I have submitted grades for Constitutional Law. You can download the exam question, and the A+ paper (If this is yours, please drop me a line!).

This was an extremely difficult test, by design, because I had high expectations. For the most part, you met those expectations. Here is the breakdown of the grades. On the whole, the grades were quite good, and I am very proud of the class. The students who scored below a C- were unable to finish, and left portions of the exam blank.

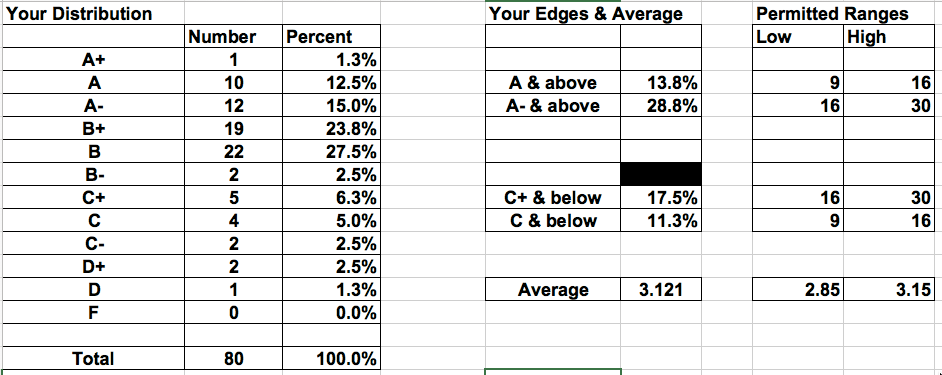

Here is the final exam distribution, which was on the upper-end of grades A- and above, and on the lower ends of grades C+ and below.

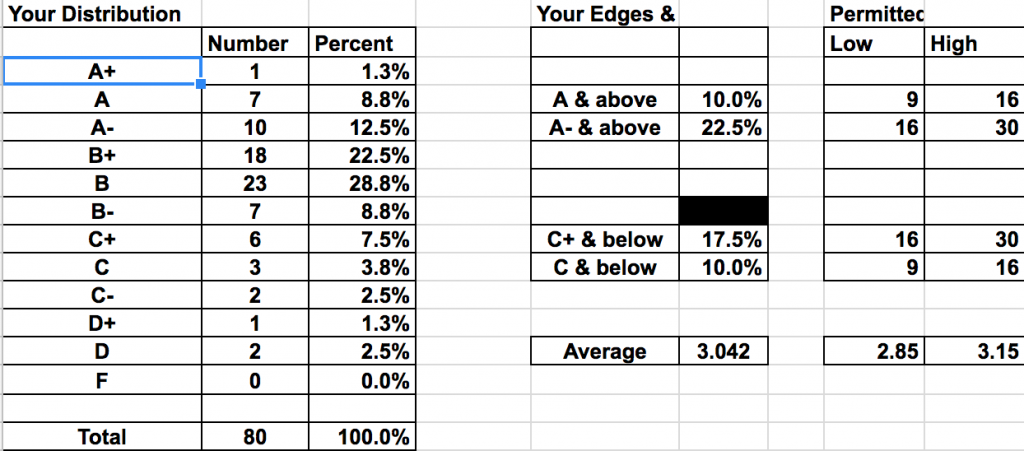

The mean of 3.121 is a stark improvement from the midterm, which had an average of 3.042:

I would like to provide some high-level thoughts on each question.

Part I

This question was premised on a hypothetical raised by one of your classmates during the final week of class: could Congress criminalize the live-streaming of a murder. When I asked the class what you all thought, on one raised their hands. That was my cue to make it an exam question, with a twist. Instead of live-streaming a murder, here, Bert & Ernie (fraternal twins, separated at birth, who were married), committed a sex act on the internet. This question involved laws by both Texas and Congress, criminalizing the act of incest itself, and the broadcast of sex acts. As the A+ paper noted in the very first sentence, “Awkward.”

1. The first question asked you to assess the constitutionality of TRICK (Texans Reject Incestuous Couples because won’t somebody please think of the Kids) under the 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause. The critical issue here was whether the Court’s gay-rights precedents (Lawrence, Windsor, and Obergefell) should be extended to protect consensual, adult incest. Specifically, was “moral disapproval” a valid state interest. The best papers compared and contrasted sodomy from incest, and explained why the protections should or should not be extended. One wrinkle: because two males were at issue, who could not reproduce, concerns about hereditary defects were simply inapplicable. (Conversely, heterosexual couples who both have recessive genes are allowed to reproduce without the government’s concerns).

2. The second question asked you to assess the constitutionality of SIBLING (Scrutinizing Internet Broadcasts because Livestreamed Incest is Not Good) under the 1st Amendment’s free speech clause. Many of you jumped the gun and talked about due process here. That was the prompt for question #3. It is not only important to read the question, but the fact pattern. Even though the title of the bill had the word “livestream” in it, the actual text of the bill only prohibited the recording of the incest act. Here, the case was distinguished from the crush films at issue in United States v. Stevens. Can Congress criminalize the mere recording of a consensual sex act? This raised the question of obscenity, and in particular the Miller test, and Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition.

3. Here you have to assess SIBLING under the 5th Amendment’s due process clause (because we are talking about a federal law). Unlike question 2, here you had to discuss the legality of a law that criminalizes the recording of a sex act between biological brothers and sisters. Unlike question 1, it was not enough to say that there is a due process right to engage in sex. The issue involves the broader recording of the act. Beyond that distinction, cases like Lawrence should also be cited here. Many students picked up on the fact that the law only applies to biological brothers and sisters, and not parents and children. In terms of narrow tailoring, this under-inclusiveness suggests the law was enacted to directly target Bert and Ernie.

4. Congress’s authority to enact SIBLING must be derived, if at all, from a combination of the Commerce and Necessary and Proper Clauses. Again, because the law applied only to the recording, and not transmission of the sex acts, there is not a clear exercise of interstate commerce. Further, is recording, without a “jurisdictional hook” an economic activity under Lopez/Morrison. If it is economic activity, does it have a substantial effect of interstate commerce (Wickard/Raich)? If not, can this be seen as part of a comprehensive regulatory scheme (Scalia in Raich)? If so, is it both necessary and proper to intrude on fundamental rights (NFIB). This question had many layers.

5. The final part asked you to consider how the courts should consider laws premised on “moral disapproval” and traditional notions of morality. Did Windsor and Obergefell eliminate these grounds as possible rational bases for laws? Can incest laws survive after Obergefell?

Part II

The second question represented my best effort to interject present-day conflicts into a time in our past: in response to the Zimmerman Telegram, the Governor of Texas plans to build a wall on the southern border to repel a threatened Mexican invasion, but in a “tweet,” admits the true purpose is to stem the flow of migrant workers. These fact patterns write themselves! (I muss confess to a slight alteration of historical accuracy, as Governor Hobby was elected a few months after the Zimmerman Telegram was sent; his wife did attend South Texas College of Law).

1. In response to Governor Hobby’s wall-building plan, Congress and President Wilson enacted ONCE (Only Congress Can Exclude Act of 1917 ). (In another deviation from history, Governor Hobby was in fact a strong supporter of President Wilson). Section 2 of the bill prevent state executive-branch officials from building a wall. This provision implicates the commandeering doctrine, though we are eight decades before Printz v. United States. However, the basis of Printz was still available: the necessary and proper clause. Specifically, was it proper for Congress to tell the Governor what to do. But then was the Governor ordered to do anything, or simply stop doing anything. This question was heightened by the fact that foreign policy was implicated, an area where the states are subordinate to the federal government. Also relevant was the preemption doctrine, and M’Culloch v. Maryland, as Congress was trying to supplant state law that conflicted with federal law.

2. Section 3 of once, which prohibited state judges from assisting with the construction of the wall, yielded a different answer than the previous question. Under the supremacy clause “state judges” are in fact bound by federal law. Justice Scalia made this distinction in Printz, but it can be derived directly from Article VI. Even if you drew this conclusion, you still have to decide whether presiding over an eminent domain proceeding amounts to assisting with the construction of the wall. Also, does the court have jurisdiction if a federal law preempts the state statute. (As an aside, here Judge Andy in Brownsville was an homage to U.S. District Judge Andy Hanen who sits in Brownsville; also, this property professor enjoyed labelling the ranch Blackacre).

3. The third question asked you to consider Texas’s draft under both the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment and the First Amendment’s Free Exercise Clause, as applied to a Pacifist quaker who did not want to serve in the national guard. With respect to the Due Process Clause, the leading case I was thinking of, that no one cited, was Jacobson v. Massachusetts, which involved compulsory vaccination. Some years later, Justice Holmes cited Jacobson in Buck v. Bell, and said if the government can force you to be vaccinated, and serve in the military, then it can sterilize you. Also relevant was Lochner and the early substantive due process cases. Some students wrote about Slaughterhouse and liberty of contract–that is, the pacifist was being forced to work for the government, and could not negotiate his wages. The Free Exercise claim was much tougher, because I did not want you to rely on modern cases. (Here the A+ paper erred). A leading authority that we studied was Madison’s Memorial and Remonstrance.

4. The fourth question asked you to consider a law requiring public school students, without exception, to pledge allegiance to the Texas flag. I deliberately modified the Texas pledge to omit any reference to God, to avoid any free exercise of establishment clause issues. Again, in 1917, there was not much free speech jurisprudence to go with. Some students discussed the experiences of the alien and sedition act, which were very much on point.

5. The final question asked to what extent courts should consider the Governor’s subjective motivations, as reflected in his “tweet” (message sent by a carrier pigeon named Tweet). Here, Yick Wo and Lochner were directly on point. In the former case, the Court searched for the “evil eye” behind facially neutral legislation. In the latter, the Court second-guessed New York’s determinations of what is actually required for public safety. Many students incorporated the Baptist and Bootlegger analysis, which was very good.

—

On the whole, I was very proud. Well done.