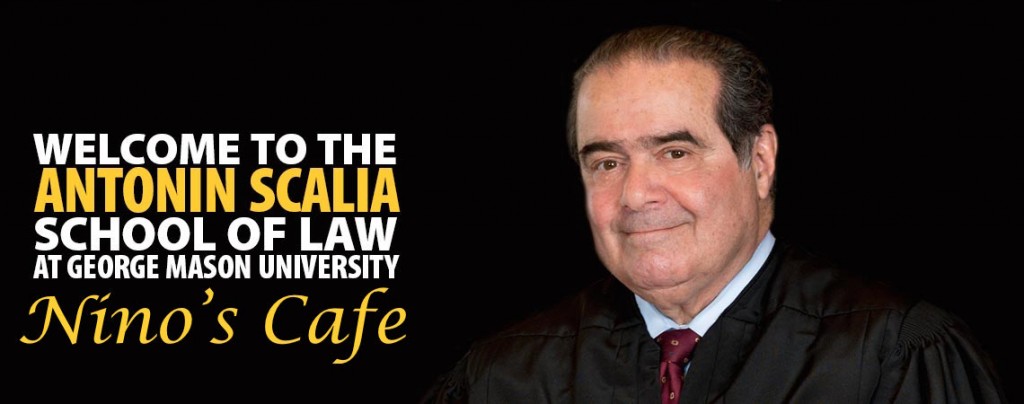

Justice Scalia, who lived half of his life in northern Virginia, opined on the Commonwealth’s universities in the U.S. Reports. In United States v. Virginia, which considered the constitutionality of the Virginia Military Institute’s all-male program, Justice Scalia’s dissent weighed in on how Universities in Virginia–including George Mason–structure their policies to attract different types of students.

Finally, the Court unreasonably suggests that there is some pretext in Virginia’s reliance upon decentralized decisionmaking to achieve diversity-its granting of substantial autonomy to each institution with regard to student-body composition and other matters, see 766 F. Supp., at 1419. The Court adopts the suggestion of the Court of Appeals that it is not possible for “one institution with autonomy, but with no authority over any other state institution, [to] give effect to a state policy of diversity among institutions.” Ante, at 22 (internal quotation marks omitted). If it were impossible for individual human beings (or groups of human beings) to act autonomously in effective pursuit of a common goal, the game of soccer would not exist. And where the goal is diversity in a free market for services, that tends to be achieved even by autonomous actors who act out of entirely selfish interests and make no effort to cooperate. Each Virginia institution, that is to say, has a natural incentive to make itself distinctive in order to attract a particular segment of student applicants. And of course none of the institutions is entirely autonomous; if and when the legislature decides that a particular school is not well serving the interest of diversity-if it decides, for example, that a men’s school is not much needed-funding will cease. 26

[ Footnote 26 ] The Court, unfamiliar with the Commonwealth’s policy of diverse and independent institutions, and in any event careless of state and local traditions, must be forgiven by Virginians for quoting a reference to “the Charlottesville campus” of the University of Virginia. See ante, at 20. The University of Virginia, an institution even older than VMI, though not as old as another of the Commonwealth’s universities, the College of William and Mary, occupies the portion of Charlottesville known, not as the “campus,” but as “the grounds.” More importantly, even if it were a “campus,” there would be no need to specify “the Charlottesville campus,” as one might refer to the Bloomington or Indianapolis campus of Indiana University. Unlike university systems with which the Court is perhaps more familiar, such as those in New York (e.g., the State University of New York at Binghamton or Buffalo), Illinois (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign or at Chicago), and California (University of California, Los Angeles or University of California, Berkeley), there is only one University of Virginia. It happens (because Thomas Jefferson lived near there) to be located at Charlottesville. To many Virginians it is known, simply, as “the University,” which suffices to distinguish it from the Commonwealth’s other institutions offering four-year college instruction, which include Christopher Newport College, Clinch Valley College, the College of William and Mary, George Mason University, James Madison University, Longwood College, Mary Washington University, Norfolk State University, Old Dominion University, Radford University, Virginia Commonwealth University, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Virginia State University-and, of course, the Virginia Military Institute.

Of course, Footnote 26 was occasioned by Justice Ginsburg, whose first draft referred to UVA as “the University of Virginia at Charlottesville.” Of course, no such place exists.

Scalia and Ginsburg reminisced about this exchange during a February 2015 event at GW:

The back-to-back banter illustrated good humor rather than genuine disputes. Justice Scalia recalled the 1996 case when the Supreme Court struck down the Virginia Military Institute’s male-only admissions policy. In the decision, Justice Ginsburg mistakenly referred to “The University of Virginia at Charlottesville” in a footnote, an error Justice Scalia was quick to point out.She fixed the missive not by changing the name of the school, but by quoting another judge who had referred to the university in the same way.“She knew it was wrong, but she was too proud to change it,” Justice Scalia remembered, crossing his arms in a pantomime of annoyance.

Also, Scalia’s comment that “Unlike university systems with which the Court is perhaps more familiar”–such as in Illinois, New York, or California–evokes his critique in Obergefell that the bulk of the Justices are from the coasts.

Take, for example, this Court, which consists of only nine men and women, all of them successful lawyers who studied at Harvard or Yale Law School. Four of the nine are natives of New York City. Eight of them grew up in east- and west-coast States. Only one hails from the vast expanse in-between. Not a single South- westerner or even, to tell the truth, a genuine Westerner (California does not count).