Bailey v. United States considers when the detention of a person outside the vicinity of the premises to be searched violates the Fourth Amendment. Justice Kennedy’s majority opinion for the court is grounded in a balancing test (shocker!). The balance considers the “limited intrusion on personal liberty” and the “special law enforcement interests at stake.“

Detentions incident to the execution of a search warrant are reasonable under the Fourth Amendment because the limited intrusion on personal liberty is outweighed by the special law enforcement interests at stake.

Justice Scalia, joined by Justices Ginsburgsand Kagan (a trio that I much adore) wrote “separately to emphasize why the Court of Appeals’ interest-balancing approach to this case—endorsed by the dissent—is incompatible with the categorical rule set forth in Michigan v. Summers,”

The existence and scope of the Summers exception were predicated on that balancing of the interests and burdens. But—crucially—whether Summers authorizes a seizure in an individual case does not depend on any balancing, because the Summers exception, within its scope, is “categorical.” Muehler v. Mena, 544 U. S. 93, 98 (2005). That Summers establishes a categorical, bright-line rule is simply not open to debate—Summers itself insisted on it.

Scalia also takes issue with Justice Breyer’s balancing-test-dissent:

The Court of Appeals’ mistake, echoed by the dissent, was to replace that straightforward, binary inquiry with open-ended balancing. Weighing the equities—Bailey “posed a risk of harm to the officers,” his detention “was not unreasonably prolonged,” and so forth—the Court of Appeals proclaimed the officers’ conduct, “in the circumstances presented, reasonable and prudent.” 652 F. 3d 197, 206 (CA2 2011) (internal quotation marks and brackets omitted); see also post, at 3–4 (opinion of BREYER, J.). That may be so, but it is irrelevant to whether Summers authorized the officers to seize Bailey without probable cause. To resolve that issue, a court need ask only one question: Was the person seized within “the immediate vicinity of the premises to be searched”? Ante, at 11.

Scalia also offers an interesting discussion about categoricalism in the context of the Fourth Amendment:

Summers embodies a categorical judgment that in one narrow circumstance—the presence of occupants during the execution of a search warrant—seizures are reasonable despite the absence of probable cause. Summers itself foresaw that without clear limits its excep- tion could swallow the general rule: If a “multifactor balancing test of ‘reasonable police conduct under the circumstances’” were extended “to cover all seizures that do not amount to technical arrests,” it recognized, the “‘protections intended by the Framers could all too easily disappear in the consideration and balancing of the multifarious circumstances presented by different cases.’” 452 U. S., at 705, n. 19 (quoting Dunaway, supra, at 213 (some internal quotation marks omitted)). The dissent would harvest from Summers what it likes (permission to seize without probable cause) and leave behind what it finds uncongenial (limitation of that permission to a narrow, categorical exception, not an open-ended “reasonableness” inquiry).

The dissent purports to agree “that the question involves drawing a line of demarcation granting a categorical form of detention authority.” Post, at 3. What the dissent misses is that a “categorical” exception must be defined by categorical limits. Summers’ authorization to detain applies only to “occupants”—a bright-line limitation that the dissent’s “reasonably practicable” test discards altogether.

Scalia closes by faulting the difficulty of applying balancing tests.

Summers’ clear rule simplifies the task of officers who encounter occupants during a search. “[I]f police are to have workable rules, the balancing of the competing interests . . . ‘must in large part be done on a categorical basis—not in an ad hoc, case-by-case fashion by individual police officers.’” Id., at 705, n. 19 (quoting Dunaway, supra, at 219–220 (White, J., concurring)); see also Arizona v. Gant, 556 U. S. 332, 352–353 (2009) (SCALIA, J., concurring). But having received the advantage of Sum-mers’ categorical authorization to detain occupants incident to a search, the Government must take the bitter with the sweet: Beyond Summers’ spatial bounds, seizures must comport with ordinary Fourth Amendment principles.

This phrase,”spatial bounds,” has been used in exactly one Supreme Court opinion before today. Justice Kennedy’s opinion in Lawrence v. Texas.

Liberty protects the person from unwarranted government intrusions into a dwelling or other private places. In our tradition the State is not omnipresent in the home. And there are other spheres of our lives and existence, outside the home, where the State should not be a dominant presence. Freedom extends beyond spatial bounds. Liberty presumes an autonomy of self that includes freedom of thought, belief, expression, and certain intimate conduct. The instant case involves liberty of the person both in its spatial and more transcendent dimensions.

How did neither RBG nor Kagan pick that up?! I saw it, and thought, no way Scalia would go there. He did.

I wonder if Nino was sending a signal to AMK about SSM?

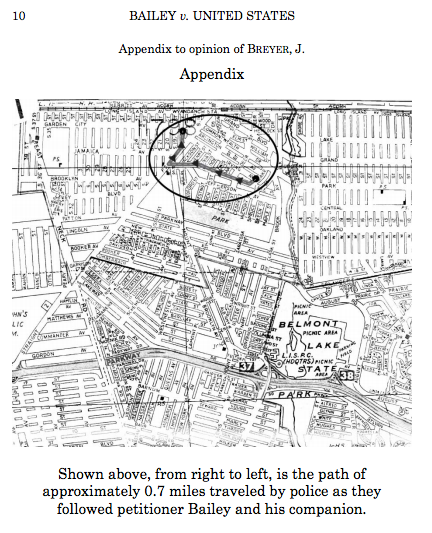

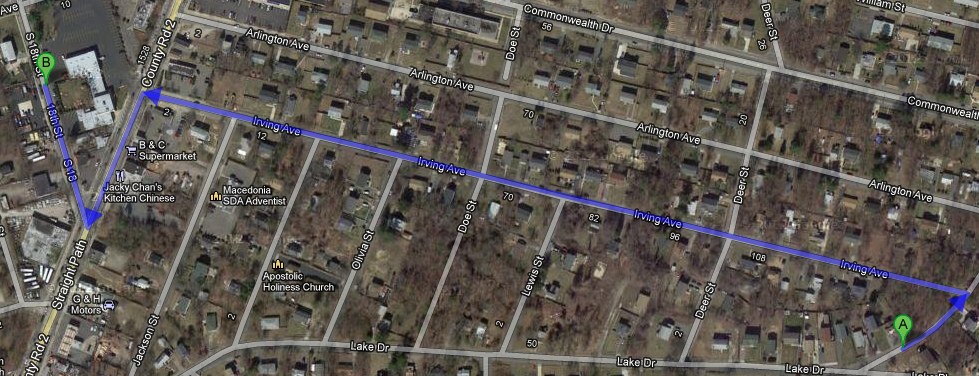

The dissent, from Justice Breyer, joined by Thomas and Alito, focuses on balancing tests. “Considerations of this kind reveal the dangers inherent in the majority’s effort to draw a semi-bright line.”

In sum, I believe that the majority has substituted a line based on indeterminate geography for a line based on realistic considerations related to basic Fourth Amendment concerns such as privacy, safety, evidence destruction, and flight. In my view, these latter considerations should govern the Fourth Amendment determination at issue here. I consequently dissent.