One of the ongoing debates of the Obama Presidency has been the import of his frequent comments about the Supreme Court. It began in 2010 with his comments about Citizens United at the State of the Union, continued through 2012 with his comments about NFIB v. Sebelius, and has now continued to 2015 with King v. Burwell. One school of thought insists that this is no big deal at all, that the Justices are grownups, and won’t be influenced at all, so we shouldn’t worry about it. The other school of thought contends that President Obama’s criticisms of the Court are an attempt to influence the Justices. Randy Barnett and Larry Tribe describe different strains of this critique:

Randy Barnett, the Georgetown University professor who pursued the first case, told The Daily Telegraph in 2012 the remarks were a “gross mischaracterization of the relationship of the courts to Congress. … There really wasn’t anything in that statement that was accurate.”

And Laurence Tribe, Obama’s law professor at Harvard , was equally critical in 2012. “Presidents should generally refrain from commenting on pending cases during the process of judicial deliberation. Even if such comments won’t affect the justices a bit, they can contribute to an atmosphere of public cynicism that I know this president laments.”

I addressed these comments at some length in Unprecedented.

This week, the President offered more comments at a Press Conference and a speech to the Catholic Health Association (where he mentioned mammograms but not abortifacients). Washington Post Reporter Bob Barnes said “I was a little surprised President Obama weighed in again this week, saying the court probably should not have taken the case..” I wasn’t. Dana Milbank summarized in WaPo the President’s message in three words “You wouldn’t dare.”

He was speaking not to the hundreds of hospital administrators assembled for the Catholic Health Association’s conference but to five men not in the room: the conservative justices of the Supreme Court, who in the next 21 days will declare whether they are invalidating the most far-reaching legislation in at least a generation because of one vague clause tucked in its 2,000 pages.

Obama’s appeal to the justices, devotees of judicial modesty all: Do they really wish to cause the massive societal upheaval that would come from killing a law that is now a routine part of American life?

“Five years in, what we are talking about is no longer just a law. It’s no longer just a theory. It isn’t even just about the Affordable Care Act or Obamacare,” he said. “This is now part of the fabric of how we care for one another. This is health care in America.”

Michael Cannon, one of the architects of King v. Burwell, states the issue from the other side:

Today the president delivered a speech designed to cow the Supreme Court Justices into turning a blind eye to the law.

How do we put President Obama’s comments into context? Well, one way is to see how previous Presidents discussed the Supreme Court. The National Constitution Center Blog identifies “other Presidents [that] have publicly questioned court decisions.” Who are the examples NCC came up with? FDR, TR, Jackson, and Lincoln.

Franklin Roosevelt, in particular, engaged in Supreme Court name calling in the early parts of his four-term presidency. At one point, Roosevelt told reporters the Court’s decision were remnants of the “horse and buggy definition of interstate commerce.”

Roosevelt’s fifth cousin, Theodore, also lambasted the Supreme Court in his 1908 State of the Union address. “Judges of this stamp do lasting harm by their decisions because they convince poor men in need of protection that the courts of the land are profoundly ignorant of and out of sympathy with their needs,” he said.

Andrew Jackson and Abraham Lincoln were also sharply critical of the Supreme Court at times, and Thomas Jefferson’s battles with the early Court left a vivid impression on the third President.

“This member of the Government was at first considered as the most harmless and helpless of all its organs. But it has proved that the power of declaring what the law is, ad libitum, by sapping and mining slyly and without alarm the foundations of the Constitution, can do what open force would not dare to attempt,” he remarked in 1825.

I wrote a section on this topic for Unprecedented, looking at statements made leading up to and in the aftermath of Bush v. Gore, but ultimately cut it (I cut nearly 30,000 words in total!). Consider former House Minority Leader Richard Gephardt:

On the Sunday before Bush v. Gore was decided, House Minority Leader Richard Gephardt (D-Mo.) told ABC’s This Week that “I just don’t think we get anywhere by criticizing courts as being partisan, questioning their motives and their integrity.” Gephardt acknowledged the finality of the Supreme Court’s ruling, and said “I believe [Gore] will” concede if the court rules for Bush.

Here is Vice President Gore’s concession speech:

“Now the U.S. Supreme Court has spoken. Let there be no doubt, while I strongly disagree with the court’s decision, I accept it. I accept the finality of this outcome which will be ratified next Monday in the Electoral College. And tonight, for the sake of our unity of the people and the strength of our democracy, I offer my concession.”

Relatedly, here is President Bush’s statement following the Court’s decision in Boumediene:

“We’ll abide by the court’s decision. That doesn’t mean I have to agree with it. It’s a deeply divided court, and I strongly agree with those who dissented.”

I hope President Obama offers similarly magnanimous remarks if the Court rules against him in King v. Burwell.

Update: Russell Berman at the Atlantic asks if the President’s remarks was an attempt to “jawbone the justices at the 11th hour.”

It was that final phrase—“woven into the fabric of America”—that seemed most directed at lawmakers in the Capitol and the justices on the Supreme Court. For Obama, the fight to preserve the healthcare in the face of a serious legal challenge carries a sense of deja vu. It was three years ago this month that Roberts alone, straddling the ideological poles on the court, decided to save Obamacare by declaring its requirement that Americans purchase insurance a constitutional exercise of Congress’s taxing power. The difference this time around, Obama not-so-subtly argued, is that the law is no longer “myths or rumors.” It is a reality, and so too would be the consequences of unraveling it. “This is now part of the fabric of how we care for one another,” Obama said. “This is healthcare in America.”

Charles Fried (who hasn’t made any promises to eat his hat over this case) weighs in:

Yet there’s less evidence that even the most persuasive use of the bully pulpit can sway the justices. “Would it help or hurt? I can’t imagine it’ll make any difference, and I can’t imagine he thinks it’ll make any difference,” said Charles Fried, the Harvard law professor who argued cases before the court as Ronald Reagan’s solicitor general. (Fried has weighed in on the Obama administration’s side in King v. Burwell.) … “I would think the die is cast,” Fried said.

He closes with a reference to how the “fabric” will “unravel.”

The argument you’ll hear is the same one he made on Tuesday: The Affordable Care Act is now the reality of healthcare in America—“woven into the fabric”—and the painful disruptions and the parade of horribles that Republicans predicted five years ago will now only come to pass if they allow it to unravel. Of course, Obama could easily have waited a few weeks to deliver the speech, if he needed to give it at all. But Obama apparently wanted to begin mounting his case now—and, perhaps, sway any justice who might be having last-minute doubts.

This book writes itself.

Update: The WSJ Editorial Board weighs in:

That last bit of political bravado is belied by the previous display of legal frustration. A seasoned observer like Mr. Obama must know that it does him no good to lacerate the Justices in public if he’s trying to influence them to come his way. His best strategy would be silence. Our suspicions were raised even more on Tuesday when Mr. Obama gave a full-throated defense of his signature health law that assailed opponents and gave the impression he’s not going to alter a single letter no matter what the Court does.

Could it be that legal sources are telling Mr. Obama that he’s about to lose, so he is now beginning to prepare the public for an all-out assault on the Court and Republicans?

Update: Jess Bravin finds three Presidents who made comments about pending cases.

Presidential commentary on pending cases has proved remarkably ineffective.

In a June 5, 1976, interview, President Gerald Ford told CBS News that parents should be able to send their children to whites-only private schools. “Individuals have a right where they are willing to make the choice themselves and there are no taxpayer funds involved,” Mr. Ford said.

The Supreme Court disagreed, ruling on June 25 that such discrimination was a “classic violation” of the Civil Rights Act of 1866.

In 1989 and 1992, while abortion cases were pending, President George H.W. Bushexpressed hope the court would overrule Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision recognizing abortion rights.

The court has yet to do so.

In January 2003, President George W. Bush called on the court to rule against separate affirmative-action programs at the University of Michigan’s undergraduate college and law school. “The Michigan policies amount to a quota system that unfairly rewards or penalizes prospective students, based solely on their race,” he said.

The United States filed briefs in Grutter and Casey.

But a study by Paul Collins, author of a study on Presidential Rhetoric and the Supreme Court, suggests that these comments go far beyond the normal:

On most occasions, presidents have only briefly noted the existence of a Supreme Court case. Mr. Obama, who taught law at the University of Chicago, has tended to go further, Mr. Collins and his co-author, University of North Texas professor Matthew Eshbaugh-Soha, found.

“Most of the statements that presidents make tend to be a sentence or two or three sentences,” Mr. Collins said, adding that Mr. Obama on Monday “went on for 3½ minutes by my count, and he didn’t mince words.”

While there have been about 50 instances between 1953 and 2012 when presidents have mentioned pending cases, Mr. Collins said most presidential commentary has concerned decisions after they are announced.

There are good reasons for that, he said.

When presidents discuss pending litigation, “they are violating this very strong norm of judicial independence, that presidents and other political actors shouldn’t get involved” when the court is deliberating, Mr. Collins said. “It’s not done.”

…

“One of the suspicions that Matt and I have is that they might be doing it for cases they perceive are at risk, so it could be that Obama is getting nervous,” Mr. Collins said. “One way this could benefit him if his side loses is that it at least makes the public understand that there’s another perspective to interpret the statute.”

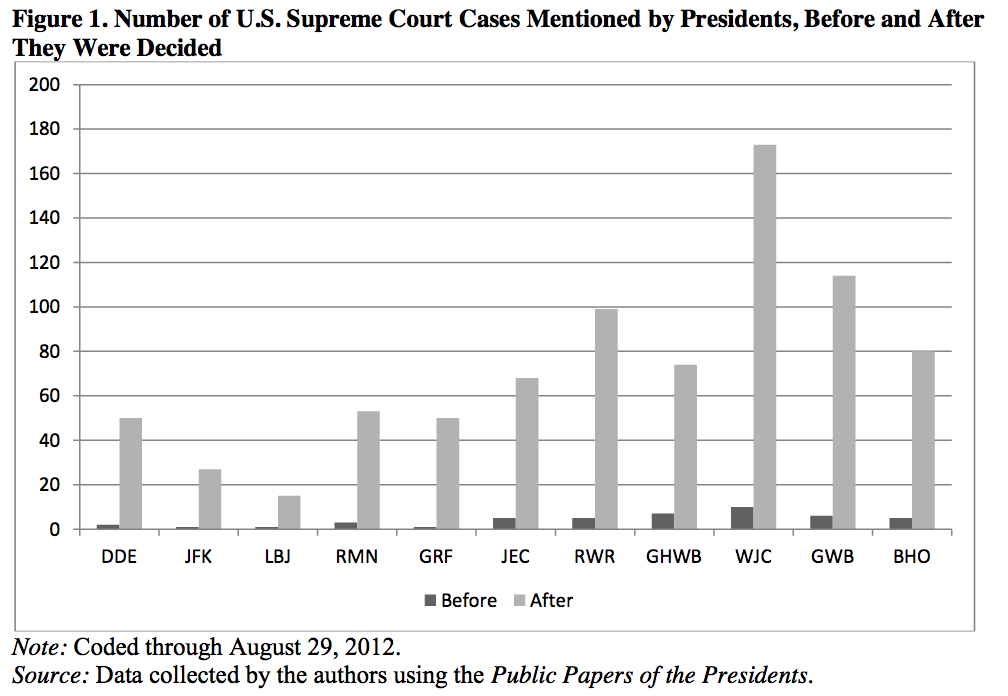

And some highlights from the study:

Thus, our finding suggests that presidents generally refrain from discussing pending cases in their public rhetoric to avoid violating the norm of decisional independence, lending support for research that shows how norms shape the behavior of political actors (e.g., March and Olson 2004; Peters 2012).

First, presidents seldom discuss pending Supreme Court cases, choosing instead to speak about cases after they have been adjudicated. This finding is important because it reveals that presidents do not actively seek to influence judicial decision making through their public commentary. As we argue, this is likely a partial function of presidential deference to the norm of decisional independence, coupled with the ability of the Solicitor General to provide the Court with information regarding the president’s preferred policies in legal briefs and during oral arguments.

…

As Figure 1 illustrates, nearly all of the president’s comments concerning Supreme Court cases occur after the Court has ruled. On only 47 occasions—or 5 percent of the time—has the president mentioned a Supreme Court case prior to a decision. And, although it has become somewhat more common since the Carter Administration for presidents to address cases prior to a ruling, no president has made more than 10 such appeals. Thus, presidents are not speaking about Supreme Court cases in a manner consistent with how scholars envision that presidents go public on legislation before Congress—to put public pressure on legislators to support the president’s position (Kernell 1997). Rather, they tend to speak about cases for reasons other than attempting to influence the Court.

Fourth, presidents who were trained as lawyers speak (but do not write) more frequently about historic Supreme Court cases than non-lawyers. More precisely, lawyers mention historic cases in about 69 percent more speeches than their non-lawyer counterparts. This suggests that presidents who were lawyers may be more comfortable than non-lawyers in speaking extemporaneously about Supreme Court decisions. Presumably, this is because their background training makes them more familiar than non-lawyers with the substance of the Court’s historic decisions and therefore more willing to discuss those decisions in public.