Then Roberts offered a mild criticism of how the law itself was enacted: “The Affordable Care Act contains more than a few examples of inartful drafting.” Mark Walsh recalled that “many in the Courtroom snicker[ ed]” at this jab, but there were no members of Congress in attendance “to receive this scolding in person.” Roberts explained that “[s]everal features of the Act’s passage contributed to the unfortunate reality of its, to be charitable, ‘imprecision.’” The phrases “charitable” and “imprecision” did not make it into Roberts’s written opinion.

“Congress wrote key parts of the Act behind closed doors,” the chief said, “rather than through the traditional legislative process.” Further, “Congress passed much of the Act using a complicated budgetary procedure known as Reconciliation, which limited opportunities for debate and amendment and bypassed the Senate’s normal 60 vote filibuster requirement.” This was a not-too-subtle reference to the disjointed manner in which the draft Senate bill became the final bill because of Scott Brown’s election. “As a result, the Act does not reflect the type of care and deliberation that one might expect of such significant legislation.” Roberts referenced a “cartoon that Justice Frankfurter once quoted in which a senator told his colleagues that a new bill was too complicated to understand and that they would just have to pass it to find out what it means.” Roberts must have realized the irony that then-Speaker Nancy Pelosi famously said of the ACA, “But we have to pass the bill so that you can find out what’s in it.” 5 In Roberts’s mind, the enactment of the ACA was a caricature of a cartoon.

This lack of bipartisanship [to enact the ACA] was unprecedented. All of the landmark social welfare and civil rights laws enacted in the twentieth century were passed with bipartisan support, often through messy political compromises and bargaining. The Social Security Act of 1935 was supported by 77 Republicans in the House, joined by 288 Democrats. In the Senate, 15 Republicans joined 60 Democrats. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed the Senate because of a coalition of 27 Republicans and 44 Democrats united to break a segregationist-led filibuster. The Social Security Amendments of 1965, which created Medicaid and Medicare, passed the House by a vote of 307– 116, with 70 Republicans voting in favor. This monumental health care legislation cleared the Senate by a vote of 70– 24; 13 Republicans crossed the aisle. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 was passed with broad bipartisan support, as was the Civil Rights Act of 1968. In 1990, the Americans with Disabilities Act passed with 90% agreement in the House and Senate.

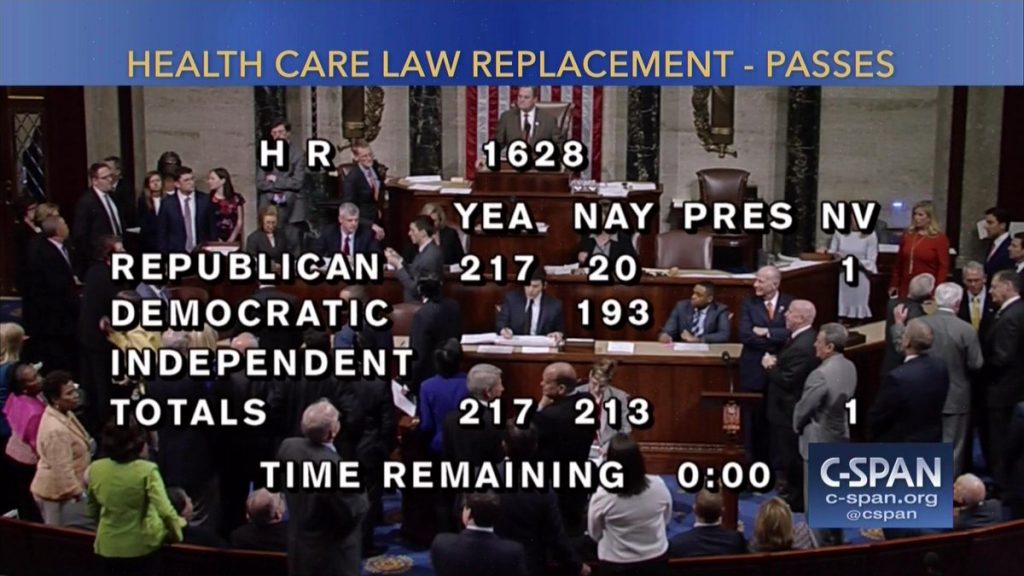

Update: The American Health Care Act has passed the House by a vote of 217-213. Not a single Democrat supported the bill, 20 Republicans voted against it, and 1 Republican abstained.

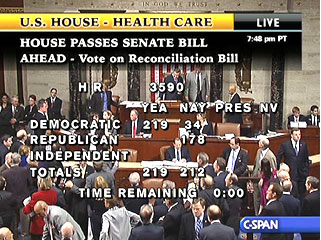

Contrast this roll call with the House’s vote to approve the Affordable Care Act in March 2010. The final vote was 219-212. Thirty-four Democrats voted against the bill, and zero Republicans supported it.

And, to draw one more contrast, consider this member’s defense of passing a bill that he did not read:

“Oh, gosh!” Rep. Thomas Garrett (R-Va.), another Freedom Caucus member, elected in 2016, said in an interview with MSNBC. “Let’s put it this way: People in my office have read all the parts of the bill. I don’t think any individual has read the whole bill. That’s why we have staff.”

Fortunately, none of the details in the House bill will matter because the Senate is starting from scratch (as I expected all along).

Senate Republicans said Thursday they won’t vote on the House-passed bill to repeal and replace Obamacare, but will write their own legislation instead.

A Senate proposal is now being developed by a 12-member working group. It will attempt to incorporate elements of the House bill, senators said, but will not take up the House bill as a starting point and change it through the amendment process.

“The safest thing to say is there will be a Senate bill, but it will look at what the House has done and see how much of that we can incorporate in a product that works for us in reconciliation,” said Sen. Roy Blunt, R-Mo.

“We are going to draft a Senate bill,” added Sen. Chuck Grassley, R-Iowa. “That is what I’ve been told.”

The working group has been meeting for weeks, said Senate Majority Whip John Cornyn, R-Texas, a member of the group.

“What we have to do is build a consensus among our conference and that is what the working group is designed to do,” Cornyn said. “To get to a compromise we can agree to and then present it to the larger conference.”

Cornyn said there is “really no deadline” for the group to produce a bill. “We are just working toward getting 51 votes,” he said.

The entire purpose of this House vote was to get the ball rolling on the reconciliation process, and let the Senate do the heavy lifting.