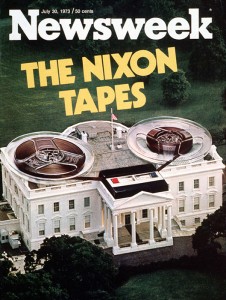

In many of the canonical separation of powers cases, the Court seems to recognize that there is a non-delegation doctrine problem lurking in the background, but then goes on to resolve it on different grounds.

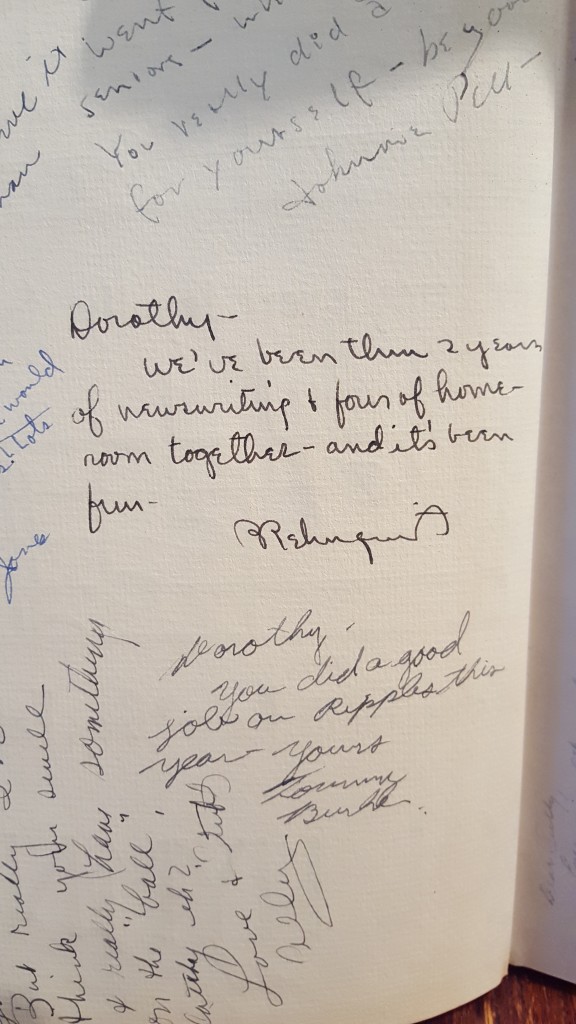

First, consider Humphrey’s Executor v. United States (1935). We all study that case for the proposition (contra Miers) that the President does not have absolute removal power over independent officers. But, writing for the Court, Justice Sutherland hints that there could be a problem with Congress creating the “quasi-legislative and quasi-judicial agencies,” but quickly dismisses it:

The authority of Congress, in creating quasi-legislative or quasi-judicial agencies, to require them to act in discharge of their duties independently of executive control cannot well be doubted; and that authority includes, as an appropriate incident, power to fix the period during which they shall continue in office, and to forbid their removal except for cause in the meantime.

While the case primarily rejected the President’s power to remove FTC Commissioners, it tacitly upheld the legality of these quasi-legislative and quasi-judicial chimeras. A holding that the latter were unconstitutional would have certainly meant the commissioners were purely-executive, and could be fired by the President.

Second, consider United States v. Curtiss-Wright (1936). In short, Congress passed a resolution that effectively gave the President the authority to decide how to craft a criminal statute that prohibited the sale of arms to countries the President determines:

‘Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That if the President finds that the prohibition of the sale of arms and munitions of war in the United States to those countries now engaged in armed conflict in the Chaco may contribute to the reestablishment of peace between those countries, and if after consultation with the governments of other American Republics and with their cooperation, as well as that of such other governments as he may deem necessary, he makes proclamation to that effect, it shall be unlawful to sell, except under such limitations and exceptions as the President prescribes, any arms or munitions of war in any place in the United States to the countries now engaged in that armed conflict, or to any person, company, or association acting in the interest of either country, until otherwise ordered by the President or by Congress.

Pursuant to this authority, President Roosevelt created a proclamation identifying Bolivia and Paraguay as the specified countries.

I do hereby admonish all citizens of the United States and every person to abstain from every violation of the provisions of the joint resolution above set forth, hereby made applicable to Bolivia and Paraguay, and I do hereby warn them that all violations of such provisions will be rigorously prosecuted.

Curtiss-Wright challenged the indictment in SDNY, and argued that the President could not prosecute him under the authority of the proclamation, as the joint resolution amounted to an unlawful delegation of the legislative power to the President. The SDNY judge agreed, and dismissed the indictment in part. For reasons I do not entirely understand, the case was appealed directly to the Supreme Court, and skipped the 2nd Circuit.

Writing for the Court, Justice Sutherland acknowledged that this issue is raised by the appeal, and explains that if the matter was of purely domestic law, there would indeed be a non-delegation doctrine problem (recall that he was writing for 8 Justices, Justice McReynolds dissenting).

The points urged in support of the demurrers were, first, that the joint resolution effects an invalid delegation of legislative power to the executive . . . . Whether, if the Joint Resolution had related solely to internal affairs it would be open to the challenge that it constituted an unlawful delegation of legislative power to the Executive, we find it unnecessary to determine. The whole aim of the resolution is to affect a situation entirely external to the United States, and falling within the category of foreign affairs. The determination which we are called to make, therefore, is whether the Joint Resolution, as applied to that situation, is vulnerable to attack under the rule that forbids a delegation of the law-making power. In other words, assuming (but not deciding) that the challenged delegation, if it were confined to internal affairs, would be invalid, may it nevertheless be sustained on the ground that its exclusive aim is to afford a remedy for a hurtful condition within foreign territory?

The Court avoided the issue, finding that the President did not need to rely on any delegation from Congress whatsoever. Rather, the President had the inherent authority pursuant to the Constitution. (The vitality of this holding is in serious doubt following Zivotofsky v. Kerry).

Third, in Hirabayashi v. United States (1943), the defendant asserted that the military curfew–promulgated by military officers acting on congressional statutes–violated the non-delegation doctrine.

The questions for our decision are whether the particular restriction violated, namely that all persons of Japanese ancestry residing in such an area be within their place of residence daily between the hours of 8:00 p.m. and 6:00 a.m., was adopted by the military commander in the exercise of an unconstitutional delegation by Congress of its legislative power, and whether the restriction unconstitutionally discriminated between citizens of Japanese ancestry and those of other ancestries in violation of the Fifth Amendment.

Chief Justice Stone emphatically rejected this argument:

What we have said also disposes of the contention that the curfew order involved an unlawful delegation by Congress of its legislative power. The mandate of the Constitution that all legislative power granted “shall be vested in Congress” has never been thought, even in the administration of civil affairs, to preclude Congress from resorting to the aid of executive or administrative officers in determining by findings whether the facts are such as to call for the application of previously adopted legislative standards or definitions of Congressional policy.

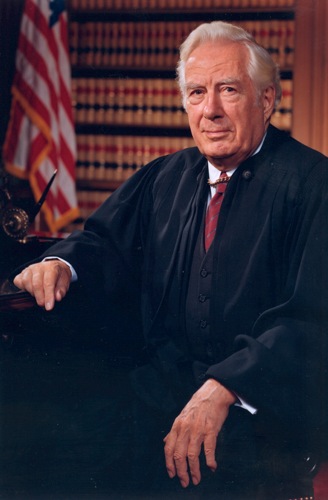

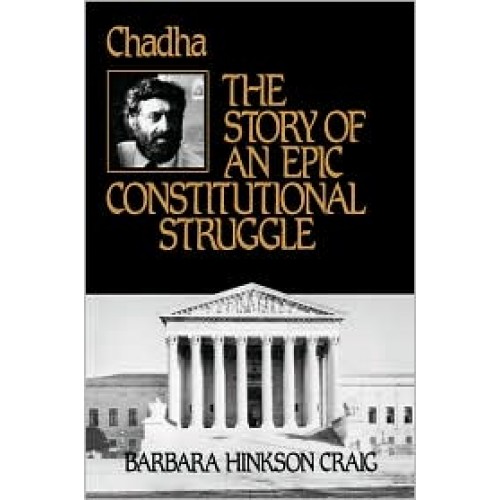

Fourth, INS v. Chadha (1983) considered the constitutionality of the so-called one-house veto. But antecedent to the one house veto, through the Immigration and Nationality Act, Congress delegated to the President the authority to decide not to remove specific individuals. One house of Congress could then override that decision, and force the executive to remove the individual. There are serious non-delegation doctrine problems here. Justice Powell acknowledges this in his concurring opinion:

Congress clearly views this procedure as essential to controlling the delegation of power to administrative agencies

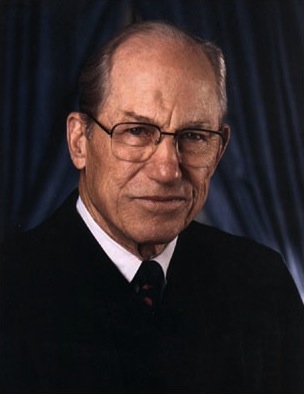

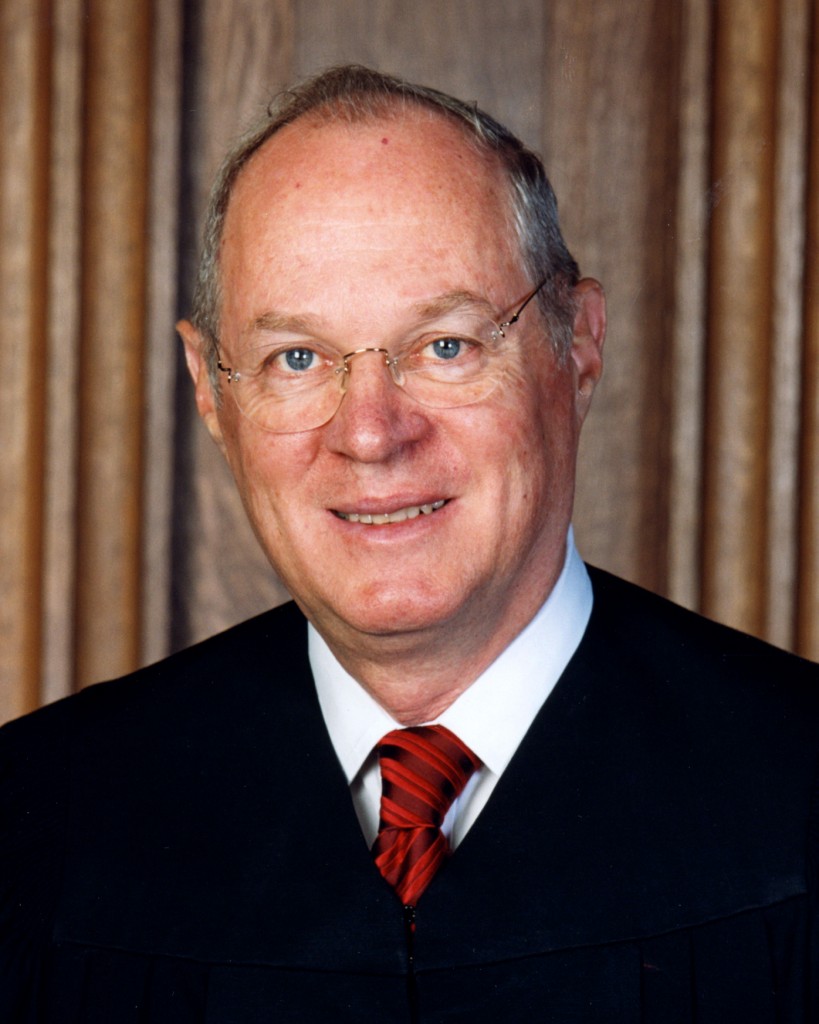

Congress is giving a legislative-type authority to the President to make exceptions to statutes. (We are far away from the “prosecutorial discretion” species of non-enforcement of today). Second, Congress has given itself the power to force the President to remove specific individuals, the quintessential executive prosecutorial power. (And, I might add a violation of the Bill of Attainder clause. Did you know that Circuit Judge Anthony M. Kennedy heard this case for the 9th Circuit, and found that the case also raised “serious bill of attainder and equal protection problems.”). The Court resolved Chadha on fairly narrow, bicameralism and presentment grounds, but the non-delegation doctrine was certainly lurking in the backdrop.

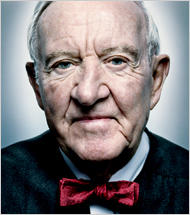

Finally, consider Clinton v. City of New York (1998). The line-item veto, much like the statute at issue in Chadha, gave the President the legislative-like power to amend statutes by choosing which ones to enforce. Like in Chadha, Justice Stevens resolves the case on the “narrow ground” based on the “finely wrought” procedure of of bicameralism and presentment. In Chadha, Congress didn’t comply with Art. I, Sec. 7 (only one house voted). In Clinton, the President didn’t comply withArt. I, Sec. 7 (his only options after presentment are to sign or veto–not cancel). Stevens acknowledges, but expressly rejects the non-delegation doctrine issue:

The excellent briefs filed by the parties and their amici curiae have provided us with valuable historical information that illuminates the delegation issue but does not really bear on the narrow issue that is dispositive of these cases. Thus, because we conclude that the Act’s cancellation provisions violate Article I, §7, of the Constitution, we find it unnecessary to consider the District Court’s alternative holding that the Act “impermissibly disrupts the balance of powers among the three branches of government.” 985 F. Supp., at 179

Justice Scalia’s dissenting opinion (which I go back and forth on) directly acknowledges the non-delegation doctrine.

As much as the Court goes on about Art. I, §7, therefore, that provision does not demand the result the Court reaches. It no more categorically prohibits the Executive reduction of congressional dispositions in the course of implementing statutes that authorize such reduction, than it categorically prohibits the Executive augmentation of congressional dispositions in the course of implementing statutes that authorize such augmentation–generally known as substantive rulemaking. There are, to be sure, limits upon the former just as there are limits upon the latter–and I am prepared to acknowledge that the limits upon the former may be much more severe. Those limits are established, however, not by some categorical prohibition of Art. I, §7, which our cases conclusively disprove, but by what has come to be known as the doctrine of unconstitutional delegation of legislative authority: When authorized Executive reduction or augmentation is allowed to go too far, it usurps the nondelegable function of Congress and violates the separation of powers.

Though the non-delegation doctrine is one life support, it isn’t dead. The Court always seems to recognize it, acknowledge it is uncomfortable with it, and then look the other way.