My C.V. is available here. My FAR form is available here. I’ll keep you all posted.

All of my AALS materials are available here.

There is just tooo much irony here.

Zak Slayback is one of the star interns at the Harlan Institute. He wrote a really great piece on privatizing highways.

Yet the guise of competition continues as centralized planners auction off the rights to build their central plans. Furthermore, the signals sent via the price mechanism in a free market system allow the market to adjust to any changes much more quickly and efficiently than the current centrally-planned model under which we operate.

Knowledge is not something that can be aggregated and centrally-planned for a Department of Transportation bureaucrat to determine. Knowledge is something that must be acquired in small bits throughout the market, risks must be taken to acquire knowledge and no one man, or group of men for that matter, will posses the knowledge necessary to perfectly plan any specific endeavor. Why leave this, whatFriedrich Hayek, the Austrian economist and Nobel laureate, called the “knowledge problem”, to a group of individuals who are insulated from any signs and information translated to them via price signals? Major investments, especially those that require a large amount of information to property operate, such as highways, should be left to the system which best responds to market signals and the price mechanism: the free market.

Finally, there is a major moral issue at play when building any public works project, but especially highways: who pays for the highway and with what money? Under the current system, public works projects are paid for by the public. Who is “the public” and what gives moral authority to central planners to determine that all taxpayers in a given population should be forced to pay for the planners’ project? While it could be argued that public highways benefit an entire area, should those who decide against using the highway and its related infrastructure be forced to pay for it? This is perhaps the largest flaw with any argument favoring the public completion of Route 219. Using public funds to finish a highway that the entire public has not directly consented to is coercion.

The state is not some kind of benevolent deity that reaches out from Harrisburg or Washington and grants the public its own highways; the state must fund its creations, and because the state cannot create wealth, it must forcibly take this wealth from the populace. The French political economist Frederic Bastiat expands on this concept of destroyed wealth in his essay “What is Seen and What is Not Seen,” but he can be proficiently summed up in a simple quote: “everyone wants to live at the expense of the state. They forget that the state wants to live at the expense of everyone.”

Read it, and try to grasp that Zak is only 17. When I was 17 I had no idea who Hayek or Bastiat were. Really, unbelievable. Keep your eye on him.

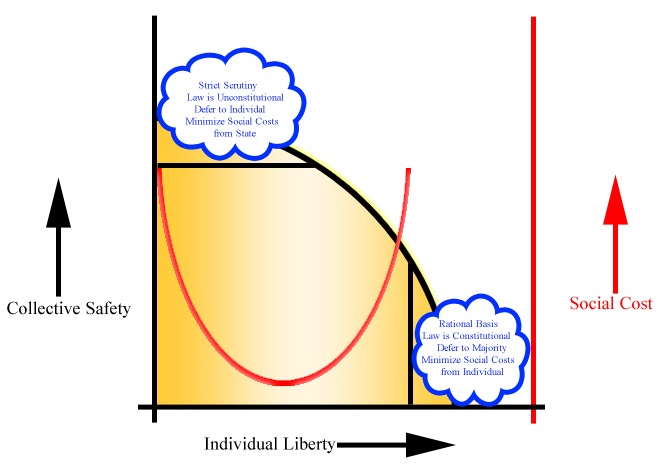

Benjamin Wittes has a great post at Lawfare reconsidering the meaning of two classic quotes from Ben Franklin (“Those who would give up essential Liberty, to purchase a little temporary Safety, deserve neither Liberty nor Safety”) and Robert Jackson (“There is danger that, if the [Supreme] Court does not temper its doctrinaire logic with a little practical wisdom, it will convert the constitutional Bill of Rights into a suicide pact.”) about liberty and security. Wittes argues that both Franklin and Jackson meant the opposite of what people usually understand these quotes to mean. Wittes’ remarks mirror my writings on judging the constitutionality of social cost (see here and here).

As I explained, Franklin was not describing some grave tension between government power and individual liberty, in which one necessarily yielded civil liberties when one empowered government to protect people. He was describing, rather, effective self-government in the service of security as the very liberty it would be contemptible to trade away. Notwithstanding the way the quotation has come down to us, Franklin saw the liberty and security interests he was describing as aligned with one another. . . . In other words, like Franklin, Jackson was actually denying a stark balancing of liberty interests and security interests and asserting an essential congruence between them. Indeed, he was criticizing the court for believing that liberty and order must exist in some precarious balance in which the protection of one came at the expense of the other.

Indeed. Given a society with too much liberty, there would be no security. As I noted in a previous post, assume the liberty interest is the right to have sex with whomever one chooses. Commenter AJ wrote, this example “may seem like the epitome of an individual liberty, but have I really ‘secured’ this if I’m in danger of being lynched by a mob that disapproves of my choice of partner? (to choose another historical example).” In my taxonomy, the social cost of too much liberty, with not enough security, makes such polices undesirable. In terms of scrutiny, these types of law would defer to the state’s interest, and be skeptical of the individual’s liberty interest.

Jackson’s critique of the court was that by denying authorities the ability to maintain minimal conditions of order, it was empowering people who disbelieved in both freedom and order. The suicide pact to which he refers is the choice of anarchy with neither liberty nor security over a regime of ordered freedom. That’s actually much more similar to than different from what Franklin was asking for. Both were, after all, arguing for the ability of local democratic communities to protect their security—and liberty—through self-government.

Though the flipside of this dynamic is that if the power of the state grows too large, where high social costs from government power diminish individual liberty, these policies are similarly undesirable, through application of the same logic of Franklin and Jackson.

First Amendment law has long-since passed by Jackson’s specific point about what sort of utterances should and should not trigger liability for their propensity to cause violence. But his larger point still stands. One doesn’t maximize either liberty or security at the other’s expense. It’s curious how two famous quotations that both invoke this complex the have both come to stand for precisely the zero-sum balancing that the speakers were rejecting.

Wittes concludes that liberty and security need not be a zero-sum game, where the increase in one results in the decrease of another. This dynamic is reflected in the Posner/Vermeuel curve where liberty and security can be varied independently when a policy exists below the social cost frontier.

In this orange-shaded region, liberty and safety can be varied without affecting each other. Considering the Posner/Vermeule curve, a change from policy Q* to Q results in an increase in individual liberty without a concomitant decrease in security. Likewise, a change from policy R* to R results in an increase in security without a concomitant decrease in liberty. With these policies, liberty can be increased without decreasing safety, and safety can be increased without decreasing liberty. As the authors noted, “[o]f course, not every issue of security policy presents such a tradeoff. At certain levels or in certain domains, security and liberty can be complements as well as substitutes. Liberty cannot be enjoyed without security, and security is not worth enjoying without liberty.”

Apparently the Times keeps track of the number of times someone looks up a word, and how often that word is used. Here are the top 50. How many do you know?

H/T Gizmodo