Last week when I was in Phoenix, I had the pleasure of having lunch with great company, including Clint Bolick of the Goldwater Institute, Tim Keller of the Institute for Justice, Jennifer Perkins of the Arizona Courts, and Jeffrey Singer, a surgeon and an adjunct scholar at Cato. During lunch, (no surprise), we got into a deep discussion of Obamacare, and Jeff surprised me with some stuff that I didn’t know. Primarily, what exactly was the extent to which people were being denied pre-existing conditions before Obamacare, and how could that issue have been addressed short of radically transforming our entire health care market.

Fortunately for all of us, Jeffrey cogently summarized his position in this NRO piece, titled “The ACA: A Train Wreck and a Lie” which I would encourage you to read.

Jeffrey explained that before HIPAA, people could pay an additional premium to ensure that their policies could not be cancelled for pre-existing conditions. Jeffrey explained this was in the fine print, and people may not have seen it, but 75% signed up for it.

Before 1996, if you purchased individual health insurance through a broker, you would have been offered a “guaranteed renewability” option. This would guarantee that your policy could not be canceled if you developed an expensive and chronic condition. The insurance company would also have to renew the policy on its anniversary date without charging a higher premium because of the chronic condition. This option was so popular that, by 1996, 75 percent of people buying individual health insurance also bought the guaranteed-renewability option.

But after HIPAA, all plans had to offer this option.

Then, in 1996, Congress passed the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Among HIPAA’s many mandates was the requirement that all individual insurance plans have guaranteed renewability. It also prohibited all group health-insurance plans sold to businesses from denying coverage to individuals because of preexisting conditions.

And so, for the past 18 years, all insurance companies have been legally forbidden from dropping an individual policyholder who developed a chronic illness and have not been able to raise anyone’s rate because of it.

But there was a small percentage of the population, for reasons Jeff describes, who fell through the cracks, and did have policies cancelled. How many? In short, roughly 1% of Americans were actually affected by this serious problem.

Yet a major goal of the ACA supposedly was to address the problem that some people couldn’t obtain insurance because they had preexisting conditions that rendered them either “uninsurable” or insurable only for an unaffordable premium.

These are people who do not already have individual or group health insurance and are not eligible for Medicare or Medicaid. An example would be someone who lost his job and his employer-provided insurance, has a chronic illness, and has exhausted his coverage under COBRA. Just what percentage of the non-Medicare/non-Medicaid population could have this problem? According to a 2001 survey by the Department of Health and Human Services, corroborated by other academic studies, just 1 percent of the under-65 population has ever been denied health insurance.

This 1% is dwarfed by the 5% who have now had their plans cancelled:

Ironically, the president tried to minimize the failure of his “like your plan, keep your plan” pledge by arguing, “We’re talking about 5 percent of the population.” In his State of the Union, he didn’t mention the 5 percent, which comes out to approximately 5.4 million Americans, who had their plans canceled because of the ACA. Instead, he patted himself on the back for helping free people from “substandard plans” that, he claims, would have dropped them if they developed some chronic and costly illness.

A problem that could have been fixed by direct subsidies to those affected was solved by a radical transformation of the entire health care system.

So to address a problem afflicting a minute portion of the under-65 population, Congress committed trillions of dollars to drop a nuclear bomb on the U.S. health-care system, remaking it in the image of your local DMV. For a tiny fraction of those trillions, Congress could have adopted one or more of the many alternative solutions to the problem faced by that small group of people, from the promotion of “health-status insurance” to the creation of viable high-risk pools.

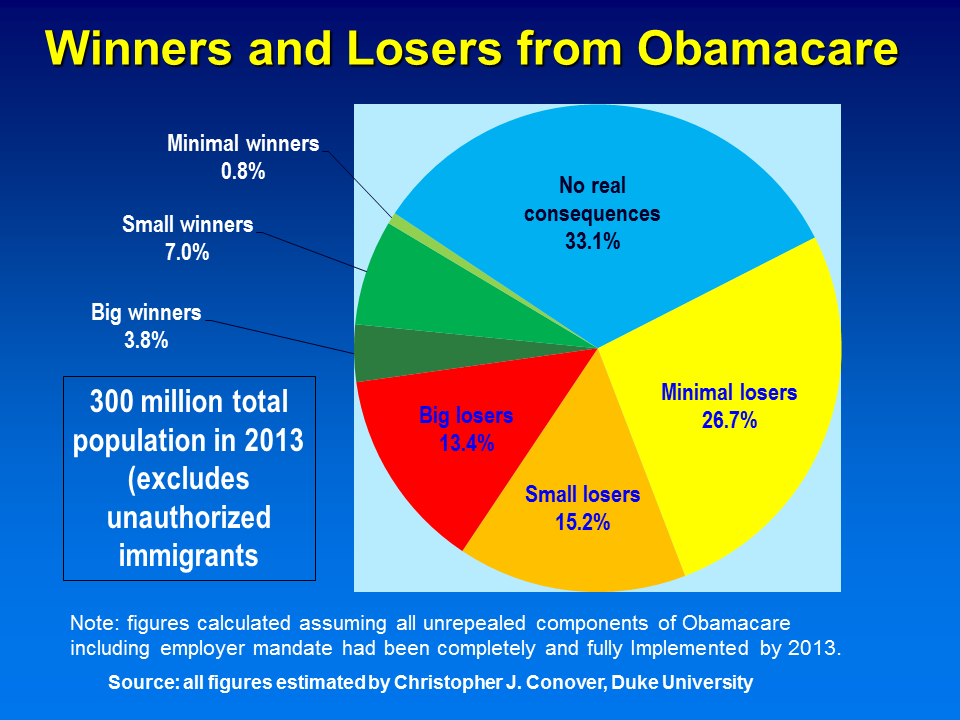

Chris Conover puts a finer point on this–for every one winner, there will be four losers. Read the entire post, but here is the conclusion:

When all is said and done, were Obamacare fully in place right now, 166 million of today’s population could reasonably count themselves as losers in various ways, while only 34.6 million would be lucky enough to count as winners. That’s a ratio of 4.8 losers for every winner–not a particularly good outcome for any policy initiative, much less a “signature” legislative initiative.

Even if we focus on big winners (11.4 million) vs. big losers (40.3 million) this imbalance does not change appreciably: there are 3.6 big losers for every big winner. Similarly, if we ignore “minimal” winners and losers, there’s still 2.7 remaining losers for each remaining winner. No matter how we slice and dice the results, the conclusion challenges the conventional wisdom of the law’s proponents. Losers actually vastly outnumber winners regardless of which definition is used.

Conover adds:

Prof. Gruber argues “no law in the history of America makes everyone better off.” But as fellow Forbes contributor Dr. Scott Gottlieb put it in a recent Intelligence Squared debate, “We didn’t have to hurt some people to help some people in this country, but that’s precisely what we did.” In light of the likely impacts of Obamacare codified in my chart, but I think reasonable people can wonder whether a law tilted so sharply in the direction of making so many Americans worse off rather than better off really is a good idea. I think these figures validate the persistent opposition of the public towards this law since well before its enactment and make the continued majority support for the law’s repeal quite understandable. When will proponents of the law finally listen to the public and concede this law is not working out as hoped?

I’ve commented before on the winners and losersof Obamacare. When this law was sold, many misrepresentations were made concerning who would benefit, and even more misrepresentations were made about who would be harmed (remember, if you like your plan you can keep it). As more and more people find that they are in fact worse of, the initial pitch of the law–and the President’s refusal to acknowledge at the State of the Union that *anything* is wrong becomes more significant to the future vitality of the law.

So where does that leave us. The most recent Kaiser Poll shows that, though 50% of Americans hold a negative ivew of Obamacare, 55% view it as “settled law that should be improved, rather than repealed.”

The survey found that 50 percent have a negative view of the Affordable Care Act, against only 34 percent who have a positive view. That’s the same negative margin from November, but up slightly from December, when 48 percent had a negative view vs. 34 percent positive.

However, a strong majority – 55 percent – said they accept ObamaCare as settled law that should be improved, rather than repealed. Only 38 percent said they support continued efforts to repeal it.

I think this states the obvious. Obamacare, by itself, can’t be repealed. The efforts at repealing the law were largely political theater–though, political theater did have one very important consequence. It kept the spotlight shined bright (like a diamond!) on the flaws of Obamacare, and paved the way to substantial changes in the future. The scope of the improvements, and how the GOP (and vulnerable Democrats) advance them in the next two years, will likely define the battle over Obamacare.