The lecture notes are here.

Individual Liberty I

- Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1476-1478).

- Buck v. Bell (1428-1432).

- Griswold v. Connecticut (1478-1494).

Pierce v. Society of Sisters

This is the Hill Military Academy, a private school shut down due to the compulsory education law.

Buck v. Bell

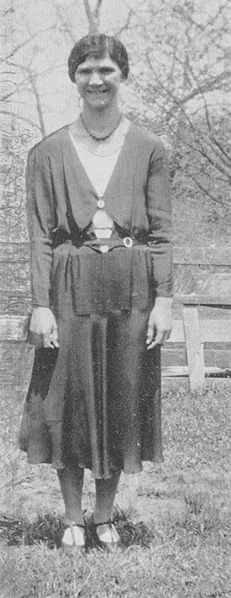

This is Carrie Buck. Why was she designated as “feebleminded”? Because she had an “illegitimate child,” and they charged her with “promiscuity.” The pregnancy resulted from a rape.

This is Carrie Buck with her mother, Emma Buck.

This is Dr. J. H. Bell, the superintendent at the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics.

This is the courthouse in Amherst County, Virginia where Buck’s case was first “heard”:

This is the “State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded,” where Carrie Buck was sterilized in the wake of Buck v. Bell.

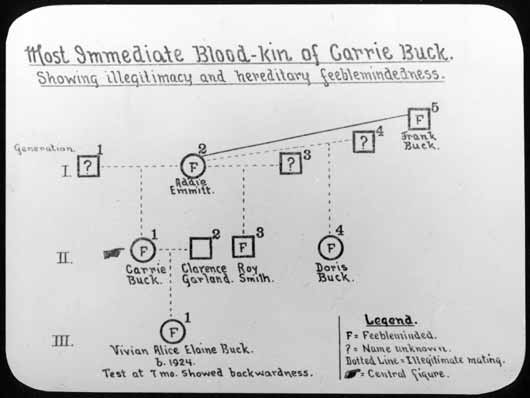

Here is a rendering of Carrie’s Buck family tree, as performed by Dr. Harry H. Laughlin. F stands for “feebleminded.” Notice That Carrie Buck is designated with an F, her mother Emma was designated with an F, and her daughter, Vivienne, was designated with an F. There you have three generations of imbeciles. Enough.

Haughlin, impressed that Nazi Germany adopted his ideas, had this to say:

The fact that a great state like the German Republic, which for many centuries has helped furnish the best that science has bred, has in its wisdom seen fit to enact a national eugenic legislative act providing for the sterilization of hereditarily defective persons seems to point the way for an eventual worldwide adoption of this idea.

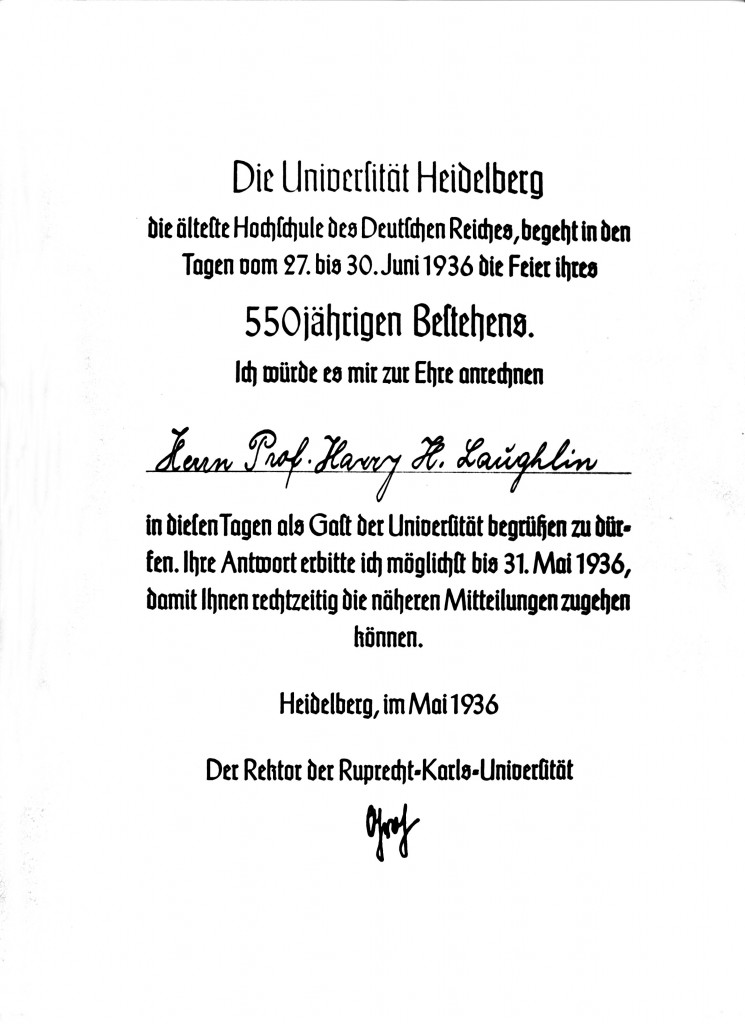

In 1936, Laughlin was invited by the Nazis to receive an honorary degree of Doctor of Medicine at the University of Heidelberg for his work in the “science of racial cleansing.”

Here is Carrie Buck shortly before she died.

Here is Carrie Buck shortly before she died.

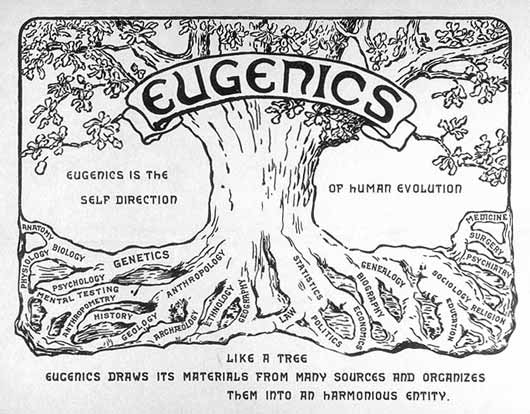

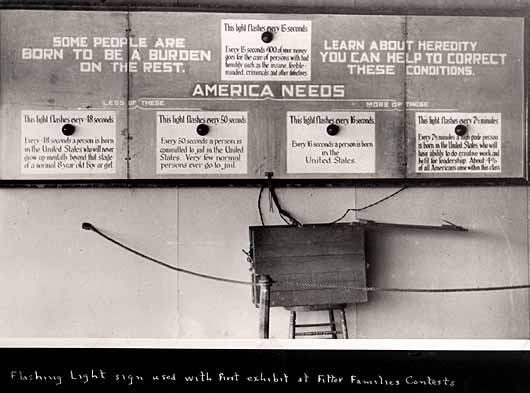

Here are several pieces of American propaganda about Eugenics.

This one says, “Some people are born to be a burden on the rest. Learn about heredity. You can help to correct these conditions.”

This piece of propaganda says “Eugenics is the self direction of human evolution.”

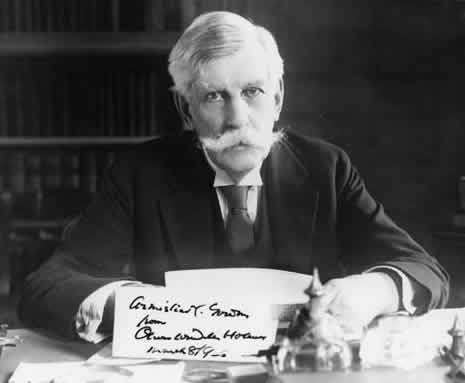

Speaking of social darwinism, and surivival of the fittest, here is Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., who firmly believed that “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

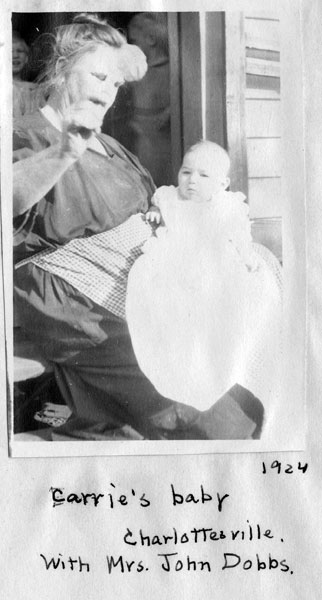

Buck’s daughter, Vivian, was raised by foster parents, This is Vivian at 6 months old. She flunked her IQ test. So she was also deemed an imbecile:

It was Estabrook’s habit to photograph the subjects of his eugenical family studies, and one surviving photo shows Alice Dobbs holding Carrie’s baby. It appears that Mrs. Dobbs is holding a coin in front of Vivian’s face in an attempt to catch her attention. The baby looks past her, staring into the distance, apparently failing the test. Estabrook described that moment during his testimony at trial a few days later: “I gave the child the regular mental test for a child of the age of six months, and judging from her reaction to the tests I gave her, I decided she was below the average.”

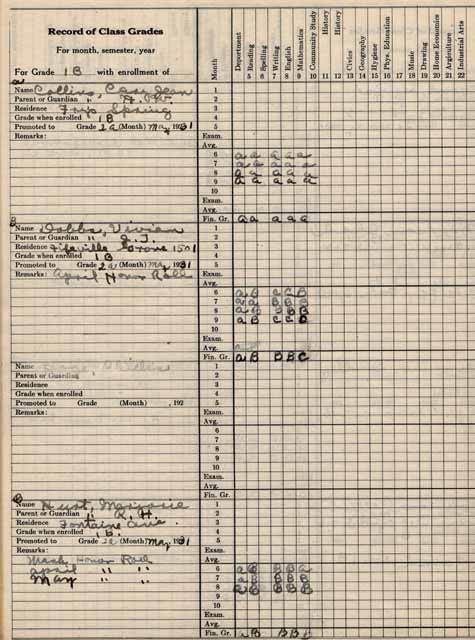

In case you were wondering, the child was not an imbecile. Here is her report card from first grade. She was a solid B student, with an A in deportment, and on the honor roll.

Vivian died at the age of 8 due to intestinal diseases.

Despite her sterilizations, Buck would go on to be married, twice. First to William Eagle.

25 year after William’s death, Buck married Charlie Deatmore.

Here is Carrie Buck shortly before she died.

Here is a sign in Virginia to commemorate Buck v. Bell.

Griswold v. Connecticut

Here is Estelle Griswold, the lead plaintiff at the Planned Parenthood Center of New Haven, Connecticut.

Here is a photograph of Dr. C. Lee Buxton and Estelle Griswold after their arrest.

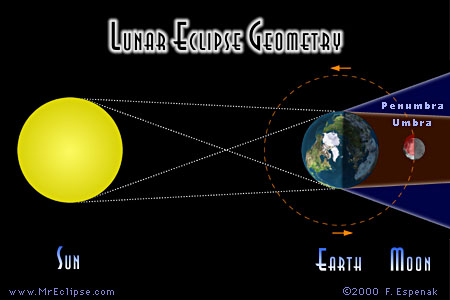

A penumbra is a partial shadow outside the complete shadow of an opaque body.