My Lex Predict colleagues Daniel Katz and Mike Bommarito, along with Tyler Soellinger and James Chen, have published a fascinating study of how securities markets react to the Supreme Court. The authors find:

Across all cases decided by the Supreme Court of the United States between the 1999-2013 terms, we identify 79 cases where the share price of one or more publicly traded company moved in direct response to a Supreme Court decision. In the aggregate, over fifteen years, Supreme Court decisions were responsible for more than 140 billion dollars in absolute changes in wealth.

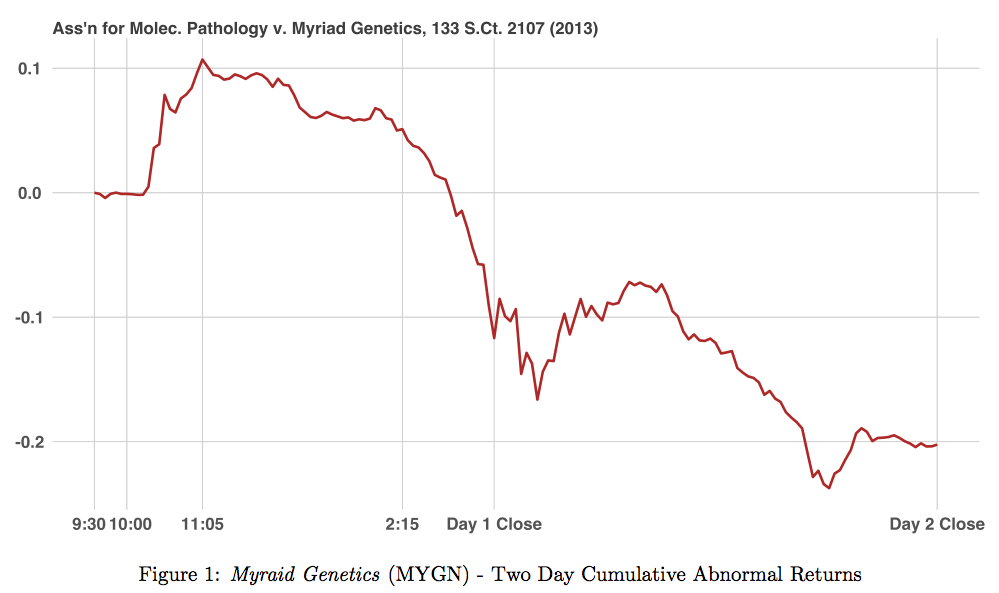

For example, here is the graph showing the abnormal returns in the stock for Myriad Genetics, before and after the Supreme Court’s complicated decision at 10:00.

You can see the spike right after 10:00 when the decision was released.The authors explain:

As displayed in Figure 1, the Court’s compromise decision initially confused the equity market. Fueled in part by media reports, would-be arbitrageurs interpreted the Court’s decision as positive to Myriad in the initial hours of trading. However, this view was ultimately displaced as more careful reading and subsequent understanding revealed that the decision was highly unfavorable to Myriad’s business interests. As a result, the stock began to trade down in the second half of the session. Media coverage following the initial trading day called it a “wild ride” and a “market whipsaw.”

As the dust settled, the Court’s decision was indeed detrimental to Myriad’s long-term financial value. Even after controlling for overall market trends, Myriad’s stock lost in excess of 20% of value over the two-day trading window. Attendant to this change in price, there was also a significant increase in volume as traders sought to shift their positions in light the Court’s decision. Specifically, on the date of decision, there was roughly a thirteen-fold increase in trading volume of the stock. The day thereafter witnessed an eighteen-fold increase in trading volume.

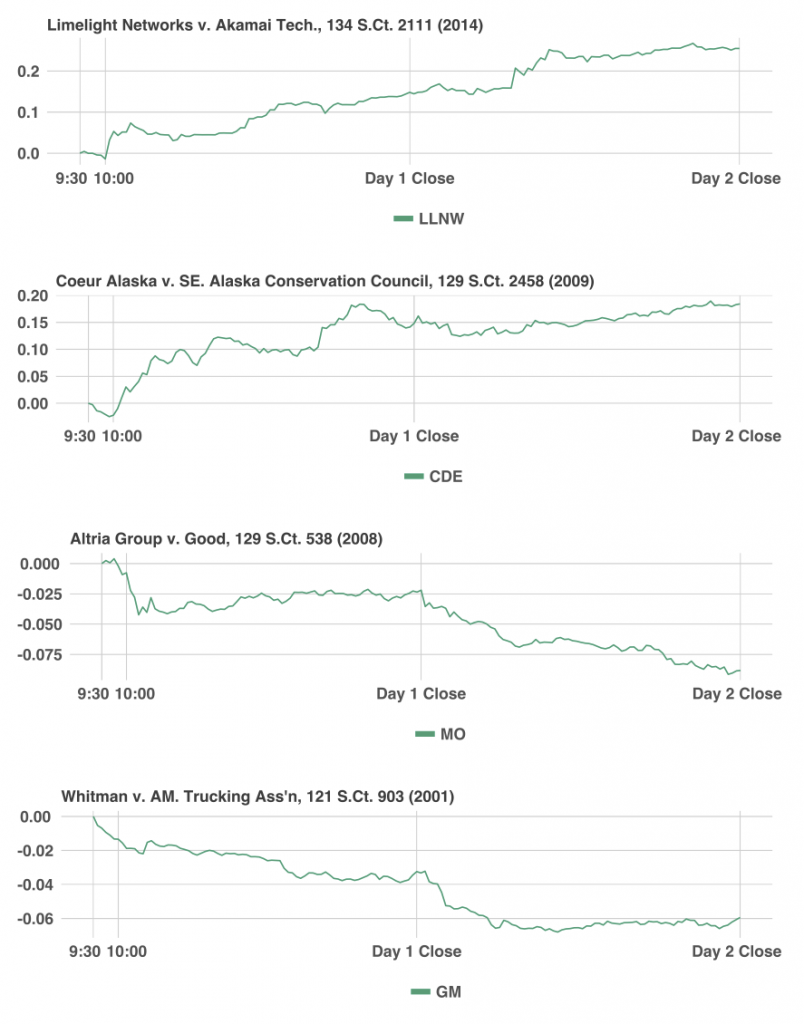

The article also highlights a number of SCOTUS decisions that yielded statistically significant movements on the market. For examples, these graphs illustrate what happened after 10:00 in four cases:

- Limelight Networks v. Akamai (2014): The Court held the answer was no and that decision was highly beneficial to Limelight Networks (LLNW). As displayed in Figure 5, the stock experienced an almost immediate gain of 5%, finishing the day up nearly 15%. The second day of trading saw LLNW continue to steadily rise into the afternoon of the session.

- Coeur Alaska v. SE Alaska Conservation Council (2009): “As displayed in Figure 5, within hours, the Coeur stock (CDE) traded up 10% and finished the day by posting S&P adjusted cumu- lative abnormal returns around 15%. The following day saw some small additional gains, but most of the returns had been established in the first trading day. “

- Altria Group v. Good (2008): “As displayed in Figure 5, following this Court announcement, Altria’s (MO) stock immediately trended down, followed by lateral trading for much of the balance of the date of decision. In the following day, Altria’s continued to decline relative to the S&P as the financial implications of the Court’s decision began to become more widely understood. Ultimately, at the close of the two-day window, the stock had experienced a negative cumulative abnormal return of nearly 9%. “

- Whitman v. American Trucking (2001): “While the Court’s decision was somewhat mixed, Figure 5 reveals what appears to be a clear negative market reaction to the Court’s decision. The then largest automaker General Motors (GM) traded down over the next two sessions.13 ”

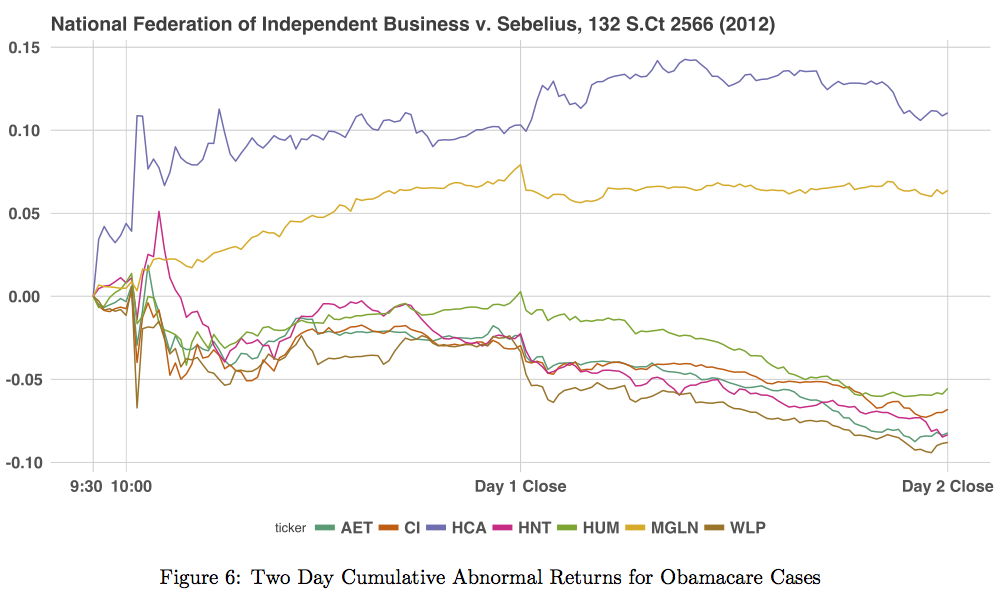

The portion of the paper that hits closest to home studies the impact of NFIB v. Sebelius on the leading healthcare companies:

Fascinatingly, the insurance companies surged during the initial reporting that the Court invalidated the mandate. (This counters the conventional wisdom that the insurance companies are happy with Obamacare…). But when everything settled, and everyone realized what happened, the insurance stocks tumbled. The only stocks that continued to grow was Hospital Corporation of America and Magellan Health Services. Aetna, Cigna, Humana, and Anthem all fell.

In Figure 6, we plot cumulative abnormal returns for a significant number of healthcare related stocks including Aetna (AET), Cigna (CI), Hospital Corporation of America (HCA), Health Net (HNT), Humana (HUM), Magellan Health (MGLN) and Anthem / Well Point (WLP). Over the two-day trading window, the Court’s decision drove down the price of a variety of health insurance companies while simultaneously increasing the value of one large hospital conglomerate (HCA) and a healthcare management business (MGLN). Interestingly, each of the stocks of the health insurance companies that ultimately trended downward experienced a significant short term uptick in the immediately aftermath of the Court’s decision. This is likely due to the widespread initial misreporting of the Court’s decision, which appeared to engender market confusion in the immediate aftermath of the Court’s ruling.14 However, unlike the Myriad case discussed earlier, the market quickly corrected itself in response to the subsequent accurate reporting of the Court’s decision. Collectively, among the stocks we evaluated in this study, the Obamacare decision was responsible for absolute changes in shareholder wealth in excess of 6.3 billion dollars.

Very cool.

In 2011, I noted that Ted Franks (who is now my attorney) made an investment decision based on his predicted outcome in Wal-Mart v. Dukes. He was so confident that the Supreme Court would reverse the 9th Circuit that he made a leveraged bet–of 10% of his net assets–that WMT (Wal-Mart’s symbol) will bounce. At the time, 76% of FantasySCOTUS members predicted a reversal. The great, and late Larry Ribstein suggested markets need greater sources of information to make these sorts of investments.

Unfortunately, Ted’s bet didn’t pan out. WSJ Law Blog reported:

No, unfortunately for the lawyer he was in court all morning, challenging the $3.4 billion settlement reached in 2009 in the high-profile Indian trust litigation, which claims the federal government mismanaged the revenue in American Indian trust funds. (Here’s an LB post on the settlement in that case.)

Frank told the Law Blog that by the time he got out of the Cobell settlement hearing, for a noon lunch break, he had missed the bump from the Dukes ruling.

“There were 90 people in the courtroom,” he said. “I couldn’t say, ‘can we stop the proceedings, because I need to engage in a stock sale.’”

Now, it seems Ted is not alone. Others are taking advantage of their SCOTUS predicting prowess.