I am pleased to announce that my article, “The Constitutionality of DAPA Part I: Congressional Acquiescence to Deferred Action” will be published in the Georgetown Law Journal Online. You can download a draft on SSRN.

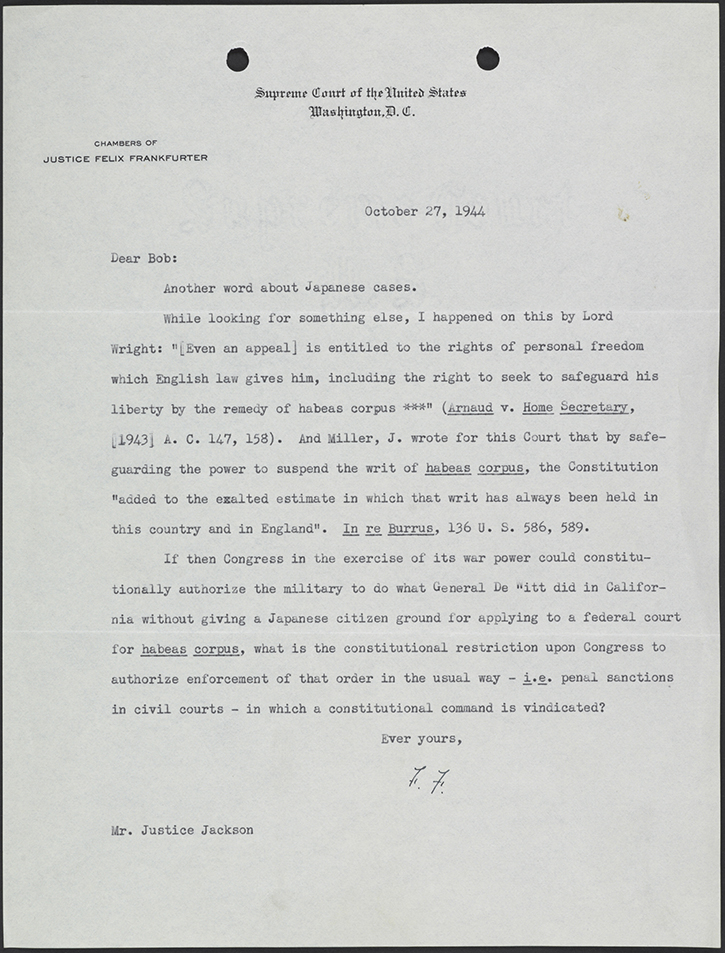

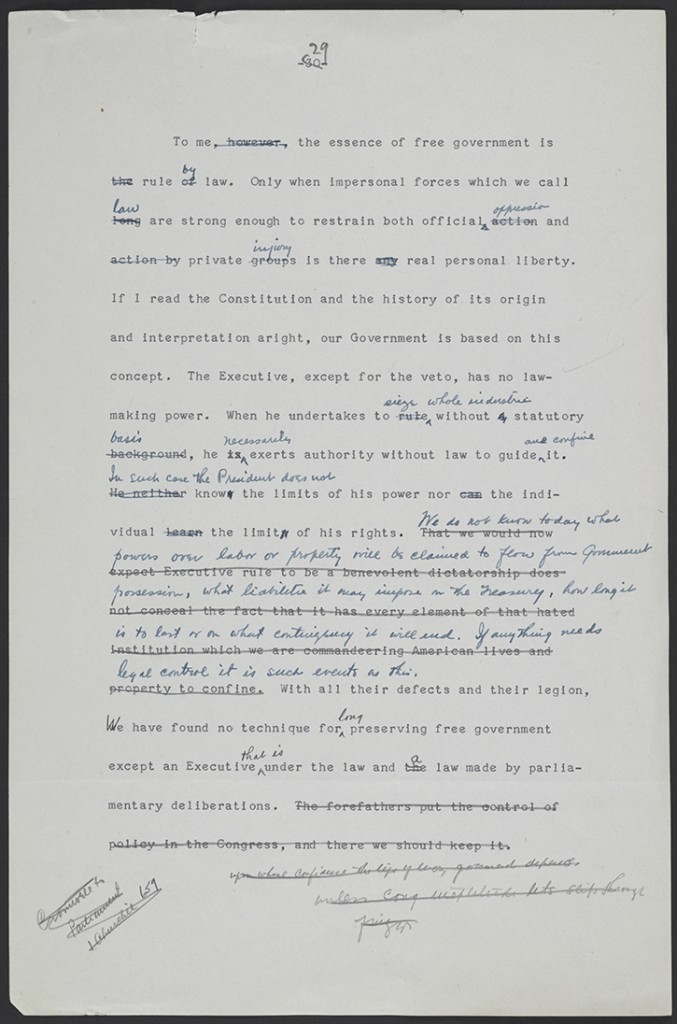

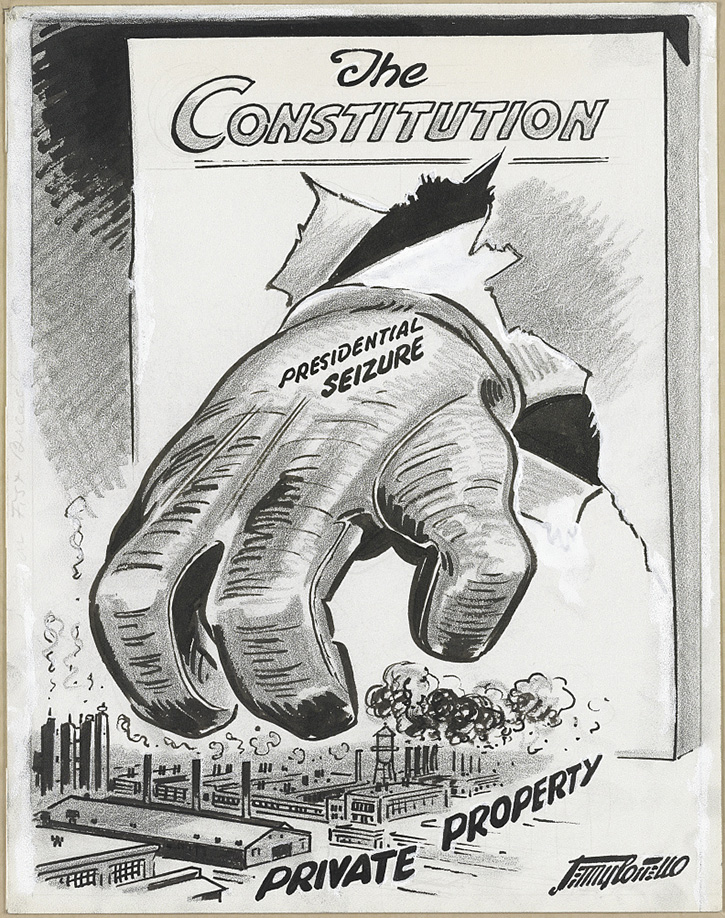

My initial reaction on November 19 when I read the OLC Opinion justifying DAPA was one of unease. On the one hand, the framework the opinion set out seemed to make sense: “an agency’s enforcement decisions should be consonant with, rather than contrary to, the congressional policy underlying the statutes the agency is charged with administering.” Putting aside all the nuances of Chevron or Heckler v. Cheney, this is in essence how Justice Jackson framed the question of executive power in Youngstown. If the President is acting in accordance with Congress’s express or implied will, then the President is almost certainly acting lawfully. In order to determine whether Congress has impliedly or tacitly gave its blessing to the President’s action, the memo looked to whether Congress acquiesced to previous forms of deferred action. So far, so good. My initial inclination was that Congress had given such a blessing to the President with respect to deferred action.

I even wrote an Op-Ed in the L.A. Times the following day (the editor gave me less than 14 hours to write it) faulting Congress for giving too much discretion to the President on immigration.

Over the last 60 years, Congress has given the president virtually unlimited authority over immigration enforcement, and then it has stood back and acquiesced as one chief executive after another continued exempting groups from the naturalization laws, with no repercussions.

I had heard this line so often, that I assumed it had to be true. Even panelists at the Federalist Society convention seemed to acquiesce to this accepted wisdom. The only program, is that it’s not true. Not even close.

What initially got my spidey-senses tingling was when I dug into the oft-repeated story that President George H.W. Bush deferred the deportations of 1.5 million. After some research, I found that the situations were entirely dissimilar, as Bush intended it as a temporary stopgap measure–Congress was about to imminently pass comprehensive legislation. The deferred action served to bridge aliens who had a visa waiting on the side. The 1.5 million number is also inaccurate–the real number is closer to 50,000.

While I fully expected OLC to play fast and loose with the law, I at least expected them to accurately restate the facts and history with respect to immigration policy. The George H.W. Bush story gave me serious pause, and forced me to start double-checking all of the factual predicates made in the OLC opinion.

Thanks to the help of several colleagues who are experts in immigration law, I began to learn that OLC makes several key errors. To (grossly) summarize, Congress has instituted a complex scheme for the conferral of benefits on aliens, including the unlawfully present parents of U.S. citizen and lawful permanent resident children. Although this scheme indicates Congressional intent to favor family unification, it represents a narrow policy in furtherance of this goal. The family unification scheme is limited in terms of (1) who can obtain relief, (2) what must be demonstrated in order to establish statutory eligibility, and (3) the potentially lengthy wait one must endure before a visa or other relief may be available. DAPA undercuts all three goals. Specifically, it effectively negates Congress’s considered judgment to disallow relief to the parents of minor citizen children, while extending relief to the parents of lawful permanent residents, a class that has never been entitled to preferential treatment under the immigration laws.

The opinion overstates the degree to which the Immigration and Nationality Act (“INA”) is concerned with family unification, misapprehends the extraordinarily narrow scope of relief provided to the parents of U.S. citizen and lawful permanent resident children under existing law, and misstates the limited scope of prior Congressional acquiescence to deferred action programs. These flaws undercut the opinion’s key conclusion that DHS’s deferred action programs are consistent with Congressional policy, and thus also place into question the ultimate judgment that these initiatives are permissible exercises of enforcement discretion.

Specifically, OLC noted five prior exercises of deferred action “to certain classes of aliens” supported by Congress, and opined that DAPA is consistent with the scope and intent of these prior programs: deferred action for (1) VAWA self-petitioners, (2) T and U visa applicants, (3) foreign students affected by Hurricane Katrina, (4) widows and widowers of U.S. Citizens, and (5) Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (“DACA”). This is simply not the case. The first four incidences of deferred action were all sanctioned in one way or another by Congress. In these cases, one of two conditions exists: (1) the alien had an existing lawful presence, or (2) the alien has the immediate prospect of lawful residence or presence. For each, deferred action acted as a temporary bridge from one status to another, where benefits were construed as immediately arising post-deferred action. These currents bring the deferred action within the ambit of Congressional policy embodied inside the INA. Further, all of these deferred actions were several orders of magnitude smaller than DAPA, and were expressly or impliedly approved of by Congress. However, none of these principles holds true to the fifth incidence, DACA, or its close-cousin DAPA.

In short, DAPA represents a fundamental rewrite of the immigration laws that is inconsistent with the Congressional policy currently embodied in the INA. As OLC explained, “an agency’s enforcement decisions should be consonant with, rather than contrary to, the congressional policy underlying the statutes the agency is charged with administering.” DAPA is contrary to, rather than consonant with the congressional policies underlying the INA. It is in palpable tension with the statute and the intent Congress evidenced in enacting the relevant provisions. To the extent that DAPA’s constitutionality rests on congressional acquiescence, OLC has failed to carry this burden.

These findings spurred my article, “The Constitutionality of DAPA Part I: Congressional Acquiescence to Deferred Action.” (If you wondered why I was so quiet on this blog in December–half as many posts as usual–this is why).

This article’s scope is narrow and means to address only the question of whether or to what extent deferred action for the parents of U.S. citizen and lawful permanent resident children is consistent with Congressional policy as currently embodied by the INA. The second part of this series will consider whether the President complied with the “Take Care” clause. See Josh Blackman, The Constitutionality of DAPA Part II: Faithfully Executing The Law, 19 Tex. R. of Law & Pol. __ (2015 Forthcoming).

I will announce another important development on DAPA tomorrow.