The Marshall Project reports on the death of Dollree Mapp, the eponymous defendant of the landmark decision in Mapp v. Ohio.

The woman behind the ruling, Dollree “Dolly” Mapp, died six weeks ago in a small town in Georgia, with virtually no notice paid. She was 91, as best we can tell.

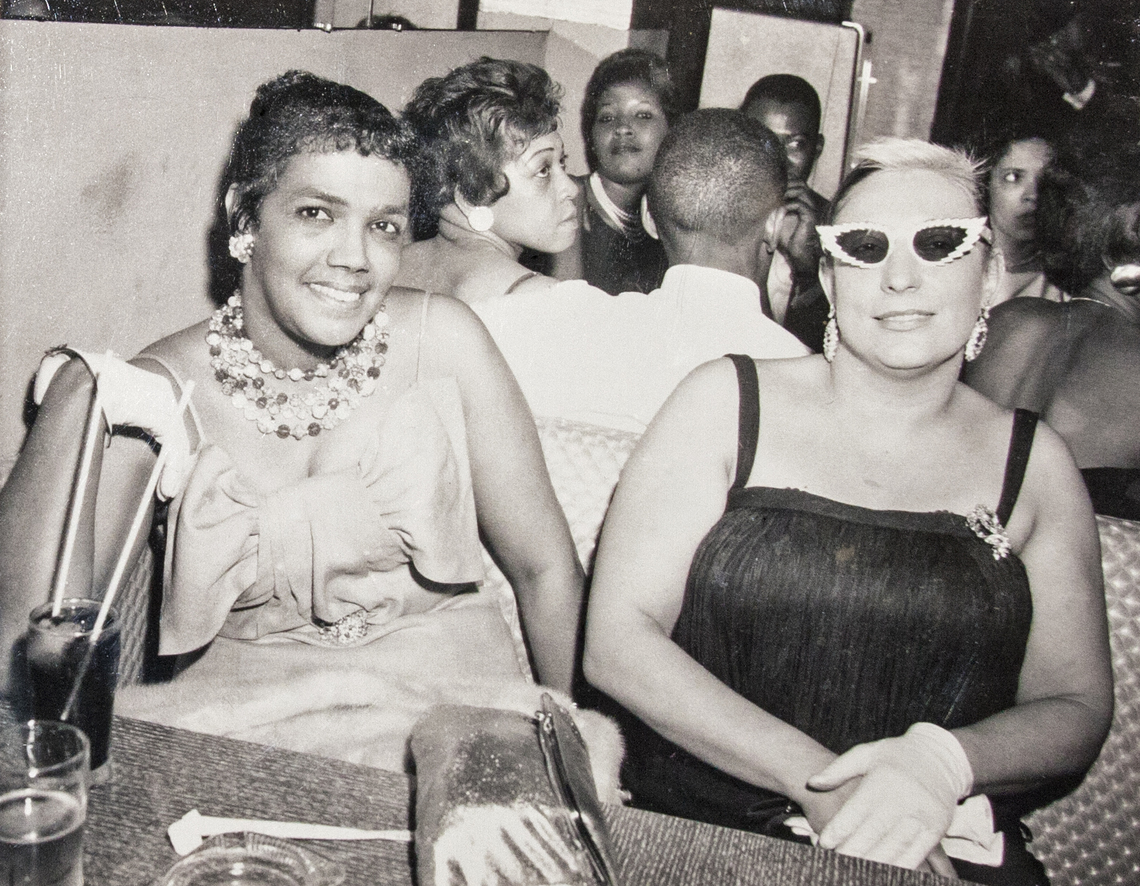

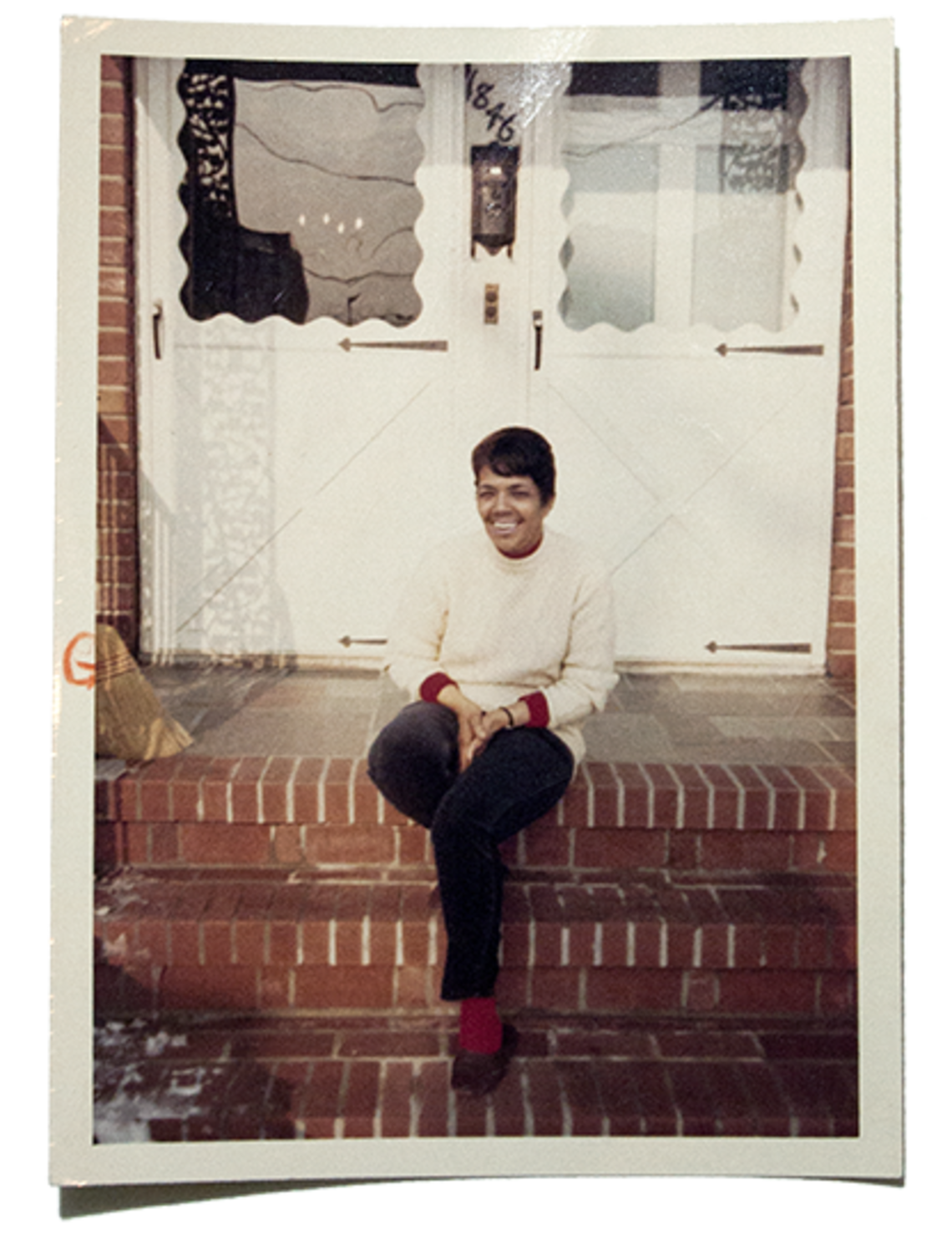

Mapp’s life was as colorful and momentous as her death was quiet. She went from being a single teenage mother in Mississippi to associating with renowned boxers and racketeers in Cleveland to making her way in New York City, where she launched one business after another. “Some of them were legitimate, and some of them were whatever they were,” said her niece, Carolyn Mapp, who looked after her aunt in her final years. Along the way she tangled with police, and when she stood up to them in Cleveland – a black woman, staring down a phalanx of white officers in the 1950s – she made history.

The obituary has a detailed account of the search of Mapp’s home.

In May of that year, police were investigating a bombing at the house of Don King – a numbers racketeer who later became a famed boxing promoter – when they received a tip that a suspect might be hiding in Mapp’s home. Three officers showed up at Mapp’s place, demanding to be let in. Mapp refused. She called a lawyer, who advised her to relent only if police produced a warrant. Even then, the lawyer told her, she should make sure to read it. About three hours later, the police, now between 10 and 15 in number, pried a door to force their way in. A lieutenant, waving a piece of paper, said they had a warrant. Mapp asked to see it. The lieutenant told her no. So Mapp grabbed the paper from him and stuffed it down the front of her blouse. She would later testify to what happened next:

“What are we going to do now?” one of the officers asked.

“I’m going down after it,” a sergeant said.

“No, you are not,” Mapp told the sergeant.

But the sergeant “went down anyway,” grabbing the paper back and keeping Mapp from ever reading it. In years to come, she would say she suspected the paper was blank.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Mapp v. Ohio was that it was originally viewed as an obscenity prosecution, but the Court repositioned it as an exclusionary act case.

The police found the man they were looking for (although he was later cleared in the bombing). But the search didn’t end there. Led by the sergeant who had retrieved the dubious warrant – a man who would later say Mapp had “a swagger about her” – police searched every room, upstairs and down, rummaging through boxes and drawers. During this search they found a pencil sketch of a nude and four books considered obscene, with titles that included “Memoirs of a Hotel Man” and “Affairs of a Troubadour.” Mapp told police the materials belonged to a former roomer, for whom she had stored them. But she was charged under an Ohio law that made possession of obscene material a felony. At trial, Mapp testified that when an officer found the books, “I told him not to look at them, they might embarrass him.” The jury took 20 minutes to convict, after which Mapp was sentenced to up to seven years.

…In their initial consideration of the case all nine justices agreed that the obscenity law violated the First Amendment. But when Associate Justice Tom C. Clark drafted the majority opinion, he shifted the focus of the case to the Fourth Amendment, which prohibits unreasonable search and seizure. By the time Mapp’s case reached the Supreme Court, it had become clear that the police never had obtained a warrant to search Mapp’s home.

Update: The Times has this obituary, and manages to take a swipe at the Roberts Court:

The current chief justice, John G. Roberts Jr., was a lawyer in the Reagan administration in the 1980s and helped it attack the exclusionary rule through litigation, proposed legislation and other means. In 2009, he wrote the majority opinion in Herring v. United States, a 5-to-4 decision that upheld the conviction of Bennie D. Herring after a search led to his arrest on drug and weapons charges based on false information that he was the subject of a warrant.

Some of the rule’s supporters worry that it could be significantly weakened or abolished under the current court. Jeffrey Fisher, a professor at Stanford Law School, said the issue would most likely go before the high court again as Herring is interpreted by lower courts.

“Some are reading Herring broadly,” Mr. Fisher said, “and some narrowly.”