Cross-Posted at Volokh Conspiracy.

After six years of pitched political battle, it has become conventional wisdom that Republicans are responsible for the Affordable Care Act’s unraveling. In part, this is true. Specifically, the refusal of red-states to enter the Medicaid expansion, and the defunding of the “risk corridors” have limited the law’s success. However, many of Obamacare’s deepest wounds have been self-inflicted. Out of desperation to ensure as many people as possible signed up for health insurance, the Obama administration has arbitrarily suspended onerous mandates, modified coverage requirements, and extended enrollment periods. These illegal, ad hoc changes to the ACA–which I’ve referred to as “government by blog post“–have unintentionally, but foreseeably weakened the exchanges during the pivotal first three years.

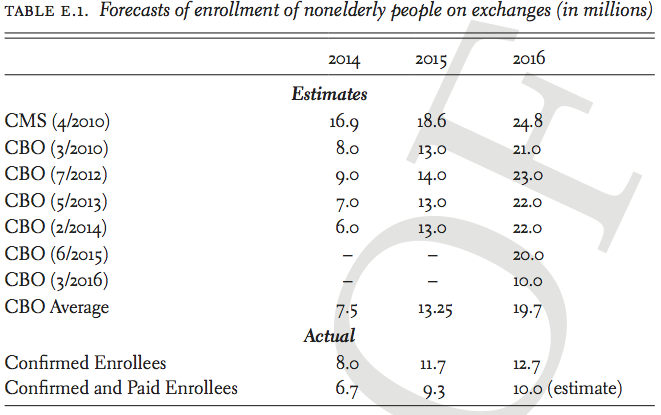

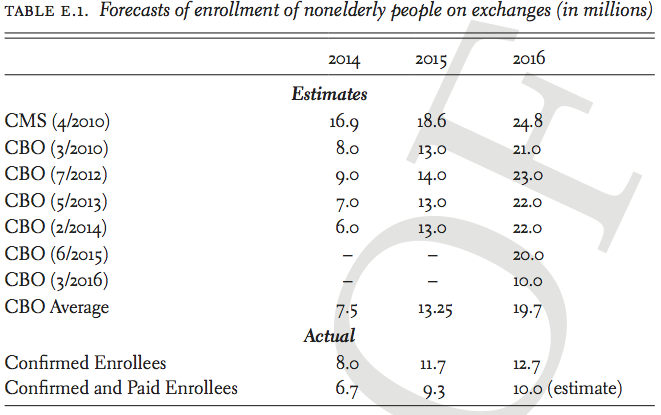

The leading measure of the ACA’s success is the number of people who have enrolled on the exchanges. This table, from the epilogue of Unraveled, illustrates how the law has fallen far short of its great expectations.

In 2014, Obamacare met the CBO’s original goal from 2010, with 8 million enrollments. This was truly a red-letter year for the ACA, demonstrating that there was strong demand for the exchange policies. After 2014, however, the demand has leveled off. In 2015, there were 11.7 million enrollments, far fewer than the CBO’s average forecast of 13.25 million. From 2010 through 2015, CBO consistently predicted that enrollments would spike up in 2016, with 20–24 million enrollments. For example, in its February 2014 report, CBO wrote that “more people are expected to respond to the new coverage options, so enrollment is projected to increase sharply in 2015 and 2016.” The surge never happened. In March 2016, CBO drastically downgraded its forecast by half to 10 million enrollees. As of July 2016, there have been 12.7 million confirmed enrollees on the exchange – beating the revised 10 million figure, but falling significantly short of the expected 20 million. The ACA’s expansion of coverage to 20 million Americans is still far short of even its most conservative estimate of more than 30 million Americans gaining coverage.

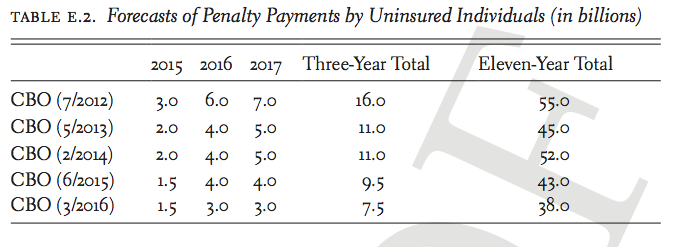

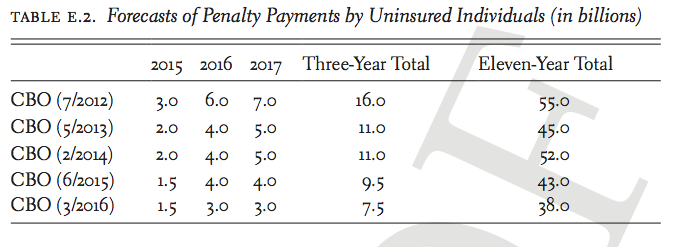

Another measure of the ACA’s success is quantifying how many people have payed the individual mandate penalty. That is, qualified individuals who do not carry “minimum essential coverage” are obligated to pay an income-adjusted-penalty. The purpose of the penalty, as the government explained to the Supreme Court in NFIB v. Sebelius, was to prevent people from free-riding on the provision of the law that guarantees issuance of policies to everyone, regardless of pre-existing conditions.

Like the exchange enrollment numbers, the collected penalty revenue has lagged far behind original estimates.

There is an incongruence to these forecasts. The number of people who have gained coverage on the ACA exchange is far fewer than originally forecasted: 10 million instead of 20 million. As a result, more people who otherwise would have obtained coverage, should now be subject to the mandate’s penalty. The revenue should be far greater than originally predicted. But the exact opposite happened.

This shortfall can be explained by two executive actions taken by the Obama administration, which allowed people to avoid purchasing qualified insurance, without having to pay the individual mandate’s penalty.

The Administrative Fix

The first such executive action is known as the “administrative fix.” President Obama promised nearly three-dozen times that “if you like your plan, you can keep your plan.” Of course, this was a promise that could never be kept. Due to strict grandfathering regulations promulgated by the Obama administration, insurers cancelled policies that did not provide “essential coverage.” During the fall of 2013, as millions of Americans received cancellation notices, the President’s oft-stated promise crumbled. In response, in November 2013 he announced an executive action that came to be know as the “administrative fix.” To grossly oversimplify, the federal government would not enforce the individual mandate’s penalty against individuals who continued to carry these policies that would otherwise be void. The policy gave states, and ultimately the insurers, the choice of whether to continue selling these policies. I’ve argued elsewhere that this fix was unlawful, but most relevant for our purposes is how it impacted the vitality of the exchanges.

There were risks to allowing people to remain on old plans. Jim Donelon, Louisiana Insurance Commissioner, warned that the administration’s decision “threatens to undermine the new market, and may lead to higher premiums and market disruptions in 2014 and beyond.”Extending the grandfathering of noncompliant plans,” health care industry consultant Robert Laszewski observed, “tends to undermine the sustainability of Obamacare” because it reduces incentives for customers to purchase policies on the exchanges. And more likely than not, these grandfathered customers are younger and healthier, because they were able to obtain insurance even before the ACA’s guaranteed-issue requirement kicked in.

Moody’s Investor Service forecasted that the administrative exemption would result in “exposure to adverse selection” and was “likely to negatively affect earnings in 2014.” In June 2014, the Congressional Budget Office wrote that its downward forecast for penalty payments was due “in part to regulations issued since September 2012 by the Departments of Health and Human Services and the Treasury.” As a result, there is “an increase in [its] projection of the number of people who will be exempt from the penalty.” According to the IRS Commissioner John Koskinen, 12.4 million taxpayers claimed an exemption from the mandate for 2014. Koskinen explained that many tax-payers claimed an exemption because “health care coverage [was] considered unaffordable.” This is not one of the exemptions carved out by Congress in the ACA. Rather, this was a consequence of the president’s executive action, which waived the individual mandate’s penalty for taxpayers who told the government that a new policy was too expensive.

The fix was originally slated to provide temporary relief for one year. However, that would have resulted in millions of plans being cancelled in the fall of 2014, on the eve of the midterm elections. The president would not let that happen. HHS announced that noncompliant plans could be grandfathered through the end of 2016. Insurers were now able to renew noncompliant policies as late as October 1, 2016, so coverage could continue past the next presidential election into 2017. The New York Times observed this action “essentially stall[s] for two more years one of the central tenets of the much- debated law, which was supposed to eliminate what White House officials called substandard insurance and junk policies.”

By exempting millions of Americans from the individual mandate, the Obama administration disturbed the fragile balance Congress designed to prevent an adverse selection death spiral.

Special Enrollment Periods

As weak as these enrollment numbers are, the actual numbers of customers who continued to pay for their policies for nine consecutive months is even lower. In 2014, only 6.7 million out of 8 million enrollees paid their premiums through September. This 19% drop-off puts the 2014 figures well below the CBO forecasts. In 2015, only 9.3 million out of the 11.7 million paid their premiums through September. Over 25% of enrollees failed to consistently pay their bills. In 2016, only 11.1 million out of 12.7 million paid their premiums through March, with an expected 10 million to continue paying through September. Factoring in customers who actually continue to pay for coverage, the state and federal risk pools are barely at 50% of their anticipated size.

Savvy shoppers have learned to game the system: They sign up, receive treatment, and cancel coverage. The ACA was designed to restrict enrollment for specific times to frustrate this opportunism. In 2009, CBO wrote that in addition to the individual mandate, the ACA’s “annual open enrollment period” would tend to mitigate … adverse selection.” In his brief to the Supreme Court, the Solicitor General explained that restricting enrollment to a fixed period “would reduce opportunities for healthy people to wait until illness struck before enrolling.”

However, in a desperate effort to boost raw enrollment numbers, the Obama administration consistently delayed signup deadlines through an ad hoc series of changes. According to The New York Times, HHS created more than thirty “special enrollment” windows, many of which were only mentioned in “informal ‘guidance documents.’” For example, customers were allowed to sign up late due to unspecified “exceptional circumstances,” “serious medical condition[s],” and – the most capacious standard – “other situations determined appropriate” by HHS.

The National Association of Insurance Commissioners complained that “consumers are not required to provide documentation to substantiate their eligibility for a special enrollment period.” Kaiser Permanent, a large health insurer, said that the potential for abuse “poses a significant threat to the affordability of coverage, and to the viability” of the exchanges. In 2016, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) concluded that HHS “has assumed a passive approach to identifying and preventing fraud.” The agency’s honor system policy “allowed an unknown number of applicants to retain coverage, including subsidies, they might otherwise have lost, thus producing higher costs for the federal government.”

Leading insurance companies submitted regulatory comments to HHS, warning that the extra signup windows risked destabilizing the insurance markets. Blue Cross Blue Shield explained that “individuals enrolled through special enrollment periods are utilizing up to 55 percent more services than their open enrollment counterparts.” Aetna added that “many individuals have no incentive to enroll in coverage during open enrollment, but can wait until they are sick or need services before enrolling and drop coverage immediately after receiving services … less than four months” later. United Healthcare, which will exit from most of the Obamacare exchanges in 2017, explained that more than 20% of its customers signed up during a special enrollment period, and they used 20% more health care than those who enrolled during the regular enrollment period.44 Anthem told the government that these modifications of the deadlines were “harming the stability of the exchange market and resulting in higher premiums.” The Obama administration’s sign-up-as- many-people-as-possible approach has eliminated one of the key constraints embedded in the ACA and reduced the force of the individual mandate.

During the exchange’s first three years, due to these sorts of ad hoc, regulatory changes, the ACA suffered from severe self-inflicted wounds. The Obama administration has recently announced that it was tightening up the special enrollment periods. Additionally, in 2017 the administrative fix expires. Plus certain measures designed to cushion the exchange’s birth–what is know as reinsurance and risk corridor also wind down in 2017. At that point, the full brunt of the ACA’s mandates will be faced.

—

Josh Blackman is a constitutional law professor at the Houston College of Law, and the author of Unraveled: Obamacare, Religious Liberty, and Executive Power (Cambridge University Press, 2016).