Even if President Trump manages to get his health reform through Congress, there is no guarantee it will survive the courts. Though the bill is still far from passage, the groundwork is already being laid to challenge its constitutionality. New York attorney general Eric Schneiderman has pledged to challenge the reductions in funding for reproductive-health services. Other Democrats have challenged the constitutionality of the bill’s Medicaid provisions. Some have suggested that the “lapsed coverage” surcharge for the uninsured might be unconstitutional.

If this bill is enacted — and that is a big if — opponents will locate every conceivable basis to contest the law, so it will be held up in litigation, potentially, until after the next election. While no one can predict how the Supreme Court will act, President Trump and Congress can take steps to minimize that uncertainty, and ensure a smoother implementation. As I argue in National Review, they can take a page out of President Clinton’s failed health-care reform, and channel all litigation through a single three-judge panel, with a direct appeal to the Supreme Court. This approach would, as a Clinton-administration official noted two decades ago, bring “swift answers to the general constitutional challenges to the plan.”

Today, virtually all federal constitutional litigation begins before a single district-court judge, with an appeal to a three-judge panel. However, for much of the 20th century, Congress let litigants cut to the chase. Under the Three-Judge Court Act of 1910 and other contemporary bills, constitutional challenges would begin before a three-judge panel. As the practice developed, each panel would consist of two district-court judges and a single appeals-court judge. Within this framework, litigants would bypass any intermediate review, and there would be a mandatory review by the Supreme Court. In 1976, however, Congress severely curtailed their usage, retaining them only for challenges to apportionment maps.

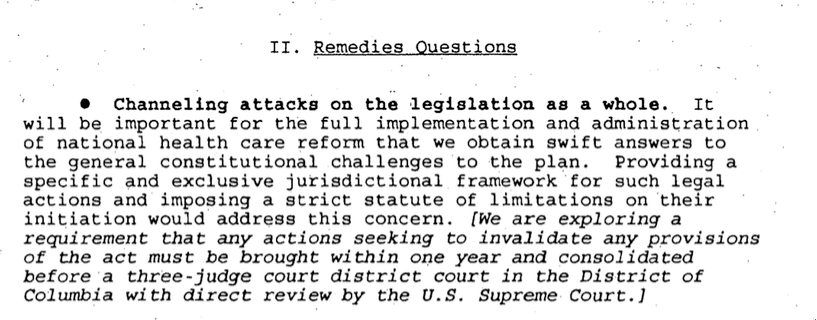

This approach nearly made a comeback two decades later. In September 1993, the New York Times reported that the Clinton administration was “just beginning to understand the potential wave of legal challenges” to its soon-to-be introduced health-care bill. Walter Dellinger, who headed the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, wrote that the Times article was “unnecessarily alarming.” Indeed, the executive branch had already prepared a plan for “channeling attacks on the legislation as a whole” through a narrow path to the Supreme Court. Specifically, the bill would reinvigorate the old model.

…

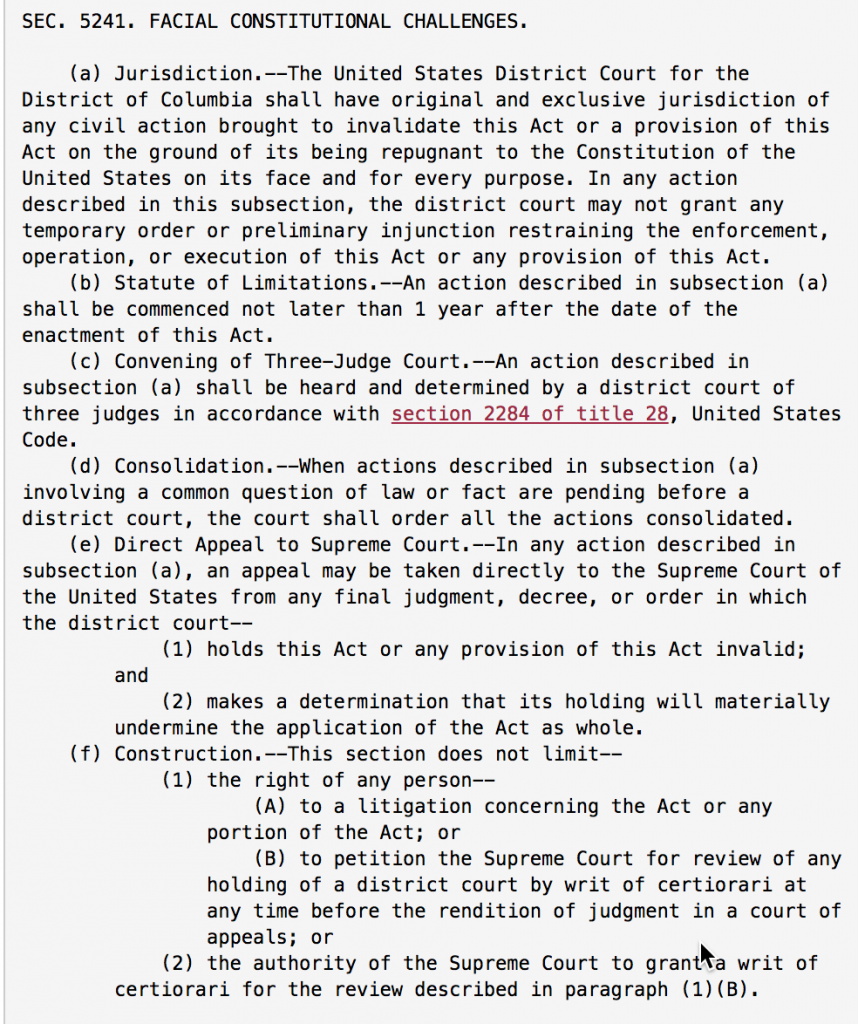

Constitutional challenges to the Health Security Act could be filed only in the federal court in the District of Columbia (Section 5241). Critically, this three-judge panel would not be able to issue nationwide injunctions that halted the implementation of the law. Moreover, all challenges to the law from the country would have been consolidated before the same jurists, and must be filed within one year. After the initial trio ruled, the case would be appealed directly to the high court. This approach allowed a quick, seamless review of the bill, which ensured a smooth implementation during that process.

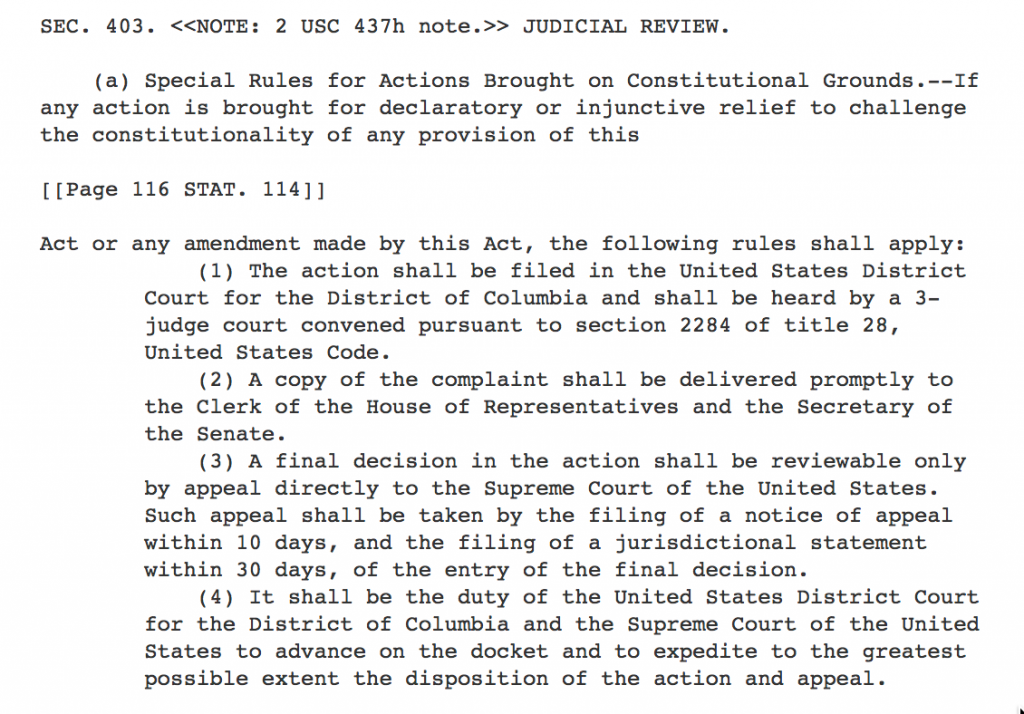

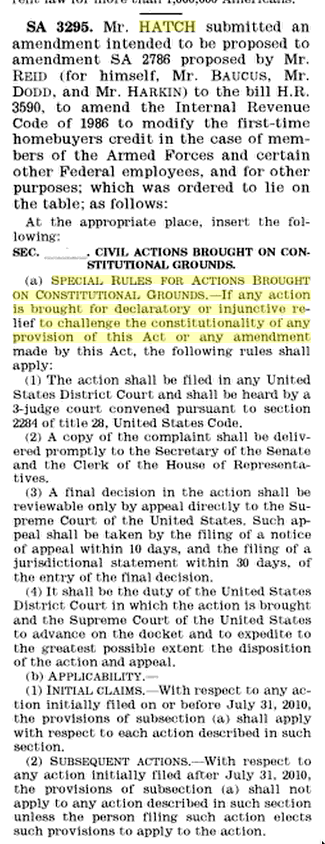

A decade later, the McCain-Feingold Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act employed a similar review process (Section 403), which urged the Supreme Court to “expedite [the appeal] to the greatest possible extent.”

Republicans should adopt the same amendment that was developed by the Clinton administration two decades ago: channel all constitutional challenges to the health-care bill to a three-judge panel, with a mandatory appeal to the Supreme Court. This approach would have three primary benefits. First, consolidating the appeals would eliminate duplicative, time-consuming, and expensive litigation. (These cost savings could allow such an amendment to survive the rules of the budget-reconciliation process.) During debates over the Affordable Care Act in 2009, Senate Democrats rejected a proposed amendment that would have allowed an expedited review of that health-care legislation.

As a result of this decision, more than a dozen separate constitutional challenges were litigated in parallel for two years until the Supreme Court interceded. Regardless of what those lower courts did, the case would have ultimately wound its way to the terminus: With the vote of Chief Justice Roberts, the health-care law survived constitutional scrutiny.

Second, restricting the jurisdiction to a three-judge panel would eliminate the latest fad in federal litigation: the nationwide injunction. As illustrated with the travel-ban litigation, when different courts issue different injunctions with different scopes, there is often widespread confusion about what the state of the law is at any given time. Under this proposal, the three-judge panel could quickly resolve any constitutional questions, and allow the Supreme Court to opine on it. Preliminary injunctions, before a final resolution, would be unnecessary.

Third, this approach would eliminate the incentives for forum shopping. It is no coincidence that the constitutional challenges to President Trump’s executive actions have been filed in federal courts with a majority of Democratic-appointed jurists. Rather than dealing with dueling decisions from Hawaii, Seattle, or Brooklyn, litigants under this plan would face only judges in the District of Columbia. (In a twist of fate, the role of appointing two out of the three judges on the panel would fall to none other than Merrick B. Garland, the chief judge of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals.) The final call will be made by the Supreme Court — and it is better that we have the answer sooner, rather than later.