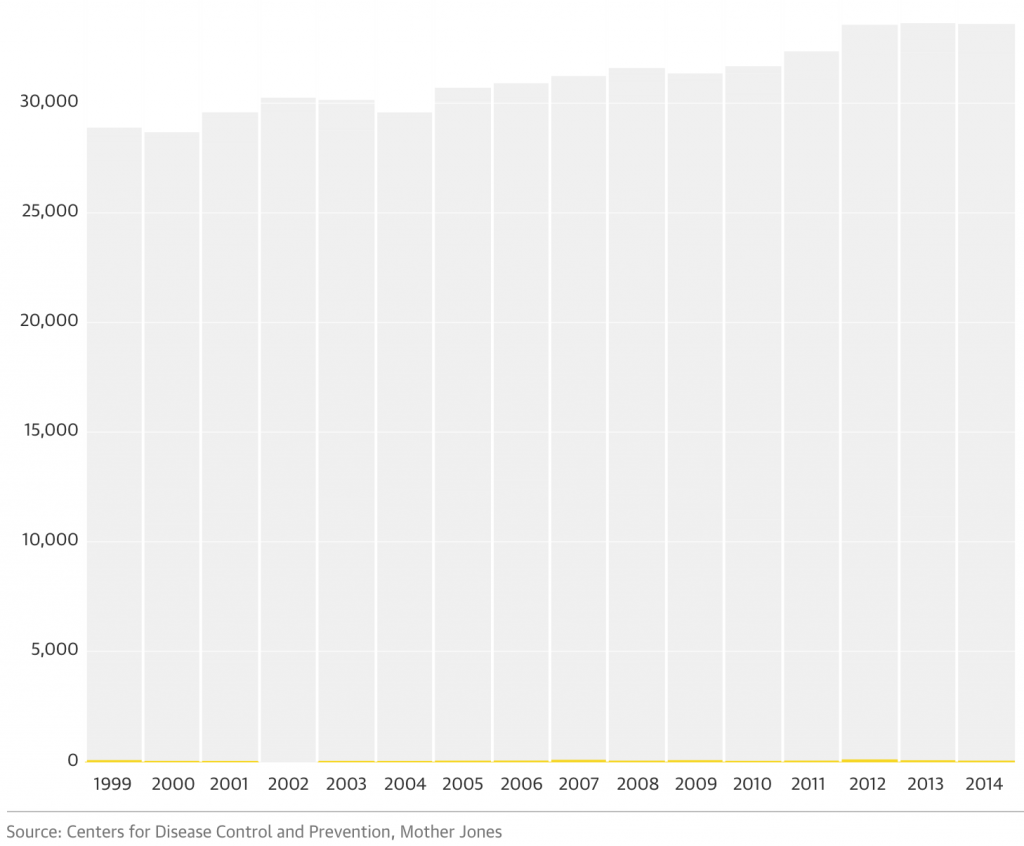

First, mass shootings constitute an extremely, extremely small sliver of gun deaths. Each year, on average, about 33,500 people are killed by a firearm. That is roughly the same rate as death by car accidents.

The CDC categorizes 4% as “unintentional,” “legal intervention” (shot by a cop), or some other undetermined cause.

The over-whelming majority–over 60%–are death-by-suicide.

The remainder, about 11,000 per year, are homicides.

Of those, only a small sliver could count as mass shootings. The Guardian relies on Mothers Jones’s database, which uses a broader definition of mass shooting than the federal government does; I won’t quibble here, because even using a broad definition, the number of mass shootings as compared to the total number of other gun deaths is still extremely tiny. On the graph, you can barely even make out the yellow slivers at the bottom.

The Guardian concludes:

But next to the thousands of lives lost each year to suicide and more commonplace acts of violence, it becomes clear that mass shootings are only a tiny part of America’s gun problem. The US could end all mass shootings today and its rates of gun violence would still be many times higher than other rich countries.

This is exactly right.

Second, mass shootings attract a disproportionate share of attention, even as the disproportionate share of violence falls on minority, inner-city communities. Compare the reactions to 49 deaths in Orlando last month to the 71 people who were murdered in Chicago during the month of June (6o of whom were black). Elites tend only to react to gun deaths when they think it can affect them: who cares about inner cities, but if it is a gay night club or a kindergarten, we must take action!

The Guardian observes:

African Americans, who represent 13% of the total population, make up more than half of overall gun murder victims. Roughly 15 of the 30 Americans murdered with guns each day are black men. . . .

Because everyday gun violence is concentrated in racially segregated neighborhoods, it’s easy for millions of Americans to think they won’t be affected.

“As soon as it’s anybody’s kindergartener that can be at risk, we’re a hell of a lot more terrified, because there is no social class or geographic address that makes one exempt,” Zimring said.

…

A debate conducted in the aftermath of mass shootings has also prompted a huge public investment in guarding and fortifying public schools against shootings, even though the typical school can expect to see a student homicide only once every 6,000 years, according to safety expert Dewey Cornell.

Since the 1999 school shooting at Columbine high school in Colorado, the justice department has invested nearly $1bn to help put police officers in schools, though Cornell notes there is still little evidence that school security measures reduce crime.

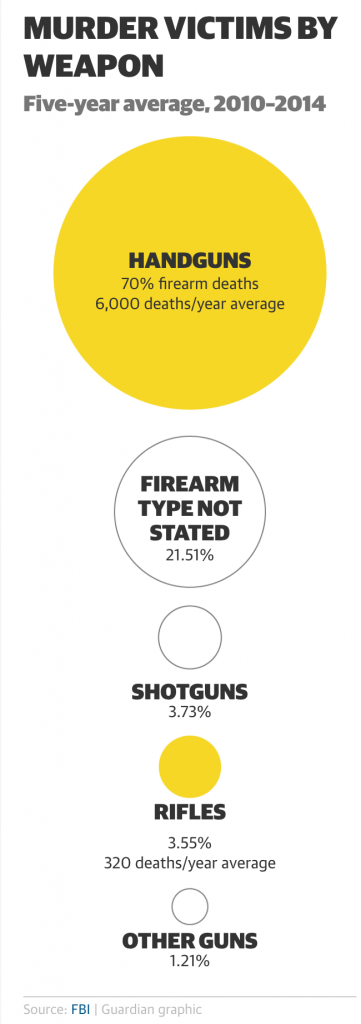

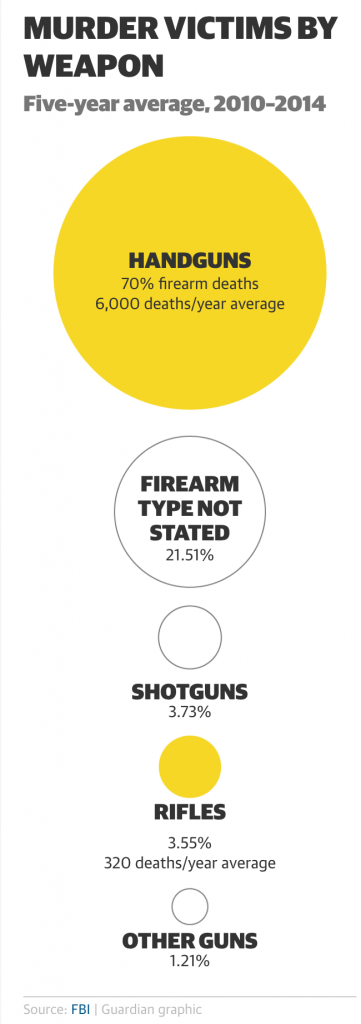

Third, the focus on the AR-15 and so-called “assault weapons” is completely misplaced. The overwhelming amount of gun violence is caused by simple handguns. Rifles constitute less than a 4% share of murders. Shotguns–the weapon Joe Biden recommended Americans use to defend themselves–are involved in more murders.

The New York Times in September 2014 (before their front page editorial) also recognized the myths about assault weapons.

But in the 10 years since the previous ban lapsed, even gun control advocates acknowledge a larger truth: The law that barred the sale of assault weapons from 1994 to 2004 made little difference.

It turns out that big, scary military rifles don’t kill the vast majority of the 11,000 Americans murdered with guns each year. Little handguns do.

In 2012, only 322 people were murdered with any kind of rifle, F.B.I. data shows.

Not too long ago, gun controllers were quite open about their goal of banning all handguns. Nelson “Pete” Shields III, a founder of Handgun Control, Inc.—the aptly named progenitor of the Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence—openly advocated for the elimination of all handguns:

‘We’re going to have to take this one step at a time. . . . Our ultimate goal—total control of all guns—is going to take time.’ The ‘final problem,’ he insisted, ‘is to make the possession of all handguns and all handgun ammunition’ for ordinary civilians ‘totally illegal.’

John Hechinger, a sponsor of the Washington, D.C., handgun ban and a board member of Handgun Control, Inc., put it simply: “We have to do away with the guns.” The same can be said for Michael Bloomberg’s group, Mayor Against Illegal Guns, which has as its ultimate goal confiscation of handguns.

Realizing that this is not a viable option they have instead focused on eliminating scary-looking guns (AR-15), with a scary sounding titles (“assault weapon”), which have a strikingly small impact on actual gun deaths. Why? To stigmatize firearms altogether, and make it easier to confiscate handguns later.

Conservative columnist Charles Krauthammer accurately summarized the reasoning for these measures in 1996. He argued that the assault weapons ban would not result in a decrease in violence, but would serve as an important symbolic step down the path to banning all guns by desensitizing Americans to gun control laws. Krauthammer stated:

Ultimately, a civilized society must disarm its citizenry if it is to have a modicum of domestic tranquility of the kind enjoyed in sister democracies like Canada and Britain. Given the frontier history and individualist ideology of the United States, however, this will not come easily. It certainly cannot be done radically. It will probably take one, maybe two generations. It might be 50 years before the United States gets to where Britain is today.

Passing a law like the assault weapons ban is a symbolic— purely symbolic—move in that direction. Its only real justification is not to reduce crime but to desensitize the public to the regulation of weapons in preparation for their ultimate confiscation. Its purpose is to spark debate, highlight the issue, make the case that the arms race between criminals and citizens is as dangerous as it is pointless.

De-escalation begins with a change in mentality. And that change in mentality starts with the symbolic yielding of certain types of weapons. The real steps, like the banning of handguns, will never occur unless this one is taken first, and even then not for decades.

My conclusion from The Shooting Cycle still holds:

The way to accomplish this cultural shift of reversing the trend line is not through flaming fears following mass shootings, and trying to pass through the backdoor proposals that people did not want before. This makes gun owners not trust gun controllers—with good reason. As Professor Winkler noted, “Many gun owners might have supported background checks had they not been distracted by the assault weapons issue, which caused them to distrust gun control proponents even more than before.” Why should they? Every time there is a tragedy and support for background checks is strong, gun controllers aim high and try to reintroduce failed gun-control bills. Professor Winkler reminds us that the ultimate aim of “disarmament is an unrealistic goal.” The fact that “[g]uns are permanent in America” is “perhaps the most important” fact that the “gun ban supporters failed to grasp.” As long as this fear persists, and remains the obvious end-goal of these groups, the NRA’s fanning the flames of confiscation remains viable.