A lot of ink has been spilled about the phrasing of the Questions Presented in the Same-Sex Marriage Cases. The first question asks “1) Does the Fourteenth Amendment require a state to license a marriage between two people of the same sex?” I think a necessary antecedent question is whether state is required to license marriage altogether. Marriage, understood in terms of a license, is in every sense a positive right. Unlike, say, Lawrence which protected the right to engage in sodomy, or Griswold, which protected the right of married couples to access contraceptive, the same-sex marriage cases are seeking that the state recognize unions with a license, and confer other positive benefits.

How is it, that the issuance of a piece of paper and certain entitlements could be a fundamental right? There is precedent to support this position–although I don’t think those cases carry such weight. Let’s start with Myer v. Nebraska (by everyone’s favorite Justice McReynolds) which lists the “right to marry” among other liberties protected by the 14th Amendment:

While this Court has not attempted to define with exactness the liberty thus guaranteed, the term has received much consideration and some of the included things have been definitely stated. Without doubt, it denotes not merely freedom from bodily restraint but also the right of the individual to contract, to engage in any of the common occupations of life, to acquire useful knowledge, to marry, establish a home and bring up children, to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience, and generally to enjoy those privileges long recognized at common law as essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.

Arguably, all of these rights are negative right–the liberty to be free from some sort of governmental restraint. Marriage, if we understand it to mean the granting of a government license, does not fit in with this list. Ejusdem generis. I had always understood McReynolds to use “to marry” as the right to cohabitation (certainly men and women, and perhaps even those of the same race). Marriage, as a positive right, does not fit in with the rest of the liberties McReynolds listed, except to the extent we are discussing a “common law” marriage.

Second, consider Skinner v. Oklahoma ex rel. Williamson. It discusses marriage in the context of procreation, in the absence of state infringement :

We are dealing here with legislation which involves one of the basic civil rights of man. Marriage and procreation are fundamental to the very existence and survival of the race. The power to sterilize, if exercised, may have subtle, far-reaching and devastating effects. In evil or reckless hands, it can cause races or types which are inimical to the dominant group to wither and disappear. There is no redemption for the individual whom the law touches.

Here Justice Douglas–who was very familiar with marriage licenses, having received quite a few himself–wasn’t referring to a positive right of marriage, but a negative right that the government cannot restrain the liberty interest of families. Recall Skinner concerned mandatory sterilization of prisoners–one of the greatest possible infringements on liberty imaginable. Indeed, Douglas’s decision in Griswold tied the right to contraception to those already married (Roe discarded this limitation).

Third, consider Justice White’s concurring opinion in Griswold v. Connecticut. His understanding of Myer, Pierce, and Skinner was premised on a negative conception of liberty–the state cannot infringe on the intimacies of family life.

It would be unduly repetitious, and belaboring the obvious, to expound on the impact of this statute on the liberty guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment against arbitrary or capricious denials or on the nature of this liberty. Suffice it to say that this is not the first time this Court has had occasion to articulate that the liberty entitled to protection under the Fourteenth Amendment includes the right “to marry, establish a home and bring up children,”Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390, 399, and “the liberty . . . to direct the upbringing and education of children,” Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510, 534-535, and that these are among “the basic civil rights of man.” Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535, 541. These decisions affirm that there is a “realm of family life which the state cannot enter” without substantial justification. Prince v. Massachusetts, 321 U.S. 158, 166. Surely the right invoked in this case, to be free of regulation of the intimacies of [p503] the marriage relationship, come[s] to this Court with a momentum for respect lacking when appeal is made to liberties which derive merely from shifting economic arrangements.

The entire nature of these precedents was keeping government out of private relationships. But modern day cases want to bring the government into these relationships to officially recognize them. (Libertarians in particular should be more cognizant of this point).

Fourth, this brings us to Loving v. Virginia, which was primarily an equal protection case. Then, at the end, Chief Justice Warren added a two-paragraph long Part II focusing on whether a fundamental right was violated. Here is the section, in its entirety:

These statutes also deprive the Lovings of liberty without due process of law in violation of the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The freedom to marry has long been recognized as one of the vital personal rights essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.

Marriage is one of the “basic civil rights of man,” fundamental to our very existence and survival. Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535, 541 (1942). See also Maynard v. Hill, 125 U.S. 190 (1888). To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications embodied in these statutes, classifications so directly subversive of the principle of equality at the heart of the Fourteenth Amendment, is surely to deprive all the State’s citizens of liberty without due process of law. The Fourteenth Amendment requires that the freedom of choice to marry not be restricted by invidious racial discriminations. Under our Constitution, the freedom to marry, or not marry, a person of another race resides with the individual, and cannot be infringed by the State.

When I teach this case, students are always confused about whether it is a due process inquiry or equal protection inquiry. Their confusion is justified, as Warren’s muddled opinion blurs the two beyond recognition.

First, the analysis effectively says because the ban on interracial marriage violates equal protection, it also violates due process. It speaks of “racial classifications,” “principles of equality,” and “invidious racial discriminations,” as the factors to suggest it deprives “citizens of liberty without due process of law.” If I had to guess, I suspect the Court added this as a throwaway to bolster the burgeoning due process jurisprudence from Griswold two years earlier–but this is mere speculation.

Second, the last sentence is not complete. The decision to cohabit with another “resides with the individual” for sure. This was the sort of right at issue in Myer or Skinner. This fits in with Justice White’s understanding of these precedents in Griswold. There was nothing in the law that prohibited the Lovings from living together. What they sought was not just to live together, but to have the state recognize that union with a marriage license. Or in other words, provide them with equal protection of the laws. Virginia would give marriage licenses to people of the same race, but not different races. This is indeed an invidious racial discrimination, that violates the equal protection clause. But nothing in the Court’s analysis explains why the marriage license itself–citations to Skinner are unhelpful–is a due process liberty interest, when it is separate and apart from negative rights like procreation and cohabitation.

In the past two years, numerous courts have dutifully cited Loving’s conclusion that a marriage license is a fundamental right regularly. Much of the criticism of these citations is that when the Court wrote Myer or Skinner or Loving, it meant that marriage was a union between a man and a woman. My criticism is different. Myer and Skinner discussed marriage in the negative context of procreation and raising a family–not as a positive right to petition the state for a marriage license. Loving added that gloss, without any analysis. Arguably Loving supports those citations, but Myer and Skinner do not.

None of this is to say that in June, the Court will decline to recognize marriage as a fundamental right. Perhaps due to evolving standards of decency, or modern conceptions of the dignity inherent in receiving state recognition of a union, there is a due process right to obtain a marriage license. But citations to Myer, Skinner, and even Loving need to add a modern-day gloss to carry the burden.

However, this gloss will raise serious complications if, after the Court finds a due process violation, states vote to give no one marriage licenses. If the phrasing of the Court’s first question presented is taken seriously, then a state cannot eliminate the licensure of marriage altogether, as that would violate the 14th Amendment. If this is a fundamental right, states would be required to hand out the licenses.

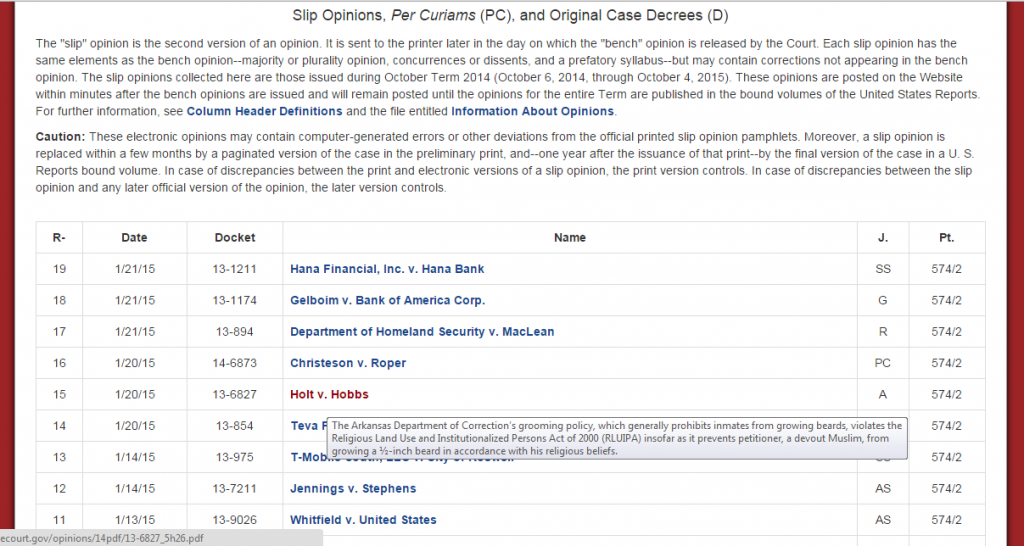

Oklahoma (the home of Skinner!) is proposing a bill that would prevent any state official, including judges or clerks, from performing marriage ceremonies. Further, the state would not issue any state-issued marriage licenses. Instead couples can file “marriage certificates” or “common law marriage certificates” with the clerk. Marriage would exist largely outside the state. This would seem to run afoul of the first question presented in the same-sex marriage cases. All the attendant benefits of marriage would remain, but the state would not be complicit in issuing any licenses to decide who is married.

Would such a law be constitutional? If indeed the Court holds that marriage is a fundamental right–not just that denying same-sex couples a license violates the equal protection clause–Oklahoma would be required to issue marriage licenses.

As I noted in an earlier post, this will be a much tougher opinion to write than people suspect. Circuit courts can gloss over these tough issues, but the Supreme Court cannot. They ducked the hard issues in Lawrence and Windsor. In the former, most stated had already eliminate sodomy statutes from the books, and those that had them on the books almost never enforced them. In the latter, invalidating the federal DOMA allowed the states to operate as they had before. But this case directly impacts laws that are feverishly contested in a majority of the states. I’ve been wrong about virtually every prediction I’ve made with the same-sex marriage cases, so I make no prediction, other than that the Court will surprise us.