During my trip to Washington, D.C. last week, I visited the excellent Magna Carta exhibit at the Library of Congress (principally sponsored by the Federalist Society). The Lincoln Magna Carta leaves America on January 19, and will return to England where it previously stayed for 800 years. The LOC site posts some of the highlights.

What I loved about the exhibit was how it tied a thread from Magna Carta to the present day by focusing on how the rule of law has evolved.

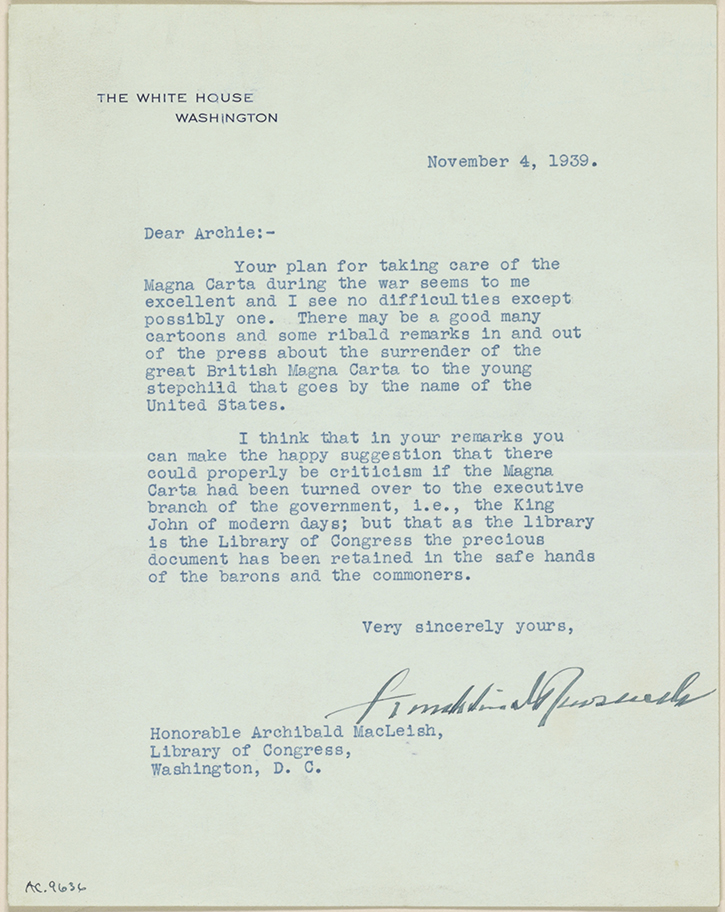

First, during World War II, the Brits sent Magna Carta to the Library of Congress for safekeeping. FDR quipped that the Magna Carta will be safe not with the “executive branch of the government, i.e., the King John of modern days; but that as the library is the Library of Congress the precious document has been retained in the safe hands of the barons and the commoners.”

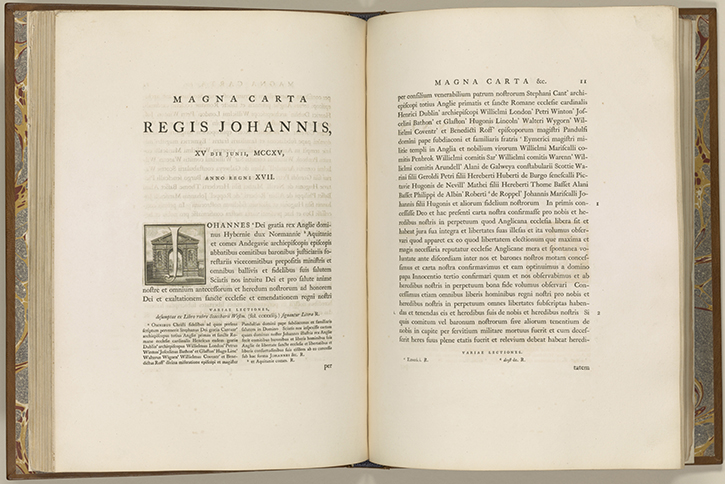

They had a lot of fascinating primary sources discussing Magna Carta. Here is a First Edition of Blackstone’s Commentaries:

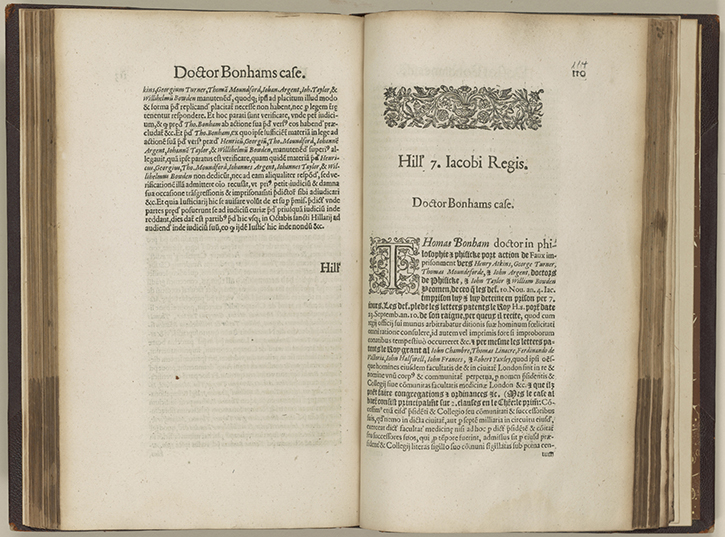

Here is an original copy of Doctor Bonham’s Case by Lord Coke.

Unlike the National Archives–whose exhibit on the Constitution was woefully inadequate and would not even let me read the Constitution–the Library of Congress did a fantastic job at connecting Magna Carta to the U.S. Supreme Court.

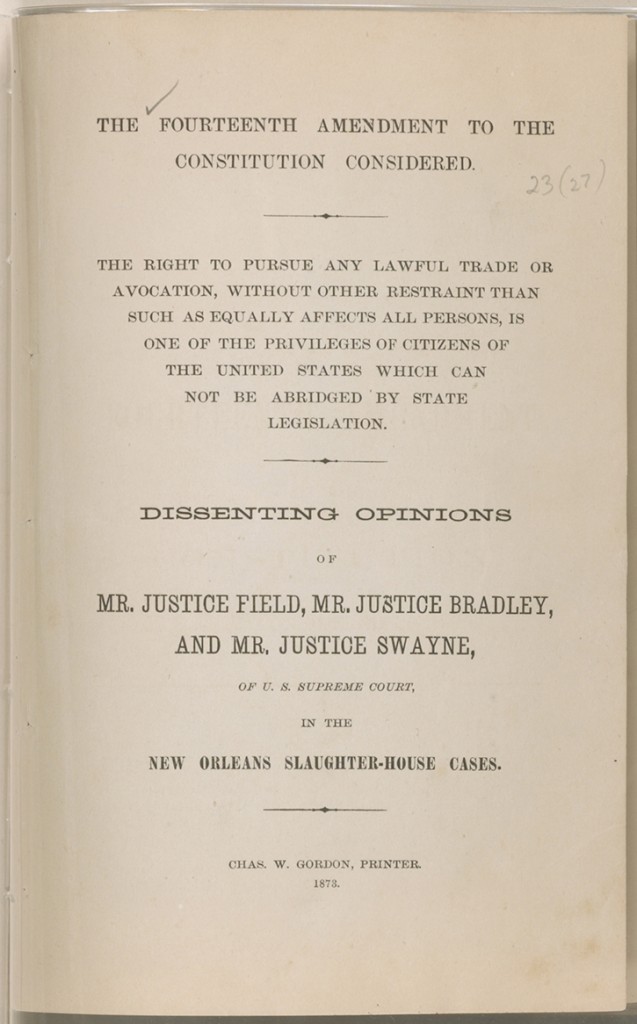

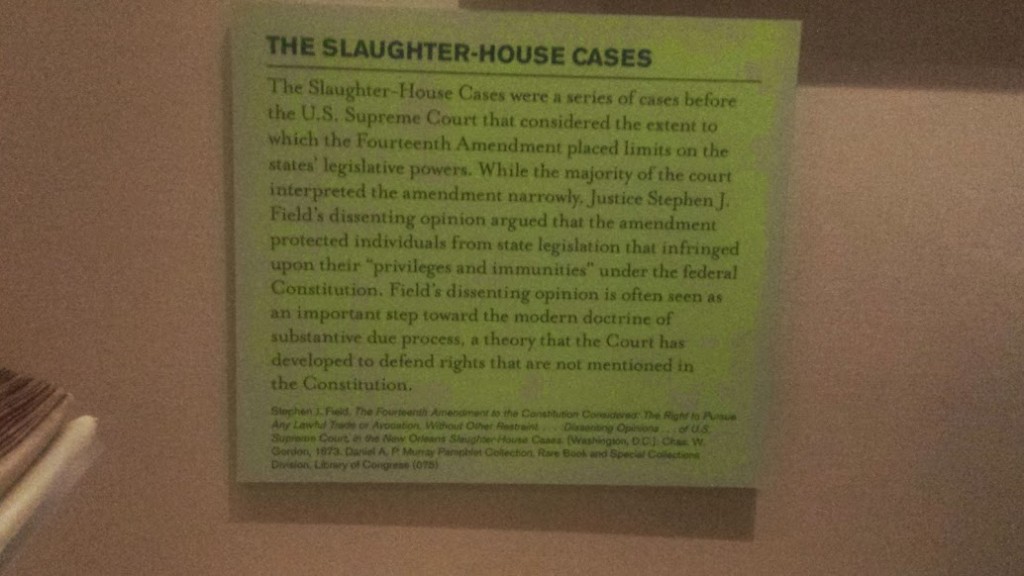

They even had an exhibit on Magna Carta, the Privileges or Immunities Clause, and the Slaughter-House Cases.

Although tragically, in the description, they wrote the “Privileges and Immunities Clause.”

I tweeted the Library of Congress, and actually got response!

@JoshMBlackman@librarycongress Thanks for tweeting your visit to the exhibit and pointing that out.

— LawLibraryofCongress (@LawLibCongress) January 2, 2015

The exhibit also had great references to key Supreme Court decisions implicating the liberties protected by Magna Carta, including Korematsu and Youngstown.

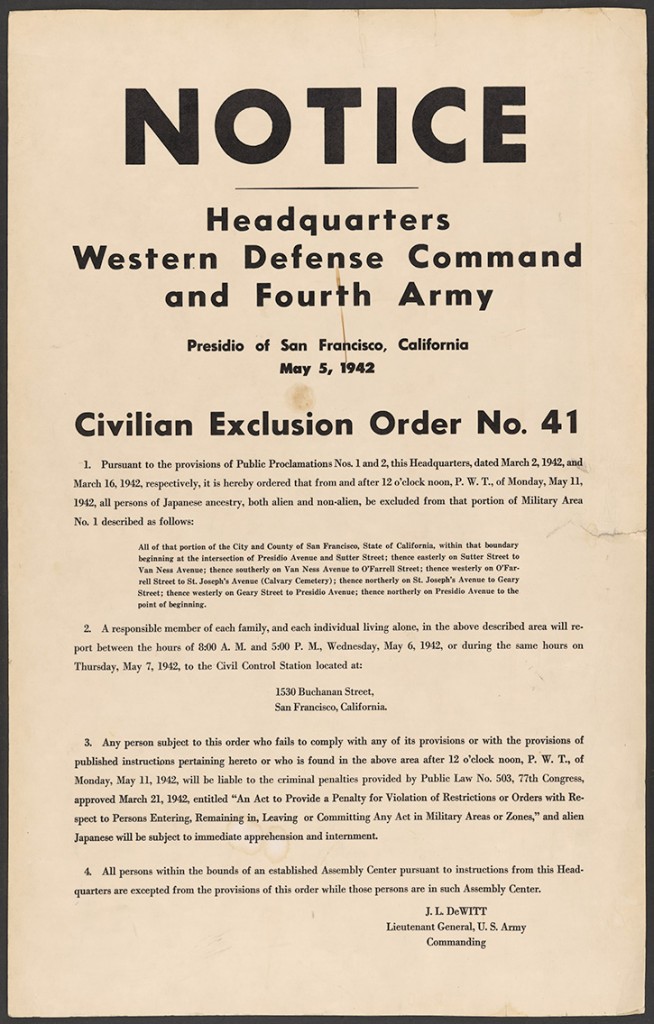

This is Civilian Exclusion Order No. 41, which triggered Korematsu.

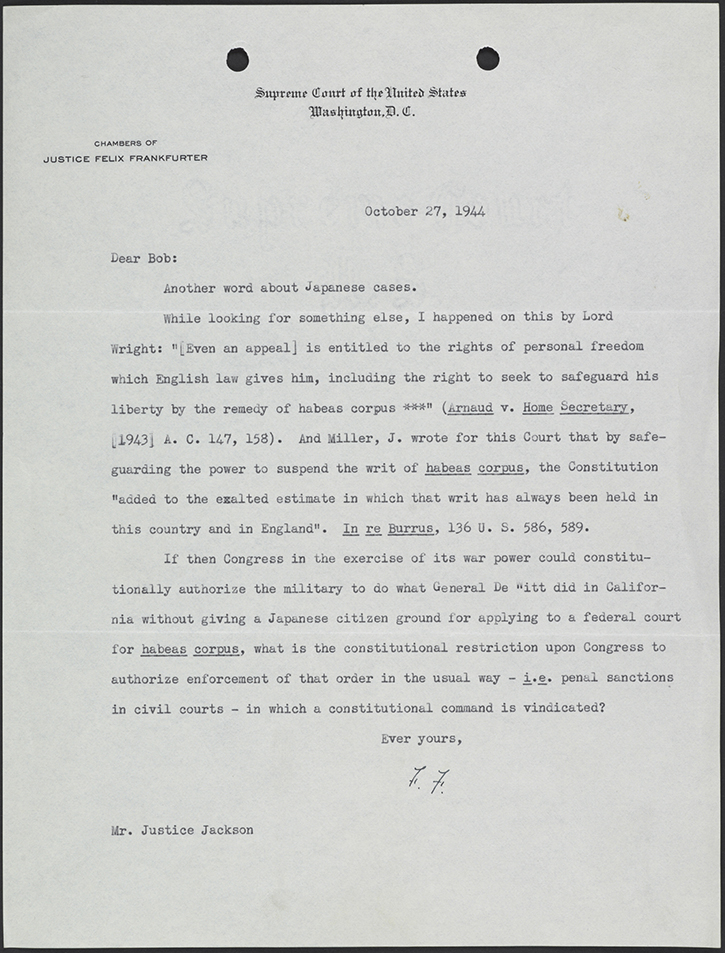

Here is a letter from Justice Frankfurter to Justice Jackson (“Bob”) providing a citation to Lord Wright for Korematsu.

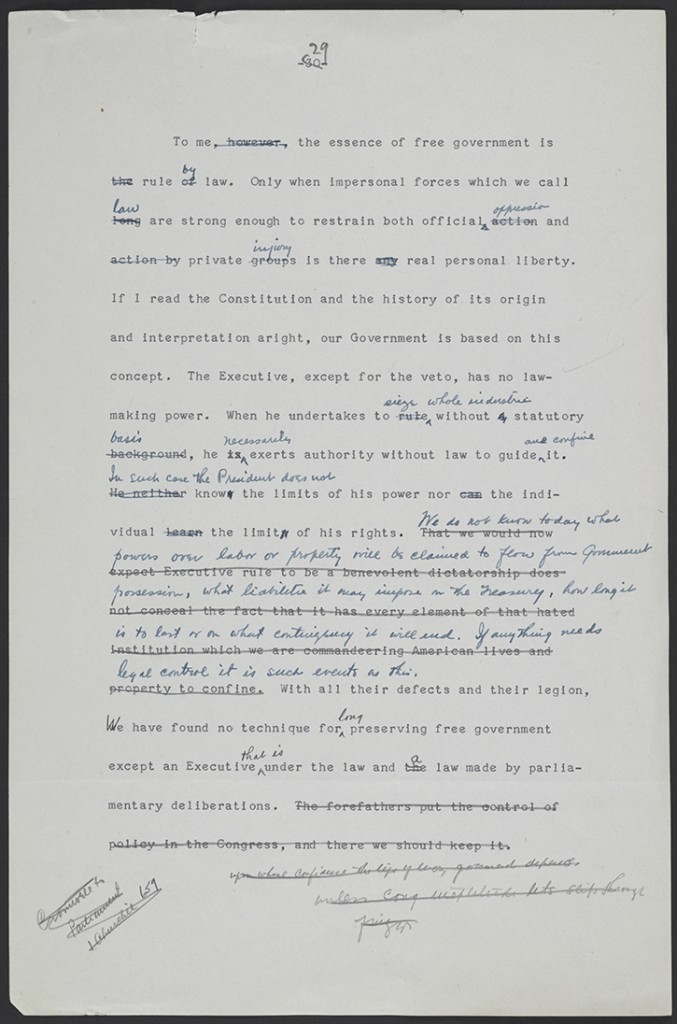

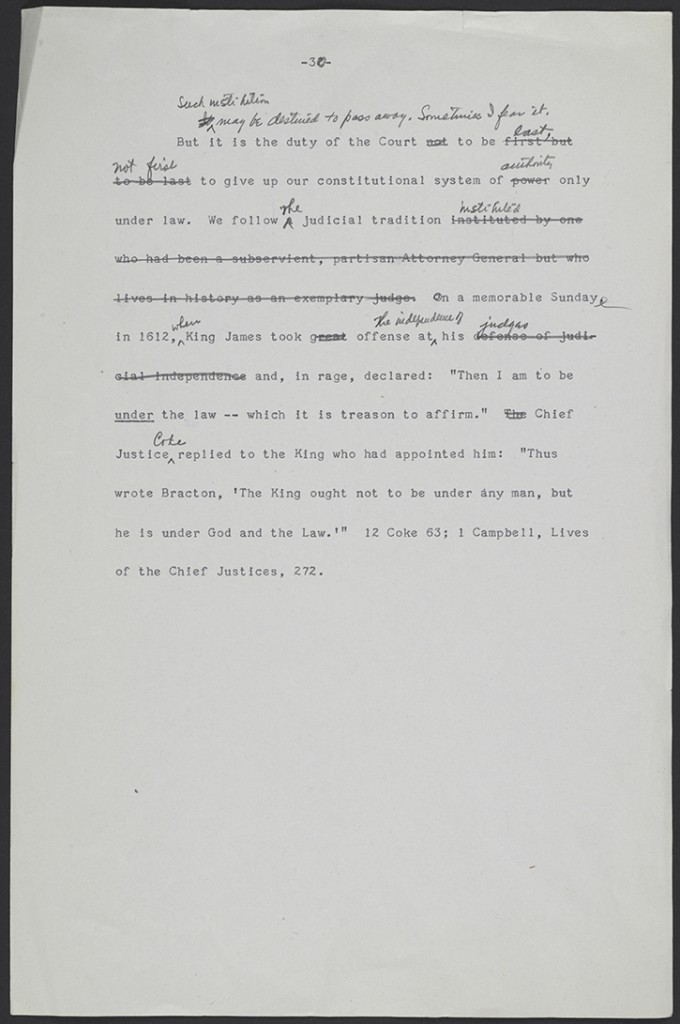

With respect to Youngstown, here is Justice Jackson’s draft opinion. This must be a fairly early draft, as there are quite a number of changes made before his final concurring opinion.

On this page, consider the original:

But it is the duty of the Court not to be the first but to be last to give up our constitutional system of power only under law.

Now consider the edited version:

Such institutions may be destined to pass away. Sometimes I fear it. But it is the duty of the Court to be last, not first to give up our constitutional system of authority only under law.

Now consider the final reported version.

Such institutions may be destined to pass away. But it is the duty of the Court to be last, not first, to give them up.

He removed the “Sometimes I fear it” line. Everything that came afterwards was put into the famous footnote 27.

We follow the judicial tradition instituted on a memorable Sunday in 1612, when King James took offense at the independence of his judges and, in rage, declared: “Then I am to be under the law – which it is treason to affirm.” Chief Justice Coke replied to his King: “Thus wrote Bracton, `The King ought not to be under any man, but he is under God and the Law.'” 12 Coke 65 (as to its verity, 18 Eng. Hist. Rev. 664-675); 1 Campbell, Lives of the Chief Justices (1849), 272.

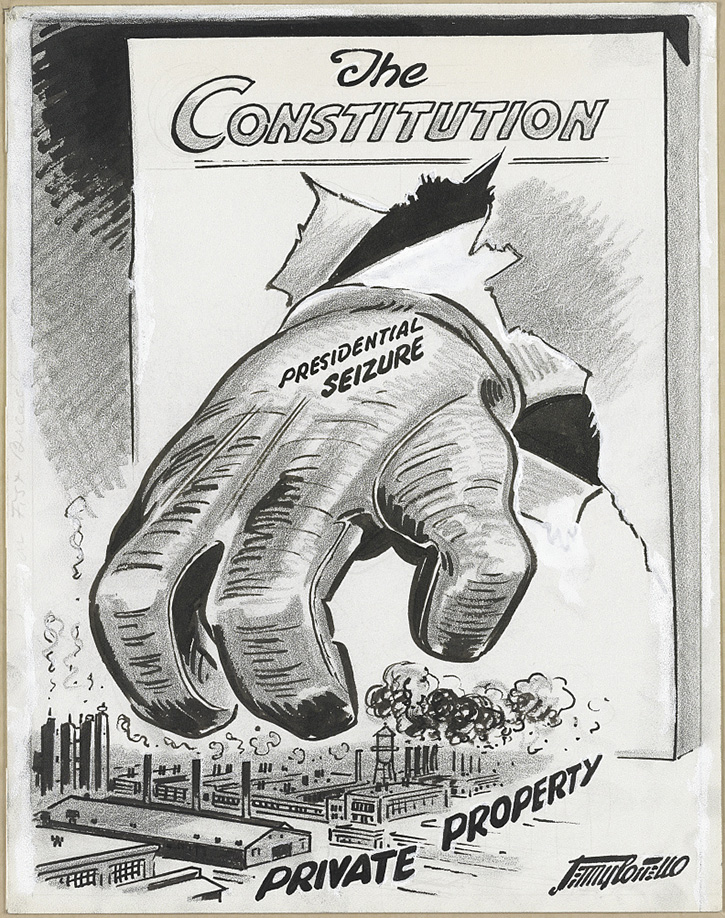

And here is a fitting political cartoon about Youngstown.

And here is a fitting political cartoon about Youngstown.

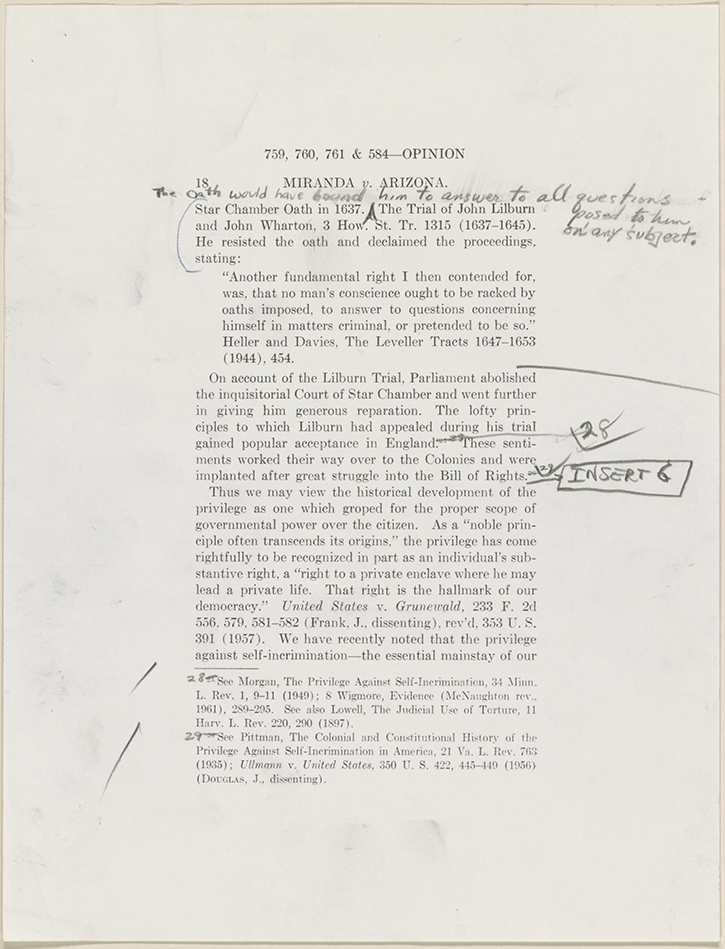

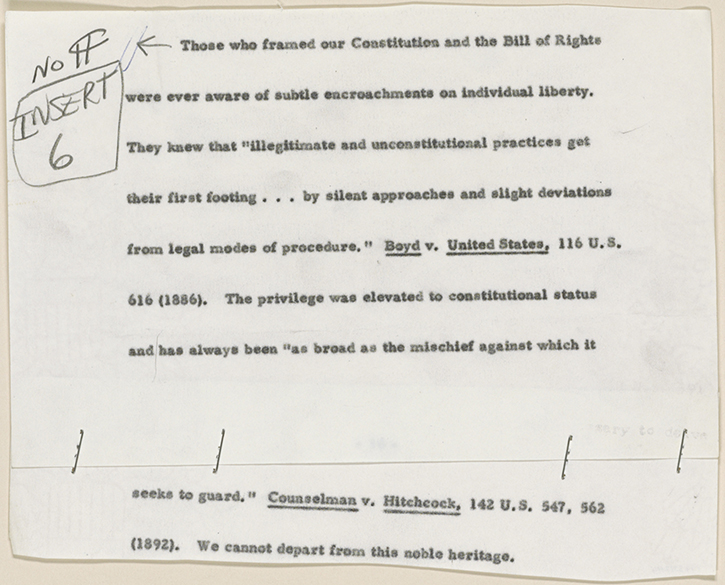

And here are Chief Justice Warren’s notes on Miranda:

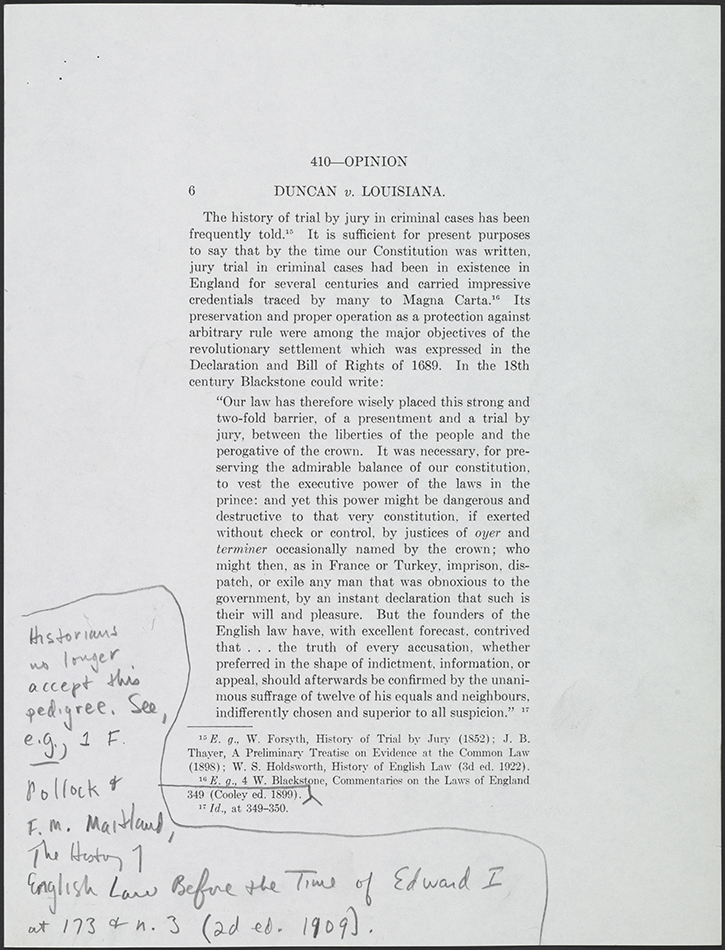

And here is Justice White’s decision in Duncan v. Louisiana: