The current debate about so-called “sanctuary cities” (a term without any consistent meaning) centers around 8 U.S.C. s. 1373, which provides that a state “may not prohibit, or in any way restrict, any government entity or official from sending to, or receiving from, the Immigration and Naturalization Service information regarding the citizenship or immigration status, lawful or unlawful, of any individual.” The constitutionality of this provision implicates two doctrines: the spending clause and the commandeering principle.

With respect to the former issue, I’ve reserved judgment because there is a widespread uncertainty about how much funds would actually be withheld; what categories of funds would be withheld; and whether those funds are tied to purely discretionary grants, for which the clear statement rule has less bite. In January, I noted that New York City may be at risk of losing only $9 million in grants–a tiny fraction of the city’s $90 billion annual budget. More recently, in San Francisco v. Trump, the Justice Department explained that the federal government is still “in the process of identifying, in its discretion, what actions, if any, can lawfully be taken in order to encourage state and local jurisdictions to comply with federal law.” I suspect at some point, a notice will be placed in the federal register, stating the terms on which funding will be provided next year. This should address notice issues. No action has been taken to remove any sources of funding. The question in the abstract is still premature, though the district court in the San Francisco case seemed ready to heap another nationwide injunction on the pile. Viva la resistance!

The second issue, concerning commandeering, however, is ripe for review: Can Congress, through section 1373, preempt a state law that prohibits local municipalities from voluntarily sharing information about immigrants with the federal government. The answer to this question is fairly involved, does not flow from a straightforward application of New York, Printz, or Reno v. Condon, and involves (of all things) a statute requiring states to report missing children.

Our inquiry begins with Printz. In Solicitor General Waxman’s brief, the government explained that if the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act was invalidated, other laws would be in jeopardy: “Today, as well, several federal statutes require participation by state and local officials in implementing federal regulatory schemes.” Of the seven statutes he list, six are run-of-the-mill conditional spending measures, involving educational or environmental grants. States were “required” to do something, but if they didn’t, the executive branch would hold back some money. Justice Scalia’s majority opinion in Printz dismissed the relevance of these six regimes, writing, “Some of these are connected to federal funding measures, and can perhaps be more accurately described as conditions upon the grant of federal funding than as mandates to the States.” But the first statute listed, 42 U.S.C. s. 5779(a), imposed a requirement on states to report missing children. It was not tied to the withholding of funds.

Before we get to section 5779, I’ll take a brief detour to 42 U.S.C. s. 5780. Though not cited in Printz, it is almost a mirror image of Section 1373. It provides (in part):

Each State reporting under the provisions of this section and section 5779 of this title shall—

(1) ensure that no law enforcement agency within the State establishes or maintains any policy that requires the observance of any waiting period before accepting a missing child or unidentified person report;

(2) ensure that no law enforcement agency within the State establishes or maintains any policy that requires the removal of a missing person entry from its State law enforcement system or the National Crime Information Center computer database based solely on the age of the person;

(3) provide that each such report and all necessary and available information, which, with respect to each missing child report, shall include…

Subparagraphs (1) and (2) prohibits states from enacting laws that would prevent the sharing of information in a timely fashion. This is on all fours with Section 1373. Subparagraph (3) provides that very specific pieces of information that must be shared. Whatever burden exists, this is not a minimal, ministerial one. If Section 1373 is unconstitutional, there is a strong argument that Section 5789 is unconstitutional.

In any event, in Printz, the government focused on 42 U.S.C. s. 5779(a), which provides:

Each Federal, State, and local law enforcement agency shall report each case of a missing child under the age of 21 reported to such agency to the National Crime Information Center of the Department of Justice.

This is not a conditional spending program. 42 U.S.C. s 4775, enacted in the same statute, allows the executive branch to give grants to “public agencies or nonprofit private organizations,” but there is not even the faintest hint in s 4776, let alone a clear statement, that state and local law enforcement agencies that fail to comply are at risk of losing funding. In his reply brief for petitioner in Printz, Steven Halbrook wrote that “Current federal laws provide that States shall report missing children . . . in exchange for use of the National Crime Information Center.”

That explanation did not fly at oral arguments, when Justice Breyer pinned Halbrook about the constitutionality of this provision.

Stephen G. Breyer: That’s just the question that I have, actually. I mean, if you track this through, I take it there’s a statute, for example, which says that States have to report missing children, right?

Stephen P. Halbrook: –A statute that’s based on highway funding, yes.

Stephen G. Breyer: It’s not… I just see they’re setting up a task force, and they say in the task force… what it says here is every Federal, State, and local law enforcement shall report each case of a missing child under age 18.

Stephen P. Halbrook: To the NCIC.

Stephen G. Breyer Yes, right. Period.

Stephen P. Halbrook: Yes, right.

Stephen G. Breyer: Not whether you take money, you don’t take money, so I take it you’re saying that’s unconstitutional, too.

Stephen P. Halbrook: Well, I interpret that as being based on NCIC.

Stephen G. Breyer: I don’t see anything here that says you have to do it only if you take money.

Stephen P. Halbrook: Your Honor, when you look at the other provisions establishing the NCIC–

Stephen G. Breyer: Then if it says you only have to do it if you take money, then I’m not right. It’s not a good example. There must be an example, maybe it’s this case, where Congress has the power under the Commerce Clause to say, report some things, right? But the issue is whether it’s necessary and proper.

Breyer was right–the statute had nothing to do with highway funds. Assuming he sticks with his Printz dissent–is it perpetual?–the federal government could compel states to disclose information. Though, as we shall see, that is not what Section 1373 does not require the state to share any information.

Justice O’Connor also asked about the Missing Child program in Printz. Halbrook again tried to characterize the program as “voluntary.”

Sandra Day O’Connor: Is that… excuse me. Now, the Government has… the SG has filed a brief citing any number of cases, instances through the years where Congress has required States or local officials to perform some duties, and you assert that in every case it was linked somehow to funding?

Stephen P. Halbrook: As far as we could determine, the statutes we looked at that were prominently cited by the Government… the one that you mentioned, the fatalities reporting, and then the reporting the missing children relates to the National Crime Information Center, which is a voluntary system of record reporting between the Federal Government and the States… and we haven’t found an instance where there was not some nexus with receipt of a grant or some other–

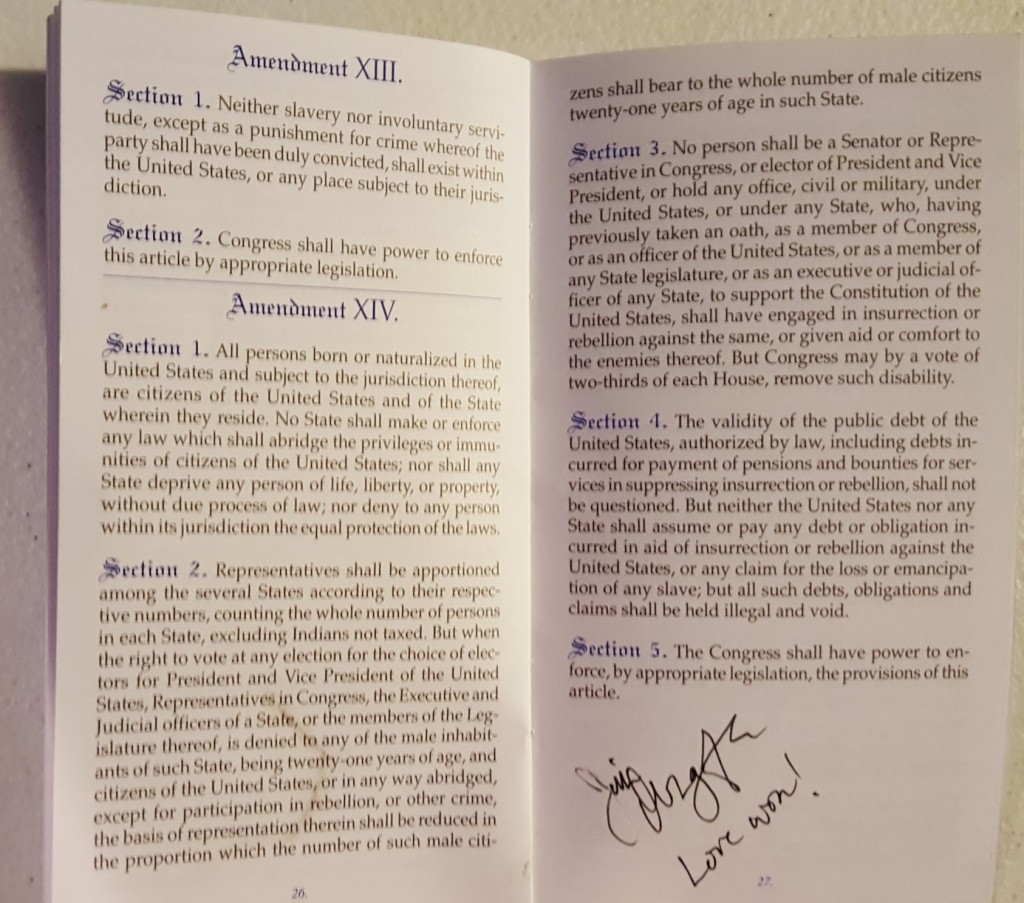

O’Connor didn’t push further during arguments–the Chief interjected after Halbrooks’s response–but she did dedicate half of her two-paragraph concurring opinion to this precise issue, noting that such a statute differs from the Brady Act. She wrote:

In addition, the Court appropriately refrains from deciding whether other purely ministerial reporting requirements imposed by Congress on state and local authorities pursuant to its Commerce Clause powers are similarly invalid. See, e.g., 42 U.S.C. § 5779(a) (requiring state and local law enforcement agencies to report cases of missing children to the Department of Justice). The provisions invalidated here, however, which directly compel state officials to administer a federal regulatory program, utterly fail to adhere to the design and structure of our constitutional scheme

To this regime, Scalia’s majority opinion punted, partially:

[O]ther [statutes], which require only the provision of information to the Federal Government, do not involve the precise issue before us here, which is the forced participation of the States’ executive in the actual administration of a federal program. We of course do not address these or other currently operative enactments that are not before us; it will be time enough to do so if and when their validity is challenged in a proper case. For deciding the issue before us here, they are of little relevance. Even assuming they represent assertion of the very same congressional power challenged here, they are of such recent vintage that they are no more probative than the statute before us of a constitutional tradition that lends meaning to the text. Their persuasive force is far outweighed by almost two centuries of apparent congressional avoidance of the practice.

The Missing Child law was enacted in 1990. Due to its “recent vintage,” such a practice would not be dispositive of the constitutionality of a federal law that mandates the sharing of information.

Printz was argued on 12/3/96, and decided on 6/27/97. Section 1373–the provision at issue in the sanctuary cases–was signed into law on August 22, 1996. Query if anyone was aware of what Printz would hold a year later when the immigration law was enacted.

In any event, eleven days after Section 1373 was signed into law, New York City sought to enjoin it. (Irony of ironies, Rudy Giulliani of all people was the Mayor at the time–how things change!). Less than a month after Printz was decided, on July 18, 1997, Judge Koeltl (SDNY) ruled against the City. His opinion recognized that the majority opinion in Printz, as well as Justice O’Connor’s concurring opinion, flagged the possible commandeering issues attending the missing-child statute. However, the court distinguished Section 1373 from the missing-child statute:

In this case, Section [1373 is] even less intrusive on state sovereignty than those mandatory reporting statutes whose validity the Supreme Court explicitly refrained from deciding. Sections 434 and 642 do not require any reporting by any state and local officials. They merely prevent state and local authorities from interfering with the voluntary provision of information. They do not contravene the teaching of Printz that Congress cannot conscript state officers to carry out a federal regulatory program.

Critically, nothing in Section 1373 actually requires that the states provide information to the federal government. Rather, it merely prevents the state from prohibiting officials from providing information to immigration officials.

New York had another argument that was raised more forcefully on appeal: the law intruded on their sovereignty by controlling how they manage their employees. The Second Circuit characterized the city’s claim this way:

With regard to its argument concerning its power to direct its workforce, the City argues that inherent in our dual-sovereignty system is the power of state and local governments to determine the duties and responsibilities of their employees.

Judge Winter, writing for Judges Walker and Jacobs, acknowledged that New Yorks’s “concerns are not insubstantial.”

The obtaining of pertinent information, which is essential to the performance of a wide variety of state and local governmental functions, may in some cases be difficult or impossible if some expectation of confidentiality is not preserved. Preserving confidentiality may in turn require that state and local governments regulate the use of such information by their employees. Finally, it is undeniable that Sections 434 and 642 do interfere with the City’s control over confidential information obtained in the course of municipal business and over its employees’ use of such information.

The court punted, somewhat, based on the fact that New York brought a challenge premised on the sanctuary city executive order. The order, in short, only prevents disclosure of confidential information to federal officials, but to no one else. It’s purpose, the court finds, is not really to protect confidentiality, but to frustrate a federal policy.

The Executive Order is not a general policy that limits the disclosure of confidential information to only specific persons or agencies or prohibits such dissemination generally. Rather, it applies only to information about immigration status and bars City employees from voluntarily providing such information only to federal immigration officials. On its face, it singles out a particular federal policy for non-cooperation while allowing City employees to share freely the information in question with the rest of the world. It imposes a policy of no-voluntary-cooperation that does not protect confidential information generally but does operate to reduce the effectiveness of a federal policy. For example, the City argues that the Executive Order is essential to the provision of municipal services and to the reporting of crimes because these governmental functions often require the obtaining of information from aliens who will be reluctant to give it absent assurances of confidentiality. But again, the Executive Order does not on its face prevent the sharing of information with anyone outside the INS. . . .

This reasoning has a circularity to it. A state policy that frustrates a federal law is preempted (such as parts of SB 1070 in Arizona v. United States). But if the federal law is unconstitutional, because it intrudes on state sovereignty, it cannot preempt the state law. The 2nd Circuit dances around this issue.

Ultimately, the court upholds the law based on the challenge brought, leaving open the question of whether a more narrowly tailored executive order would survive scrutiny:

Given the circumscribed nature of our inquiry, we uphold Sections 434 and 642. Essentially, the foregoing discussion relating to the power of states to command passive resistance to federal programs governs the analysis here. The effect of those Sections here is to nullify an Order that singles out and forbids voluntary cooperation with federal immigration officials. Whether these Sections would survive a constitutional challenge in the context of generalized confidentiality policies that are necessary to the performance of legitimate municipal functions and that include federal immigration status is not before us and we offer no opinion on that question.

In an earlier part of the opinion, the court noted that New York’s efforts were not truly designed to protect confidentiality, as officials could share information with non-federal officials. Rather, it was designed to frustrate federal programs. Indeed, Judge Winter compares New York’s obstruction to the massive resistance following Brown v. Board of Education. (This analogy is imprecise for reasons I am developing in my work on Cooper v. Aaron, but it will suffice here).

The City’s sovereignty argument asks us to turn the Tenth Amendment’s shield against the federal government’s using state and local governments to enact and administer federal programs into a sword allowing states and localities to engage in passive resistance that frustrates federal programs. If Congress may not forbid states from outlawing even voluntary cooperation with federal programs by state and local officials, states will at times have the power to frustrate effectuation of some programs. Absent any cooperation at all from local officials, some federal programs may fail or fall short of their goals unless federal officials resort to legal processes in every routine or trivial matter, often a practical impossibility. For example, resistance to Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 74 S.Ct. 686, 98 L.Ed. 873 (1954), was often in the nature of a refusal by local government to cooperate until under a court order to do so.

By the time New York City filed its petition for certiorari, the Court had already granted review in what was then Condon v. Reno from the 4th Circuit. New York claimed that the 2nd Circuit’s decision conflicted with the 4th Circuit’s decision, which invalidated the federal Driver’s Privacy Protection Act. SG Waxman filed a short BIO, noting that there was no conflict with Condon, and–echoing SDNY–wrote that “The provisions challenged here, which impose no reporting requirements on the States, are ‘even less intrusive on state sovereignty than those mandatory reporting statutes whose validity the Supreme Court explicitly refrained from deciding’ in Printz.” The Court denied review in New York City’s case, without any noted dissent.

That brings us to Reno v. Condon, which is relevant, but not dispositive. The Driver’s Privacy Protection Act of 1994 (again, before Printz) “regulates the disclosure and resale of personal information contained in the records of state DMVs.” South Carolina challenged the federal ban on disclosing personal information, arguing that it imposed burdens on the state:

South Carolina contends that the DPPA violates the Tenth Amendment because it “thrusts upon the States all of the day-to-day responsibility for administering its complex provisions,” Brief for Respondents 10, and thereby makes “state officials the unwilling implementors of federal policy,” id., at 11.3 South Carolina emphasizes that the DPPA requires the State’s employees to learn and apply the Act’s substantive restrictions, which are summarized above, and notes that these activities will consume the employees’ time and thus the State’s resources

Writing for a unanimous Court, Chief Justice Rehnquist rejected the challenge:

We agree with South Carolina’s assertion that the DPPA’s provisions will require time and effort on the part of state employees, but reject the State’s argument that the DPPA violates the principles laid down in either New York or Printz. We think, instead, that this case is governed by our decision in South Carolina v. Baker, 485 U.S. 505, 108 S.Ct. 1355, 99 L.Ed.2d 592 (1988). . . . .

Like the statute at issue in Baker, the DPPA does not require the States in their sovereign capacity to regulate their own citizens. The DPPA regulates the States as the owners of data bases. It does not require the South Carolina Legislature to enact any laws or regulations, and it does not require state officials to assist in the enforcement of federal statutes regulating private individuals. We accordingly conclude that the DPPA is consistent with the constitutional principles enunciated in New York and Printz.

This case does not resolve the sanctuary city debate, but it does come much closer than Printz does. Specifically, Condon discusses how Congress can regulate the terms on which states can disclose information already in their possession, but it does not discuss what happens if a state refuses to comply with the federal program.

Yet, there is a passage in Condon that I had forgotten about:

The DPPA’s prohibition of nonconsensual disclosures is also subject to a number of statutory exceptions. For example, the DPPA requires disclosure of personal information . . .

Requires?! Like the missing-child law?

18 U.S.C. 2721(b), which was not cited by SG Waxman in Printz, provides:

Personal information referred to in subsection (a) shall be disclosed for use in connection with matters of motor vehicle or driver safety and theft, motor vehicle emissions, motor vehicle product alterations, recalls, or advisories, performance monitoring of motor vehicles and dealers by motor vehicle manufacturers, and removal of non-owner records from the original owner records of motor vehicle manufacturers to carry out the purposes of titles I and IV of the Anti Car Theft Act of 1992, the Automobile Information Disclosure Act (15 U.S.C. 1231 et seq.), the Clean Air Act (42 U.S.C. 7401 et seq.), and chapters 301, 305, and 321–331 of title 49, and, subject to subsection (a)(2), may be disclosed as follows:

(1) For use by any government agency, including any court or law enforcement agency, in carrying out its functions, or any private person or entity acting on behalf of a Federal, State, or local agency in carrying out its functions.

…

(4) For use in connection with any civil, criminal, administrative, or arbitral proceeding in any Federal, State, or local court or agency or before any self-regulatory body, including the service of process, investigation in anticipation of litigation, and the execution or enforcement of judgments and orders, or pursuant to an order of a Federal, State, or local court.

The DPPA is not (as far as I can tell) a spending-clause law, and was upheld against a commandeering challenge. Inadvertently, perhaps, the Court passed on the constitutionality of a statute requiring the provision of information from DMVs. I don’t think the issue was raised anywhere in the papers, so it was not presented to the Court.

There is, of course, another case that is on point, which I mentioned earlier: Arizona v. United States. To date, jurisdictions such as San Francisco and Santa Clara, brought proactive suits against the federal government. AG Sessions could take a page out of AG Holder’s playbook: turn the sword into a shield, and sue to enjoin those state laws as preempted. As I wrote on National Review the day before the inauguration,

Arizona’s S.B. 1070, commonly referred to as the “show your papers” law, gave local law enforcement the power to arrest aliens who were in violation of federal immigration law. The Supreme Court invalidated this provision of S.B. 1070, finding that it “stands as an obstacle to the accomplishment and execution of the full purposes and objectives of Congress.” Federal control over immigration, the Court held, is “so pervasive . . . that Congress left no room for the States to supplement it.” In other words, state immigration policies that interfere with the comprehensive federal immigration scheme are preempted. If Arizona is not allowed to adopt a policy that arguably helps federal law enforcement (by arresting those subject to removal), then California certainly cannot adopt a policy that explicitly impedes federal law enforcement. This precedent does not help sanctuary cities.

There is a tension, however, between these two cases. Under Printz, local officials cannot be conscripted to enforce federal law-enforcement duties. At the same time, a state law or policy that serves as an “obstacle” to Congress’s federal immigration scheme violates the holding of Arizona. Conservative attorneys general should cheerfully point out this tension to the courts. For California to prevail, the Supreme Court will have to shake things up. Printz’s commandeering doctrine will be expanded, thus reigning in the power of the central government; Arizona’s preemption analysis will be curtailed, which expands a state’s internal police powers.

Where does this leave us? This constitutionality of Section 1373 is not foreclosed by precedent one way or the other. There is a tension.

Critics contend that Printz’s commandeering principle lacks any textual grounding in the Constitution. This isn’t quite right. Justice Scalia’s opinion explains that Brady Act failed not because of the 10th Amendment, standing by itself, but because it was not a “proper” exercise of federal power. The notion of separating “necessary” and “proper” into different elements was employed in NFIB v. Sebelius, but this doctrine was previously alluded to in New York, and employed in Printz. Scalia’s opinion explains:

What destroys the dissent’s Necessary and Proper Clause argument, however, is not the Tenth Amendment but the Necessary and Proper Clause itself.13 When a “La [w] … for carrying into Execution” *924 the Commerce Clause violates the principle of state sovereignty reflected in the various constitutional provisions we mentioned earlier, supra, at 2376-2377, it is not a “La[w] … proper for carrying into Execution the Commerce Clause,” and is thus, in the words of The Federalist, “merely [an] ac[t] of usurpation” which “deserve[s] to be treated as such.” The Federalist No. 33, at 204 (A. Hamilton). … We in fact answered the dissent’s Necessary and Proper Clause argument in New York: “[E]ven where Congress has the authority under the Constitution to pass laws requiring or prohibiting certain acts, it lacks the power directly to compel the States to require or prohibit those acts…. [T]he Commerce Clause, for example, authorizes Congress to regulate interstate commerce directly; it does not authorize Congress to regulate state governments’ regulation of interstate commerce.”

It may be necessary to require local law enforcement officials to perform background checks while the instant background check system is developed, but it was not proper because of the intrusion onto state sovereignty. It may be necessary to impose an individual mandate to ensure a functional health care market with both guaranteed issue and community rating, but it was not proper to intrude on the sovereignty of the individual. The question concerning Section 1373 this: is it proper for Congress to prevent states from preventing their local official from voluntarily providing immigration information to federal officials?

To strike down Section 1373, the Court will need to find it is not proper, by building on New York, Printz, and NFIB. It is not enough to cite Printz and go home. (This is what fair-weather federalists will hope for!). The Court will have to expand doctrine. As I wrote in NRO, “[t]his rejiggering of precedent would be a boon to federalism,” especially if there is “buy-in from the liberal justices.”