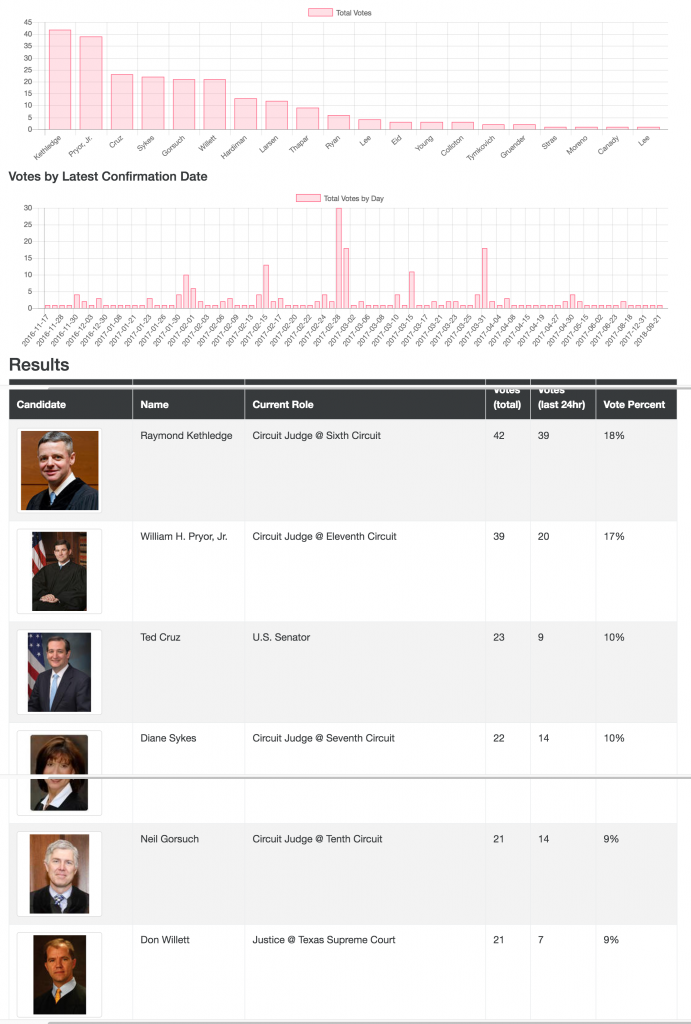

Using LexPredict’s FantasySCOTUS, a Supreme Court prediction market I created in 2009, I surveyed more than a hundred Federalist Society lawyers about who they think President Trump will nominate. (USA Today has already featured our odds). As they swiped their favorite candidate on my iPad, each attorney explained the pros and cons of the short list. The results, which fall into three categories—the front runners, the Kennedy clerks, and the dark horses—provide insights into a process shrouded in secrecy.

I discuss these results in my new essay in The Weekly Standard.

First, the Front Runners:

On February 13, 2016—four hours after Justice Scalia had passed away—CBS News hosted a debate for the GOP presidential candidates. The first question went to Trump. “You’ve said that the president shouldn’t nominate anyone in the rest of his term to replace Justice Scalia,” moderator John Dickerson said. “If you were president, and had a chance with 11 months left to go in your term, wouldn’t it be an abdication to conservatives in particular, not to name a conservative justice with the rest of your term?” Without hesitation, Trump answered, if he was elected, “we could have a Diane Sykes, or you could have a Bill Pryor, we have some fantastic people.” Ten months later, these two distinguished jurists are still the frontrunners.

After the announcement that Jeff Sessions would be nominated as Attorney General, the tide at the Mayflower rolled to Alabama’s native son, Judge William H. Pryor, Jr. A member of the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals, with chambers in Birmingham, Pryor was the preferred pick of the majority of attorneys I spoke with. The shared sentiment was that Sessions would most likely push for Pryor. (Although, a dissenting view was that Trump would be leery of selecting too many white guys from Alabama.) Consistently, the Federalists viewed him as a committed originalist, who was a worthy replacement for Justice Scalia. Even Pryor’s defenders, however, acknowledged his liabilities. Pryor stated that Roe v. Wade was the “worst abomination of constitutional law in our history.” During his 2003 confirmation hearing, he stood by that comment, and reiterated his “personal belief” that “the case [was] unsupported by the text and structure of the Constitution.”

Yet, Pryor’s fortitude during his hearing was seen as a virtue. Supporters viewed him as a rock-ribbed conservative who would not drift to the left—unlike past disappointing picks from Republican presidents. Fittingly, before the 2000 election, Pryor offered this supreme supplication at a Federalist Society meeting: “Please, God, no more Souters.” Pryor was universally praised as the antithesis of President George H.W. Bush’s first nomination, moderate-turned-liberal David H. Souter. The only lingering question was whether Trump should make the tougher selection for his first pick, or hold off on Pryor till later. One lawyer noted that if President Reagan had nominated Robert Bork beforeAntonin Scalia, we may have never known of a Justice Anthony Kennedy.

After Judge Pryor, most Federalist Society members favored Judge Diane S. Sykes of the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals. In 2004, President Bush plucked Sykes from the Wisconsin Supreme Court, where she was elected five years earlier. Over the past decade, Sykes has distinguished herself as a principled jurist, with important decisions securing Second Amendment rights and protecting religious liberty. Having successfully run for elected office—something federal judges never have to do—Sykes has an endearing personality with a firm handshake. Further, at least in confidence, Federalists acknowledged the symbolism of a Trump administration nominating a female jurist. Though, some hoped to keep her on the farm team even longer to fill Justice Ginsburg’s seat.

Sykes’s biggest liability is one she cannot control: She turns 59 in December. Consistently, lawyer after lawyer at the convention told me how much they liked Sykes, but favored Pryor, who was five years younger. For a lifetime appointment, age is more than just a number. By contrast, Chief Justice Roberts, and Justices Scalia and Kagan, were all 50 when nominated. Justice Thomas was only 43. But the nomination would not be unprecedented. Justices Alito and Breyer were both 56. Justice Ginsburg was appointed at the age of 60. For whatever it’s worth, women live on average five years longer than men, 81.2 years to 76.4 years, which would cancel out Judge Pryor’s age-advantage.

Second, the Kennedy Clerks:

At the Mayflower, there was also a burgeoning support for two former law clerks of Justice Kennedy. First, Judge Raymond Kethledge was appointed by President Bush to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals when he was only 42. He was easily confirmed, as part of a compromise with Senate Democrats to break a judicial filibuster. Eight years later, though he has not authored many decisions on hot-button issues—he did rule against the IRS in a suit brought by the Tea Party Patriots—Kethledge’s opinions have been recognized as an “exemplar of good legal writing.”

Second, Judge Neil Gorsuch was confirmed to the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals at the young age of 39. After a decade on the Denver-based court, Gorsuch has built his reputation as a committed originalist, who has questioned judicial deference to the administrative state. While there was not as much excitement to elevate Kethledge and Gorsuch now, the attorneys I spoke with preferred they remain available for a future nomination.

There was a sense of apprehension that Justice Kennedy, the Court’s perennial swing vote, may be averse to letting Donald Trump appoint his replacement. One way to mollify that concern, several lawyers told me, is by choosing one of Justice Kennedy’s former law clerks. Gorsuch and Kethledge would fill that role well. Brett Kavanaugh of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, who also clerked for Justice Kennedy, was also seen as a possible future nominee, even though he was omitted from Trump’s list.

Finally, the Dark Horses:

While most Federalist Society lawyers supported the conventional wisdom, and others favored the Kennedy clerks, several boldly predicted that President Trump may surprise everyone with a dark horse nomination. Leading the pack was Justice Joan Larsen of the Michigan Supreme Court. At only 47 years, Justice Larsen was consistently identified as a possible “sleeper candidate” for the High Court. She clerked for Justice Scalia in 1994, and was appointed to Michigan’s High Court in 2015. Her largest perceived liability, I learned, was a strikingly short-tenure on the bench. A number of Federalists told me she should be kept on the short-list to watch her jurisprudence develop. She may be a possible replacement pick for Justice Ginsburg in the future, to the extent that President Trump wants to select a female for that seat. Though, the lawyers insisted that the White House should not bother putting her on the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals. There is no need to risk a confrontational confirmation hearing that could be blocked by blue slips from Michigan’s two Democratic senators.

Another unlikely candidate—particularly popular among the Lone Star State’s Federalist delegation—was Justice Don Willett of the Texas Supreme Court. During the Republican primary, Willett mocked Trump on Twitter, with a now-legendary haiku: “Who would the Donald / Name to #SCOTUS? The mind reels. / Weeps – can’t finish tweet.” Fortunately, his twitter finger is second only to his judicial pen. Willett is universally praised by the libertarian wing of the Federalist Society, for his vigorous protection of economic liberty and property rights. Willett’s charming witticism, some said, was also viewed as a positive for an eventual confirmation hearing.

The final dark horse is perhaps the darkest of all: Senator Ted Cruz. Though not on the list, the former Supreme Court clerk and litigator was seen as a possible unifying pick. Cruz delivered a rousing keynote address to the Federalist Society convention, and brought the house down. The conservative and libertarian lawyers in the room—many of whom supported Cruz in the primary (myself included)—would be thrilled to see him on the Court. He is a resolute and committed originalist who, as his brief stint in the Senate shows, does not bend his principles. In many respects, that philosophy is more suited for the nine-member Court than the hundred-member Senate. As well, some of his Democratic and Republican colleagues would be all too happy to confirm him in order to get him out of the Senate! The Texan, who is only forty-five, can likely be re-elected for the next half-century. President Trump may also not want the limited-government Cruz as a thorn in his side. Lawyer after lawyer told me how much they would love Cruz on the Court—an ideal replacement for Justice Scalia—if only he would want the job. Most of the Court’s docket concerns boring matters, like tax or bankruptcy—the sexy constitutional cases are quite rare.

In conclusion, I note that ultimately, the decision will be made by a President whose formative experience was firing and hiring reality-show candidates on national television.

Ultimately, of course, the decision will be made by a single person: President Donald J. Trump. No doubt, advisers on the Justice Department Transition Team and the Federalist Society will provide the President with extensive briefings on each candidate, but as with all nominations, the decision will ultimately be personal. A brief interview in the White House—maybe 15 or 20 minutes—will decide who the next Justice is. With our reality-show president, a judge’s sweaty palms, shiny brow, or sore throat, can frustrate a lifetime’s aspiration in an instant. You’re fired! With the right chemistry, that jurist will fill Justice Scalia’s seat for the next generation. You’re hired!