If a person openly and notoriously walks across a piece of property daily for a certain period of time, and his claim of right is hostile to that of the owner of the property, he will gain a “prescriptive easement” to cross under the doctrine of adverse possession. That easement cannot be revoked. In fact, the squatter effectively takes a stick out of the bundle. This actually becomes a problem when you have privately owned sidewalks, where people are normally allowed to cross.

There are two ways to guard against these prescriptive easements.

One way is to acknowledge that the crossing is permissive. This vitiates the “hostility” or “claim of right” requirement for adverse possession. In other words, if I let you cross across my property, it is not hostile, and you cannot establish a prescriptive easement.

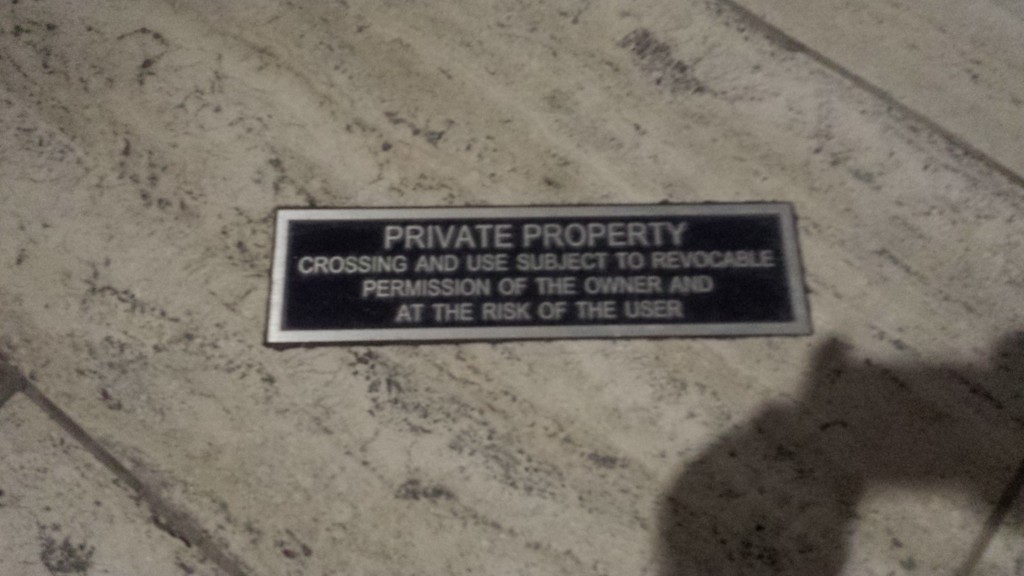

In Houston, the Shell Building on Louisiana has what appear to be privately-owned sidewalks. However, on each corner, bolted to the floor is this plaque:

This sign does exactly as I suggested–make clear that crossing the property is permissive, but it can be revoked at any time.

Private Property: Crossing and use subject to revocable permission of the owner and at the risk of the user.

This can also be interpreted as a license, which can be revoked at any time.

The other option is to simply shut the property down once a year, to defeat any possible claims to adverse possession. The Times profiles a property in New York that does just that.

In a practice dating to 1953 and a custom that can be traced to Anglo-Saxon England, RFR Realty, the building’s owner, will close the garden courtyard, arcade and interior sidewalks at Lever House, on Park Avenue between 53rd and 54th Streets, from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. on Sunday.

New Yorkers have quickly acquainted themselves with the concept of privately owned public space at Zuccotti Park. But there is another significant hybrid: purely private space to which the public is customarily welcome, at the owners’ implicit discretion. These spaces include Lever House, Rockefeller Plaza and College Walk at Columbia University, which close for part of one day every year.

Property markers, like a plaque set into the pavement at Lever House, are a frequent giveaway that one is about to set foot on someone else’s land. It reads, “Crossing and use subject to permission of the owner and at the risk of the user.”

Owners close these properties annually to protect themselves against any possible claim of “adverse possession,” a concept with ancient roots. It holds — to put it simply — that if someone openly and notoriously uses another’s property for a long period without ever being challenged by the rightful owner, the property becomes that of the possessor. Think of a farmer using an out-of-the-way corner of a neighbor’s acreage to pasture sheep for a generation or two, without the neighbor ever objecting.

Annual closings are how modern owners assert their dominion (as opposed, say, to killing someone’s sheep, or hauling him up before the folkmoot assembly).

Lever House has been closing itself once a year since 1953, when it was the brand-new headquarters of Lever Brothers. On Sunday, temporary barricades are to be erected, bearing signs saying: “This area is closed to public use on behalf of and in the name of the owner.” Some time later, an employee who was present will sign an affidavit attesting to the closing.