An advisor to Hillay Clinton said that Heller was “wrongly decided.” But she has absolutely no idea what the case held.

“Clinton believes Heller was wrongly decided in that cities and states should have the power to craft common sense laws to keep their residents safe, like safe storage laws to prevent toddlers from accessing guns,” Maya Harris, a policy adviser to Clinton, said in an e-mailed statement. “In overturning Washington D.C.’s safe storage law, Clinton worries that Heller may open the door to overturning thoughtful, common sense safety measures in the future.”

The critical, constitutional issue, was whether the District of Columbia could ban the private ownership of handguns. The case in no way affected “safe storage laws.” In fact, the District of Columbia still has safe storage laws in effect.

From the Metropolitan Police Department’s website:

The law requires that no person shall store or keep any loaded firearm on any premises under his control if he knows or reasonably should know that a minor under the age of 18 is likely to gain access to the firearm without the permission of the parent or guardian of the minor unless such person . . . Keeps the firearm in a securely locked box, secured container, or in a location which a reasonable person would believe to be secure.

If Ms. Harris is going to criticize a Supreme Court decision, she should have some clue what the case is about.

(I have my doubts about whether such a law is in fact constitutional, but Heller in no way affected such a law).

Update: In Heller, the Court also considered the constitutionality of the D.C. trigger-lock law. This is different from a “safe storage law.” The Heller Court described the law in this fashion:

District of Columbia law also requires residents to keep their lawfully owned firearms, such as registered long guns, “unloaded and dissembled or

bound by a trigger lock or similar device” unless they are located in a place of business or are being used for lawful recreational activities.

Under safe-storage laws, guns are to remain operable, but must remain in a secured case or box.

At the time, the only guns that could lawfully be owned in D.C. were certain long guns, or handguns that were owned before the ban went into effect.

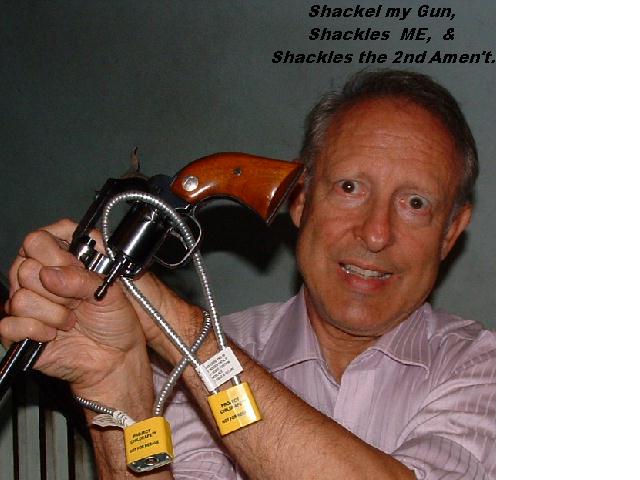

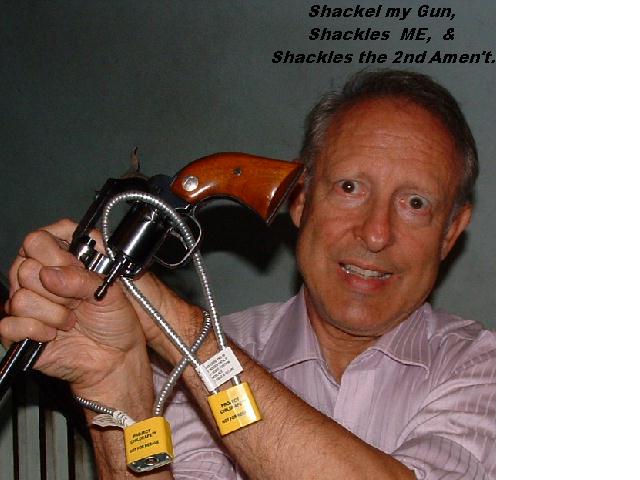

For example, Dick Heller owned a firearm from the 1970s, but was not allowed to remove the locks. The instant he removed the lock–even if it were for self-defense–he would have broken the District of Columbia’s law.

Even assuming that Harris simply used the wrong term, her answer lets on more than she would like.To say that the problem with Heller was that it invalidated some sort of safe-storage law, presupposes that a resident of the District of Columbia had a constitutional right to own a gun in the first place. If you adopt the dissent’s view, D.C. could have banned ownership of handguns all-together. The storage law was an added benefit.