In Terror in the Balance, Eric Posner and Adrian Vermeule introduce a “tradeoff thesis” to explain how courts balance between security and liberty in times of criss. To illustrate this tradeoff, the authors produced a “security-liberty frontier” (Figure 1 on page 2) that is similar to a Pareto frontier (like the Guns and Butter curve from Econ 101).

In Terror in the Balance, Eric Posner and Adrian Vermeule introduce a “tradeoff thesis” to explain how courts balance between security and liberty in times of criss. To illustrate this tradeoff, the authors produced a “security-liberty frontier” (Figure 1 on page 2) that is similar to a Pareto frontier (like the Guns and Butter curve from Econ 101).

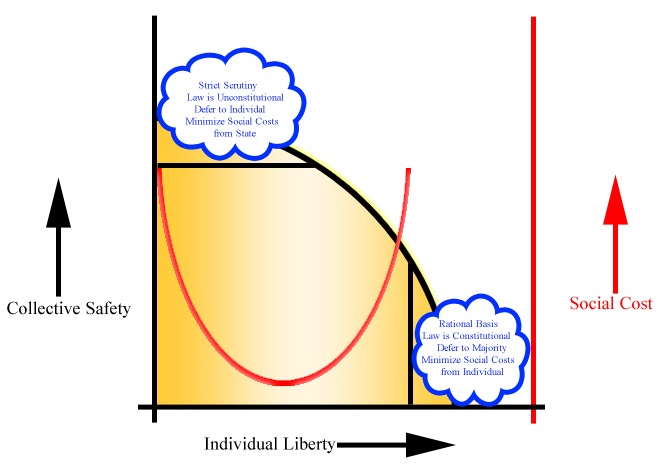

On the X-Axis is Liberty. On the Y-Axis is Security–the ability of the state to protect the people–in the context of their book, from terrorism. On the frontier (the curve) “any increase in security will require a decrease in liberty, and vice versa.” This curve rejects any claims that “liberty is priceless” or “security at all costs.”

Posner and Vermeule use this curve to illustrate how the relationship between security and liberty can be used to “maximize the aggregate welfare of the population”–“[b]oth security and liberty are valuable goods that contribute to individual well-being or welfare. Neither good can simply be maximized without regard to the other.” The authors note that the frontier by itself “conveys no information about where the optimal tradeoff point lies.” Rather that point “depends entirely on the values or preferences of the people in the relevant society.” Effectively, the frontier “represents a constraint on the opportunities available to governments.” The shape of the Frontier is not static–“balance between security and liberty is constantly readjusted as circumstances change”

A valuable contribution of the Frontier model is that it allows people to recognize that “security and liberty are comparable” and “can make judgments about the relative worth, to them, of increases (decreases) in security that produce a concomitant decrease (increase) in liberty.” However, this is not to say that all increases in liberty will result in a decrease in security, or that all increases in security will result in a decrease in liberty. An important aspect of this model is the recognition that certain government policies can reside below the curve (Points Q, Q*, R, and R*), where liberty and security are not directly related.

The Posner/Vermuele frontier is helpful in order to illustrate the relationship between liberty, social costs, and security I discussed in The Constitutionality of Social Cost (which is now in print in the Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy). I adapted this frontier, with a few alterations, in what I call the Social Cost Frontier. I re-labeled the X-Axis as individual liberty, rather than liberty. This focuses on what is implicit in Posner and Vermuele’s analysis–liberty inures to the benefits of individuals, while security inures to the benefit of society, at large (and these two factors are often at odds). I re-labeled the Y-Axis more broadly as Collective Safety–security is really a subset of collective safety. The red curve represents social cost (and corresponds to a second axis on the right, labeled social cost).

The Posner/Vermuele frontier is helpful in order to illustrate the relationship between liberty, social costs, and security I discussed in The Constitutionality of Social Cost (which is now in print in the Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy). I adapted this frontier, with a few alterations, in what I call the Social Cost Frontier. I re-labeled the X-Axis as individual liberty, rather than liberty. This focuses on what is implicit in Posner and Vermuele’s analysis–liberty inures to the benefits of individuals, while security inures to the benefit of society, at large (and these two factors are often at odds). I re-labeled the Y-Axis more broadly as Collective Safety–security is really a subset of collective safety. The red curve represents social cost (and corresponds to a second axis on the right, labeled social cost).

In The Constitutionality of Social Cost I defined the social cost as a negative externality that could result from the exercise of individual liberty (such as harm that could result from using a firearm for ill will). Effectively, the more liberty a person has, the more risk there is for the individual to cause social cost to society as a whole. In future works, I aim to broaden this definition to also include social cost that can result from the exercise of government power. Effectively, the more power the government has, the greater the risk of the state of causing social costs to individuals (and their liberties). The red social cost curve, represented by a parabola, illustrates this relationship.

This frontier helps to explain judicial review and the relationship between the tiers of scrutiny and social cost. Scrutiny is effectively a question of how much deference the courts will give–but deference to whom? Generally we think of rational basis scrutiny as the Court deferring to the determinations of the majority and exhibiting skepticism towards the individual’s liberty interest. Strict scrutiny, on the other hand, employs skepticism to the determinations of the majority, and deference to the individuals’ liberty interest. These determinations are linked with considerations of social cost.

High social costs from an individual that can harm society nudges the courts to show deference to society (majority rule) viz strict scrutiny. High social costs from government power that can harm individual liberty nudges courts to show deference to individuals (individual liberty) viz rational basis. In this sense, strict scrutiny and rational basis are mirror images of each other, reflected along the social cost curve. These mirror images are illustrated by the two clouds on the figure.

In the first cloud, which represents, strict scrutiny, courts will defer to individual liberty and be skeptical of the state’s power to provide for collective safety and minimize potential social costs from the state; as a result the law in question will likely not be upheld. Looking at the curve at this point, we see that the individual liberty interest is quite low, but the state’s power to provide for collective safety is quite high. Additionally, the social cost of the government’s power to the individual is also quite high (represented by the high point of the parabola). In these cases, where the social cost is too high, the protection of individual liberty is too low, and the power of the state is too high, courts are skeptical of the government’s power, and defer to the liberty interest. This is the essence of strict scrutiny, visualized.

In the second cloud, which represents rational basis scrutiny, courts will defer to the state’s power, and be skeptical of the liberty interest in order to minimize social costs from the individual; as a result, the law in question will likely be upheld. At this point, the social cost of the individual’s liberty can be quite high (represented by the high point on the parabola). In these cases, where the social cost is too high, the protection of the state’s safety is too low, and the liberty interest is too strong, courts are skeptical of that liberty interest, and defer to the majorities. This is the essence of rational basis, visualized.

The symmetry between the two ends is illustrated by the model–striking down a law and deferring to individuals is the opposite of upholding a law and deferring to the state. In this sense, the Court can be both a majoritarian and counter-majoritarian/libertarian institution depending on the level fo social costs.

Both strict scrutiny, and rational basis, attempt to guard the Social Cost Frontier, and keep the law below the curve, in the orange-shaded region. The cases at the margin–along the curve–are often the toughest to decide. The Supreme Court, as an institution, has assumed the role of policing these cases, and making sure that border is seldom reached by nudging cases down.

In this orange-shaded region, liberty and safety can be varied without affecting each other. Considering the Posner/Vermeule curve, a change from policy Q* to Q results in an increase in individual liberty without a concomitant decrease in security. Likewise, a change from policy R* to R results in an increase in security without a concomitant decrease in liberty. With these policies, liberty can be increased without decreasing safety, and safety can be increased without decreasing liberty. As the authors noted, “[o]f course, not every issue of security policy presents such a tradeoff. At certain levels or in certain domains, security and liberty can be complements as well as substitutes. Liberty cannot be enjoyed without security, and security is not worth enjoying without liberty.”

In anticipation of comments, Vermuele does a very thorough job of responding to a number of criticisms (I expect to receive) with respect to plotting liberty and security on a graph in this paper. Most saliently, the frontier, has its limitations–it is “not an empirical claim about security policy,” nor does it aim to “evaluate, on the merits, whether” certain policies are optimal, but rather serves as only an “expository device.” For example, Posner and Vermuele conceded that the concept of individual liberty is “more difficult to determine,” so they “basically have to ignore it.” Viewed in this limited fashion, and putting aside objections about representation of these items on a graph, the explanatory features of this model are quite illustrative of how courts approach judicial review.

Cross-Posted at ConcurringOpinions.com.