Nicole Huberfeld is one of the top scholars on health law, and submitted a key brief that was cited passim by Justice Ginsburg in the Medicaid portion of the opinion. I turned to her for all of my tough health-wonk question while writing Unprecedented.

Nicole has posted a new piece on SSRN (which we discussed briefly at a recent conference) titled Dynamic Expansion, that offers some early observations about how states that have not opted into the Medicaid expansion. Nicole contends that these Republican governors, with a few exceptions (Texas) are leaning towards implementation. She observes this undercuts the Court’s federalism explanation.

Here is the abstract:

In the run up to the ACA’s effective date of January 1, 2014, the sleeper issue has been the Medicaid expansion, even though Medicaid stands to cover nearly a quarter of the United States citizenry. While the national press has portrayed a bleak picture that only half of the states will participate, the Medicaid expansion is progressing apace. Though this thesis may sound wildly optimistic, it is more than predictive; it is empirically based. I have gathered data on the implementation of the Medicaid expansion during the crucial months leading up to the operation of the insurance provisions of the ACA, and it is clear that most states are moving toward expansion, even if they are currently classified by the media as “not participating” or “leaning toward not participating.” The data thus far reveals counterintuitive trends, for example that many Republican governors are leading their states toward implementation, even in the face of reticent legislatures and a national party’s hostility toward the law. Further, the data demonstrates dynamic negotiations occurring within states and between the federal and state governments, which indicates that the vision of state sovereignty projected by the Court in NFIB v. Sebelius was incorrect and unnecessary.

And from the essay on the federalism point:

Somewhat paradoxically, this analysis exposes the Supreme Court’s aggrandizement of its own power to police the line of authority between the federal government and the states in the name of state sovereignty. In NFIB v. Sebelius, the Court cast its role as protecting states from coerced participation in the expansion of Medicaid initiated by the ACA. To so protect state sovereignty, the Court limited HHS’s authority to penalize states for failure to participate in the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid, effectively permitting states to opt-in or opt-out of the Medicaid expansion. To arrive at this conclusion, the Court proclaimed that the Medicaid expansion was a new program, separate and apart from existing Medicaid. I have described elsewhere why this legislative interpretation does not hold water;31 here, I add to that analysis by observing that the Medicaid Act has always given the Secretary of HHS authority to waive state compliance with the Medicaid Act. In other words, even though Congress did not write new Medicaid waivers into the expansion provisions of the ACA, it did not need to, because states have had power to seek waivers since the Medicaid Act was passed in 1965. In fact, section 1115 waivers were created in 1962 as an amendment to the Social Security Act.32

Thus, the Court did not create this seemingly new ability for states to negotiate waivers with HHS in NFIB v. Sebelius; it existed all along in the “old” Medicaid Act, and it is being used to implement the Medicaid expansion in the very states that are reported as rejecting the expansion. The new and undefined coercion doctrine did not need to be articulated. This dynamic execution of the Medicaid expansion will take time to fully reveal itself, but the pattern that is coming into focus is quite different from the fragile state sovereignty depicted by the Court.

In other words, because this waiver system was baked into Medicaid, the Court did not need to create a new constitutional doctrine.

This may be how Medicaid was structured, but this was not how HHS comported itself during the NIFB litigation. They did not give the states any option to “negotiate.” Even before the Supreme Court, HHS refused to disclaim the power to unilaterally withdraw all funding (I agree with Nicole that there was no difference between the “old” and “new” funding but everyone at One First St. seemed to accept that distinction).

As I discuss in Unprecedented, and in this post, the Solicitor General was unable to impress on HHS the necessity of saying Arizona need not lose all of its funding. In sum, Sebelius would not allow Verrilli to make this point. HHS had sent the letter to Arizona, which did not reflect any possible negotiation, and HHS would not repudiate this position before the Court.

I excerpt the post here:

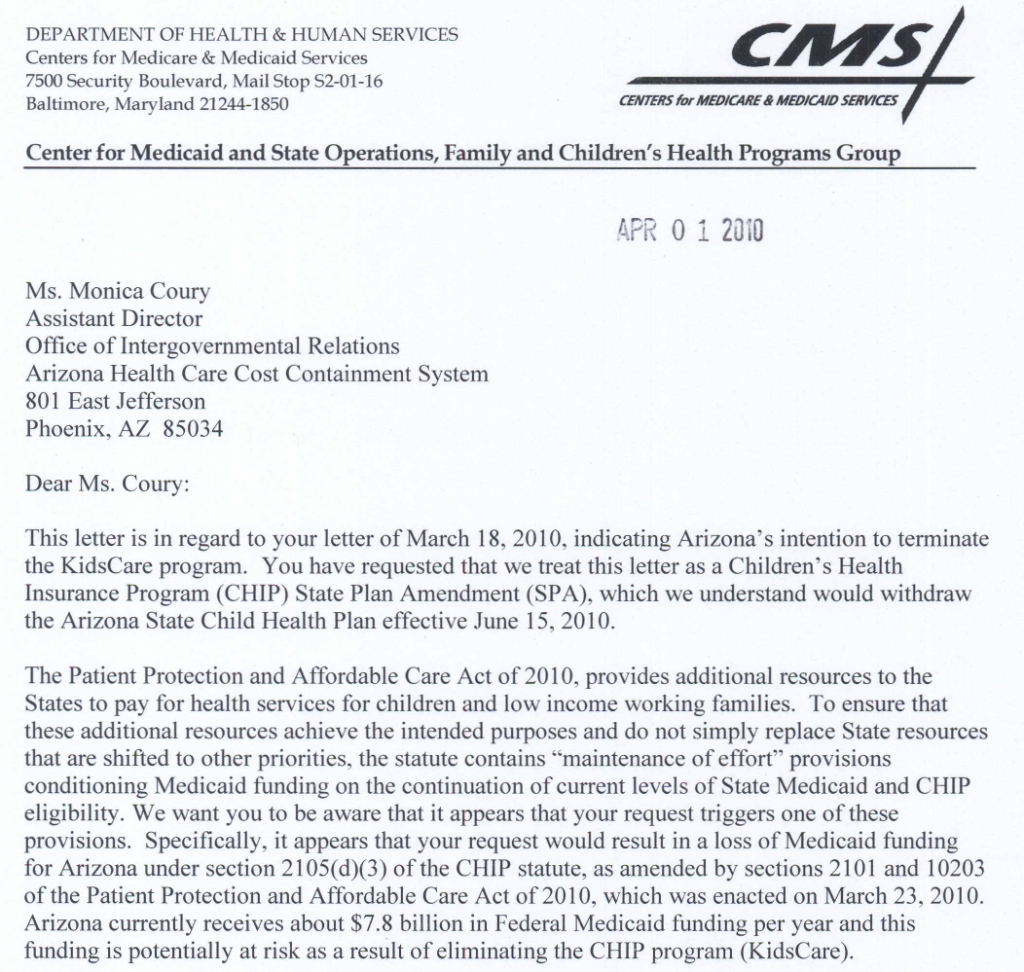

Five days before the Affordable Care Act was signed into law Jan Brewer notified the Department of Health and Human Services that it intended to terminate its participation under the KidsCare program. This program, commonly known as CHIP, was one aspect of the Affordable Care Act’s expansion that provided additional funding to the states to provide health insurance for children.

One week after the Affordable Care Act became law, HHS responded with an ominous and pointed letter: “In order to retain the current level of existing funding, the state would need to comply with the new conditions under the ACA.” This observation was followed by a warning: “We want you to be aware that it appears that your request . . . would result in a loss of [all] Medicaid funding for Arizona.” If Arizona opted out of CHIP, it could stand to lose almost $8 billion in Medicaid funding. That would probably obliterate the state’s budget.

The HHS letter to Arizona contained a not-too-veiled threat of what would happen to other states that did not go along with the Affordable Care Act’s expansion of Medicaid funding. To Arizona, there was no real choice.

Though this letter was not attached as an exhibit to the Supreme Court briefings, and had only been referenced in a single footnote in a motion submitted to Judge Vinson in district court in Florida, Paul Clement mentioned it at just the right moment during oral argument.

Citing this letter, Clement told the Court that what made this expansion so coercive was that Congress was tying “the states’ willingness to accept these new funds . . . to their entire participation in” Medicaid. In other words, turning down the new funds would result in opting out of the entire program, including the old funds.

The Solicitor General was pressed on this letter repeatedly by Justices Roberts, Kagan, and Breyer. All three wanted to know whether the Secretary would in fact take away all of a state’s funding for not participating in the expansion. Verrilli would not state whether HHS maintained that they had the power to revoke all funds, only saying that she would not exercise this power.

Justice Breyer, noting that Clement had said that the secretary “would do it” and withdraw the funding, asked “I would like a little clarification.” Then, Justice Scalia asked if the secretary had the power to withdraw the funding. Verrilli, begrudgingly admitted that “it is possible.” But, he continued, “I’m not willing to give that away.” In other words, he would not concede that fact.

Kagan would not accept that and asked why Verrilli was not “willing to give [that] away.” Breyer chimed in. “What’s making you reluctant?” Verrilli, with a slight chuckle, replied, “I’m not trying to be reluctant.” He chuckled because he knew from the outset that he was not going to answer the question posed to him.

Scalia interrupted him. “I wouldn’t think that is a surprise question.” The solicitor general was not unprepared. Rather, the United States made a conscious choice not to answer the question. He told the justices, “I’m trying to be careful about the authority of the secretary of Health and Human Services and how it will apply in the future.” Verrilli represented the interests of the United States. He could not pin the government into a position that would bind it in the future. More precisely, HHS would not give that power up, so he could not make such a representation in Court. The Solicitor General lacked the authority to answer that question. Unfortunately, the letter, drafted over two years earlier–and likely not vetted by a full legal review–made this representation. Verrilli’s evasion served to inflame the concerns of Roberts, Breyer, and Kagan—the very justices who would soon vote against him on the constitutionality of the Medicaid expansion. HHS would not disclaim that power, so the Court did it for them.

H/T Andy Koppelman.