In my article, “The Constitutionality of DAPA Part II: Faithfully Executing the Law,” I provide an overview of the text and history of the Take Care clause, with an eye towards understanding what “faithfully” means. Specifically, I recount the evolution of the clause during the Constitutional Convention, with changes made to accentuate the duty of good faith. Here is an excerpt of the paper, with footnotes omitted (though I cite passim the works of Zachary Price, Robert Delahunty and John Yoo, Saikrishna Prakash, Randy Barnett, and others).

—

The Take Care clause draws from a rich pedigree of colonial-era Constitutions limiting state executives from suspending the law. The post-revolutionary Constitutions of New York,[1] Pennsylvania,[2] and Vermont[3] employed similar standards to define the role of the executive, all requiring some variant of “faithfully executed.” By 1787, six states “had constitutional clauses restricting the power to suspend or dispense with laws to the legislature”[4]—Delaware,[5] Maryland,[6] Massachusetts,[7] North Carolina,[8] New Hampshire,[9] and Virginia.[10]

During the Constitutional Convention, the President’s duty to execute the laws went through several evolutions. These changes highlight the importance of the duty of faithfulness to the framers. An early version of the Take Care clause appeared in the Virginia Plan on May 29, 1787. It vested the “National Executive” with the “general authority to execute the National laws.”[11] On June 1, James Madison “moved,” and “seconded by” James Wilson, the Convention adopted a version of the clause: the Executive was “with power to carry into execution the national laws.”[12] At this point, there were no qualifications for faithfulness. A proposal to give the President the power “to carry into execution the nationl. [sic] Laws” was agreed to unanimously on July 17.[13]

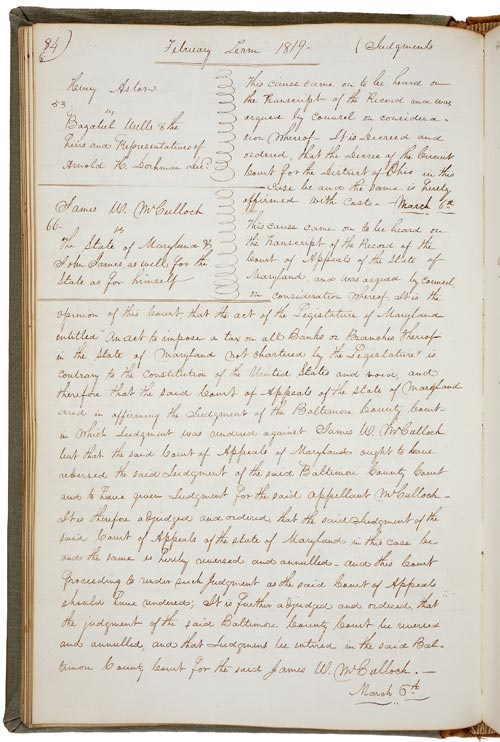

On July 26, this provision was sent to the Committee of Detail.[14] The Committee of Detail considered two different formulations. First, “[h]e shall take Care to the best of his Ability.”[15] Second, John Rutledge suggested an alternate: “[i]t shall be his duty to provide for the due & faithful exec[ution] of the Laws.”[16] The final version, reported out by the Committee on August 6, hewed closer to Rutledge’s proposal: “he shall take care that the laws of the United States be duly and faithfully executed.”[17] Elliot’s Debates recorded the same draft.[18] The Committee of Detail rejected a provision that would have been linked to the “best of” the President’s “ability,” which was ultimately adopted in the oath of office.[19] Rather, the Committee focused on “due” and “faithful” execution.

The draft that was “referred to the Committee of Style and Arrangement”[20] on September 8 still included the phrase “duly.”[21] However, the final report of the Committee of Style dated September 12, phrased the “take care” clause in its final form, dropping the “duly.” It read, “shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed.”[22] There is no recorded account of why “duly” was dropped, and the focus was placed solely on “faithfully.”

The progression over the summer of 1787 speaks to the designs of the framers. The initial draft from the Virginia Plan imposed no qualifications—the President was simply to “execute the National laws.”[23] Full stop. The Committee of Detail considered proposals that would restrict the duty to either (a) “the best of his Ability” or (b) “the due & faithful exec[ution] of the Laws.”[24] The Committee chose the latter. Finally, the Committee of Style—staffed by Madison and Hamilton, 2/3 of Publius—narrowed the duty to focus only on “faithfully.” This account is confirmed by Alexander Hamilton’s Plan, which though “not formally before the Convention in any way,” was read on June 18 and proved to be influential.[25] His plan eliminated the phrase “duly” and only focused on “faithfully”—“He shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed.”[26] Hamilton echoed this phrasing in Federalist No. 77, where he wrote about the President “faithfully executing the laws.”[27]

What is the difference between “duly” and “faithfully”? Johnson’s Dictionary defines “due” as “that which any one has a right to demand in consequence of a compact.”[28] The omission of “duly” and focus on “faithfully” suggests a shift away from legal duties to one of faithfulness on the part of the President.

This construction was confirmed by the Oath Clause of Article II: “I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the Office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my Ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.” Again, the framers required the President to swear that he will “faithfully execute” those duties charged to him. However, unlike the “Take Care” clause, which is imposed without qualification, the Oath only binds the President “to the best of [his] Ability.” In this sense, the imperative to “preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States,” though it must be “faithfully executed,” exists to a lesser degree—to the “best of my Ability.”[29] In contrast, the New York Constitution of 1777 provided that the governor is “to take care that the laws are faithfully executed to the best of his ability.”[30] Further, the “Take Care” clause did not include language such as “shall think proper,” as this optional language is used in the adjournment clause.[31] The duty looks to one of faith. This understanding was further confirmed in the ratification conventions.

At the Pennsylvania Ratification Convention, James Wilson—himself a member of the Constitutional Convention and a future Supreme Court Justice—explained the relationship between the President and Congress: “It is not meant here that the laws shall be a dead letter; it is meant, that they shall be carefully and duly considered, before they are enacted; and that then they shall be honestly and faithfully executed.”[32] Wilson equates the duty of “faithfulness” with that of “honesty.”[33] Ten days later, Wilson stressed that the “Take Care” clause was “another power of no small magnitude entrusted to this officer,” the President. [34]

During the North Carolina Ratification Convention, delegate Archibald Maclaine stressed the importance of the “Take Care” clause: “One of the best provisions contained in it is, that he shall commission all officers of the United States, and shall take care that the laws be faithfully executed. If the takes care to see the laws faithfully executed, it will be more than is done in any government on the continent, for I will venture to say that our government, and those of the other states, are, with respect to the execution of the laws, in many respects, mere cyphers.”[35]

The history of the Take Care clause reveals a focus execution based on faith and honesty. As Prakash explained, “If the officer performed his duties honestly, adequately, and within the boundaries of his statutory discretion, the presidential inquiry would end, for the President would have taken care that the laws were faithfully executed.”[36]

Dr. Samuel Johnson’s 1755 A General Dictionary of the English Language, defines “faithfully” as imposing a very precise standard: acting “[w]ith strict adherence to duty and allegiance,” “[w]ithout failure of performance; honestly; exactly,” and “[h]onestly; without fraud, trick or ambiguity.”[37] Noah Webster’s influential 1828 defines faithfully as “in a faithful manner; with good faith.”[38] The second definition imposes an even higher standard: “with strict adherence to allegiance and duty.” Webster even offers as an example with reference to the Constitution, “the treaty or contract was faithfully executed.” With this selection of “faithful,” the framers seem to have adopted a standard stretching back to the times of Herodotus[39] to Roman law[40] to Canon law[41], and was well known in the 17th[42] and 18th[43] century English common law of contracts[44]—one of “good faith.”[45] As Professor Price observes, “the term ‘faithfully,’ particularly in eighteenth-century usage, seems principally to suggest that the President must ensure execution of existing laws in good faith.”[46]

Delahunty and Yoo conclude that the Take Care clause is “naturally read as an instruction or command to the President to put the laws into effect, or at least to see that they are put into effect, ‘without failure’ and ‘exactly.’”[47] However, this duty is not so mechanical. As Price counters, “the very separation of legislative and executive functions implies that enforcing the laws may be a matter of judgment, a task of applying general laws appropriately—‘faithfully’—in particular factual circumstances.”[48] The good faith standard, as developed in the common law of contract, provides a framework to understand for the scope of this discretion.

Steven Burton’s canonical work on the common law duty to perform in good faith is consistent with how the text and history of the Take Care clause.[49] Burton sketches two views of failing to comply with a contract. First, a party may deviate from the terms of the contract, resulting in the “deprivation” of “anticipated benefits” based on a “legitimate” or “good faith” reason. Here, there is no breach of contract, even though the contract was not strictly complied with. Second, however, “[t]he same act will be a breach of the contract if undertaken for an illegitimate (or bad faith) reason.” How should we distinguish between the former (lawful) and the latter (unlawful)? It is not enough to focus on the contractual duties owed to the promisee, and what “benefits [are] due” to him. Rather, to determine “good faith,” an inquiry must be made into the motivations of the promisor’s actions.

Burton explains, “Good faith performance, in turn, occurs when a party’s discretion is exercised for any purpose within the reasonable contemplation of the parties at the time of formation—to capture opportunities that were preserved upon entering the contract.” To put this in constitutional terms, we would ask whether the President is acting within the realm of possible discretion contemplated when Congress enacted a statute. If the answer is yes, the deviation from the law is in good faith, and is permissible. However, if the departure from the law is “used to recapture opportunities forgone upon contracting,” the action is not in good faith. As Randy Barnett explains, “According to Burton, when a contract allows one party some discretion in its performance, it is bad faith for that party to use that discretion to get out of the commitment to which he consented.”[50] To place this dynamic into constitutional terms, when the President relies on a claim of authority Congress withheld, as a means to bypass that statute, the action is in bad faith, and unlawful.

Under this theory, “[w]hat matters is the purpose or motive for the exercise of discretion.”[51] Good faith deviations that “honor the spirit” of the law or rely on “scarcity of enforcement resources” are valid motives for discretion. But the same action, “intended to evade the commitment,” is unlawful if premised on a “disagreement with the law being enforced.” It is not the case that “any deliberate deviation. . . is presumptively forbidden.”[52] Rather, the deviation must be done in bad faith, as an intentional means to bypass the legislature. The duty of the Take Care clause applies, “regardless of [the President’s] own administration’s view of its wisdom or policy.”[53]

Burton’s conclusion provides further insights into the Committee of Style’s decision to amend the Take Care clause. First, the Committee eliminated the reference to “duly.” Here, the framers moved away from focusing on what obligations the President owes to the Congress. Instead, they focused on “faithfully” alone. This inquiry directs attention to the President’s motivations, instead of the legal obligations to Congress in the abstract. The important qualification of “faithfully” vests the President with additional discretion, so long as he is acting with good faith.