There is perhaps no more reviled figure in Supreme Court lore than Chief Justice Roger Taney. His decision in Dred Scott, filled with unthinkably racist language, went out of its way to resolve the case on as broad grounds as possible. Rather than simply dismissing the case for lack of diversity jurisdiction, he purported to find that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional, it would violate due process for the federal government to eliminate slavery, and that free states could not actually confer constitutional citizenship onto Africans so that they would be entitled to the Article IV “privileges and immunities” of citizenship.

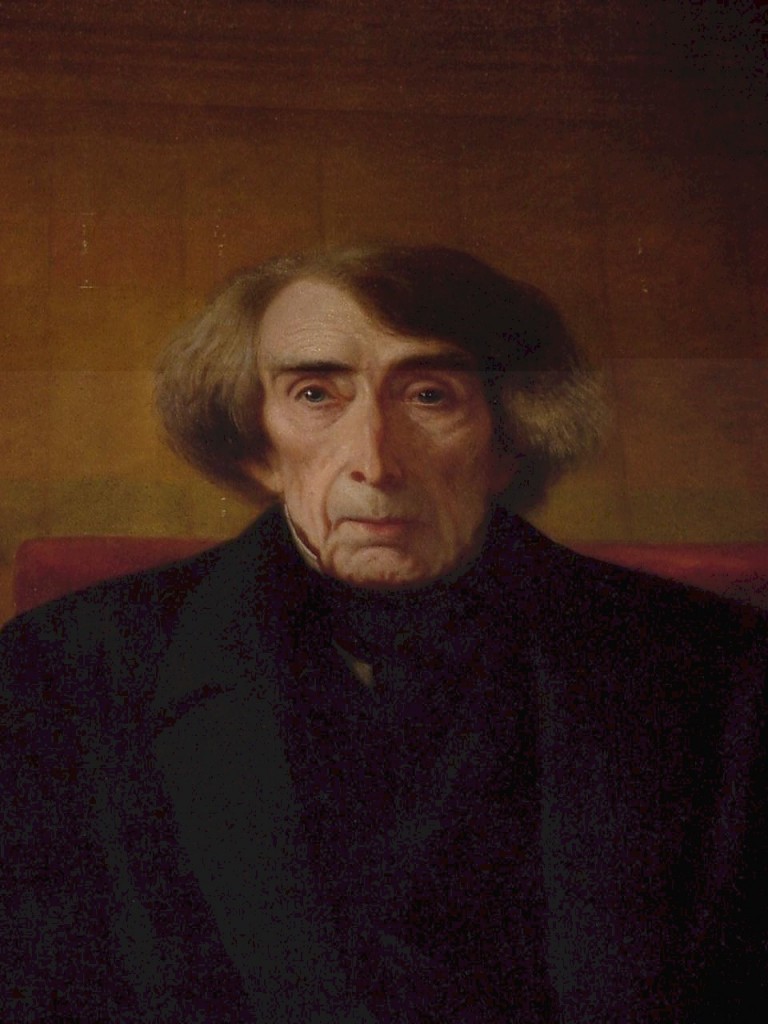

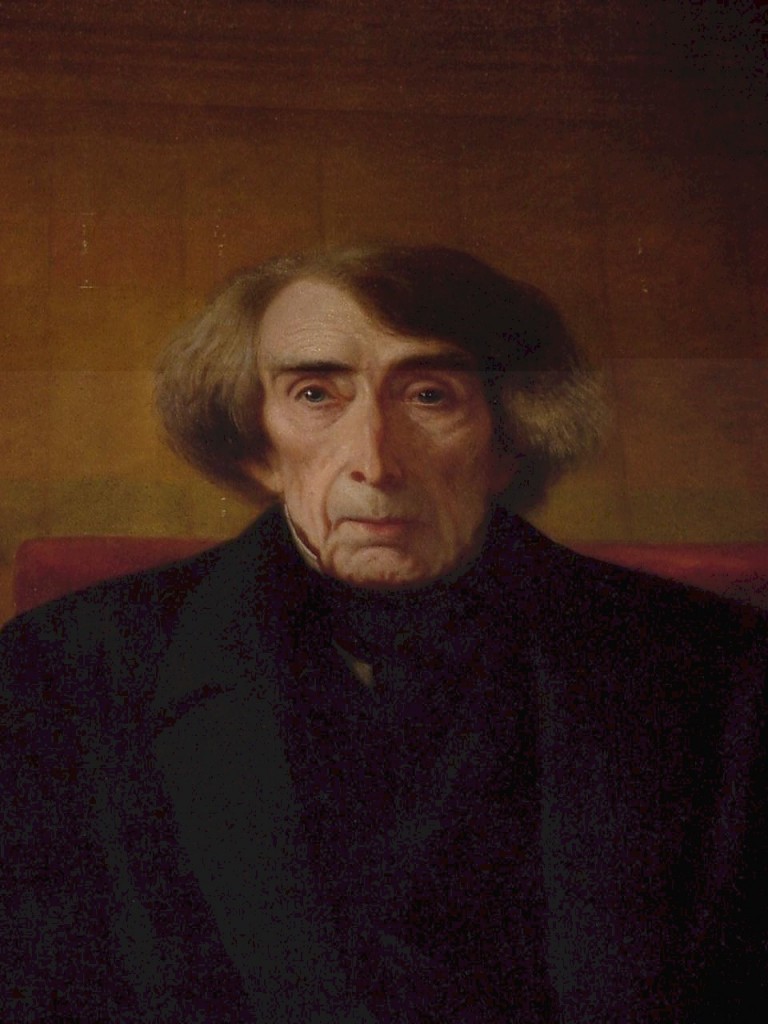

When most of us visualize Taney, we think of the portrait that hangs at Harvard Law School, which Justice Scalia described in vivid langauge in his Planned Parenthood v. Casey dissent.

When most of us visualize Taney, we think of the portrait that hangs at Harvard Law School, which Justice Scalia described in vivid langauge in his Planned Parenthood v. Casey dissent.

There comes vividly to mind a portrait by Emanuel Leutze that hangs in the Harvard Law School: Roger Brooke Taney, painted in 1859, the 82d year of his life, the 24th of his Chief Justiceship, the second after his opinion in Dred Scott. He is all in black, sitting in a shadowed red armchair, left hand resting upon a pad of paper in his lap, right hand hanging limply, almost lifelessly, beside the inner arm of the chair. He sits facing the viewer, and staring straight out. There seems to be on his face, and in his deep set eyes, an expression of profound sadness and disillusionment. Perhaps he always looked that way, even when dwelling upon the happiest of thoughts. But those of us who know how the lustre of his great Chief Justiceship came to be eclipsed by Dred Scott cannot help believing that he had that case–its already apparent consequences for the Court, and its soon to be played out consequences for the Nation–burning on his mind. I expect that two years earlier he, too, had thought himself “call[ing] the contending sides of national controversy to end their national division by accepting a common mandate rooted in the Constitution.”

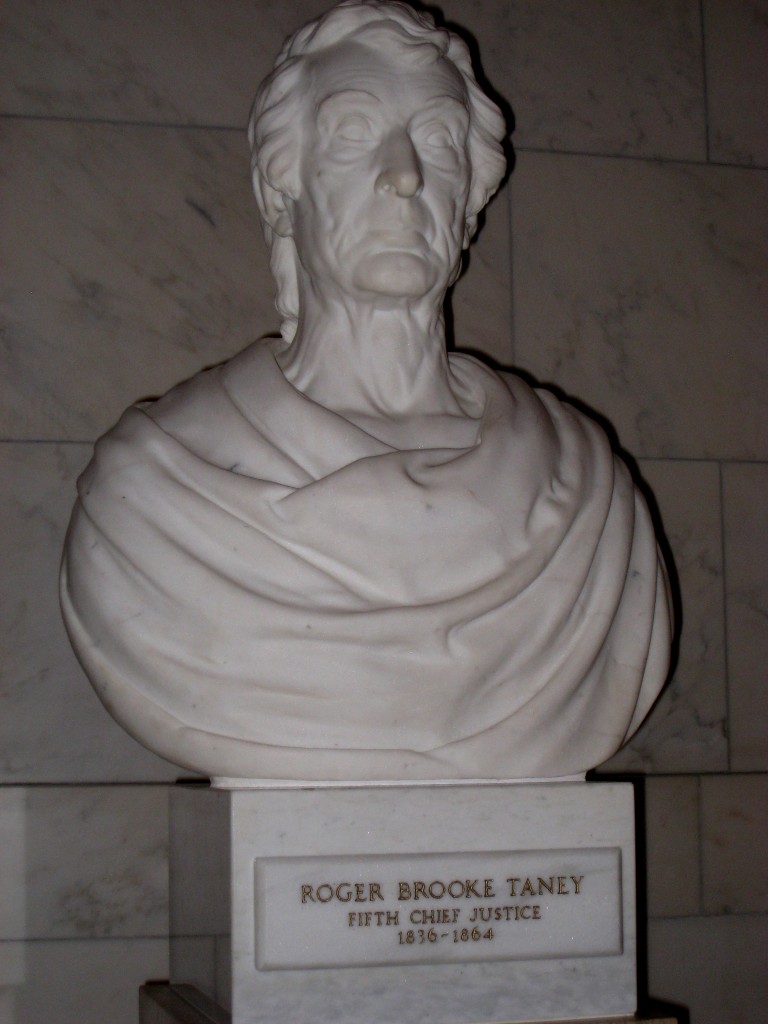

This isn’t the only image of Taney that hangs in shame. There is also a bust of Taney outside Frederick, Maryland City Hall. On Monday, vandals poured an entire bucket of red paint onto Taney’s bust. The vandalism came on the eve of a decision whether to remove the bust because some find it “offensive”:

This isn’t the only image of Taney that hangs in shame. There is also a bust of Taney outside Frederick, Maryland City Hall. On Monday, vandals poured an entire bucket of red paint onto Taney’s bust. The vandalism came on the eve of a decision whether to remove the bust because some find it “offensive”:

Frederick Alderwoman Donna Kuzemchak started the discussion in August, as she considers the statue offensive.

The mayor and aldermen are set to decide Thursday whether it should move to a museum or another historical site.

The discussion fits into a much broader discussion about whether state officials should continue to fly the Confederate Flag. But rather than removing a symbol of the Confederacy, the Frederick government is considering removing the visage of a person–and in this case, the Chief Justice of the United States. At some point, I will publish something that delves into this question in much more depth, but for now, I should stress that this is exact decision may one day face the Supreme Court.

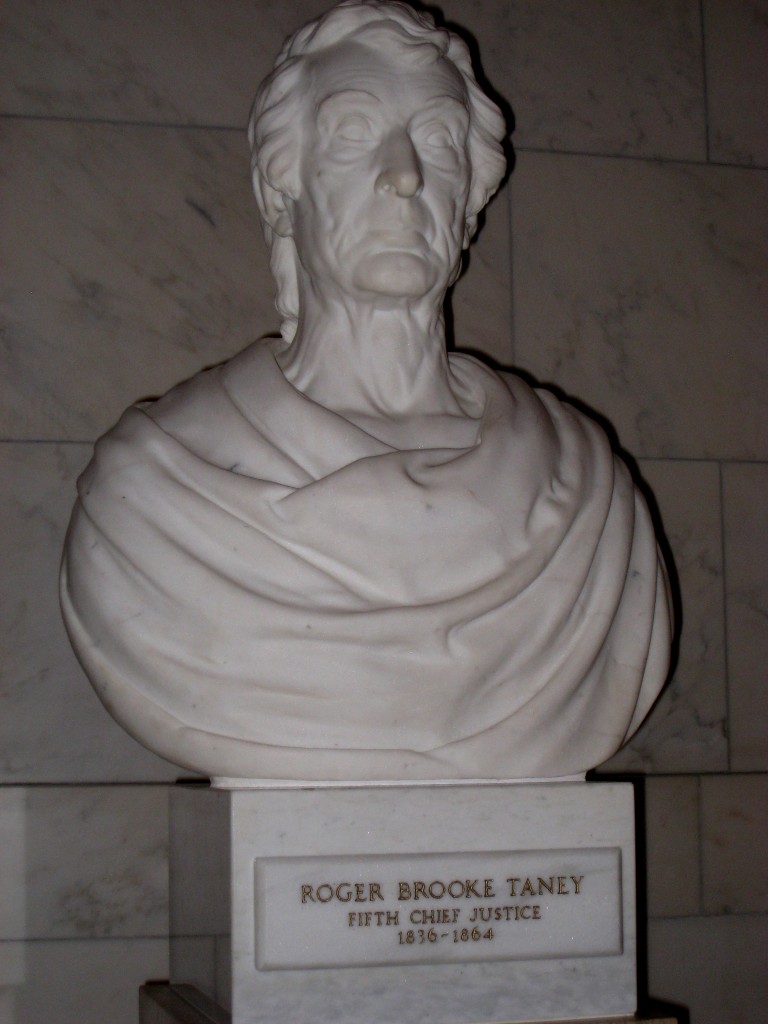

Lining the Great Hall of the Supreme Court are busts of the Chief Justices. Sandwiched between the great visages of John Marshall (the 4th Chief) and Salmon Chase (the 6th Chief) is the blank stare of Roger Brooke of Taney.

Will we one day see a movement to remove the bust of Chief Justice Taney from the Supreme Court?

The debate over memorializing Taney is not new. In the old Supreme Court chamber in the Senate, there is another bust of Taney. But, as the Senate’s archives reveal, there was a debate in 1865 over whether the Taney bust should even be commissioned that involved Lyman Trumbull and Charles Sumer.

The debate over memorializing Taney is not new. In the old Supreme Court chamber in the Senate, there is another bust of Taney. But, as the Senate’s archives reveal, there was a debate in 1865 over whether the Taney bust should even be commissioned that involved Lyman Trumbull and Charles Sumer.

The commissioning of such a bust, however, had previously met with strong opposition in Congress. Several years earlier, in February 1865, a heated debate erupted in the Senate Chamber when Senator Lyman Trumbull of Illinois introduced a bill providing for a bust of Taney for the Supreme Court room. In response, Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts exclaimed: “I object to that; that now an emancipated country should make a bust to the author of the Dred Scott decision.” While Trumbull eulogized the late chief justice, noting that even if Taney had made a wrong decision he was still a great and learned man, Sumner retorted: “Let me tell that Senator that the name of Taney is to be hooted down the page of history. Judgement is beginning now; and an emancipated country will fasten upon him the stigma which he deserves.” Congressional Globe (23 February 1865) 38th Cong., 2d sess., 1012. Following the debate further action on the bill was indefinitely postponed.

There’s nothing new. Ultimately, the bust was commissioned in 1872, alongside a bust for Chief Justice Chase, and was completed in 1877.

Update: Harvard Law School has this description of why it still hangs the portraits of Taney:

Update: Harvard Law School has this description of why it still hangs the portraits of Taney:

The School has two portraits of Roger Taney, fifth Chief Justice of the United States. Because of the subject, they are controversial. Taney was born of a wealthy slave-owning family of tobacco farmers. A private, scholarly man, Taney graduated first in his class from Dickinson College in Pennsylvania in 1795 at the age of eighteen. He received his early legal training in the office of Judge Jeremiah Chase of Annapolis Maryland. On 7 January, 1806, he married Anne Phoebe Charlton Key, only daughter of John Ross Key, and sister of Francis Scott Key, a law student with Taney at Annapolis, who afterwards wrote the Star-Spangled Banner. Upon his father’s death, Taney freed his slaves. As a Maryland litigator in the 1820s, Taney had declared, “Slavery is a blot on our national character, and every real lover of freedom confidently hopes that it will be effectually, though it must be gradually, wiped away.”

The portrait of the younger Taney – which hangs outside the library’s computer lab – was painted by the noted artist Henry Inman during Taney’s tenure as Attorney General. As Andrew Jackson’s attorney general, Taney helped close down the Second Bank of the United States, bringing him in direct conflict with powerful leaders of the Senate, including Daniel Webster and Henry Clay. Despite their opposition, in 1837 Jackson rewarded Taney by naming him Chief Justice of the Supreme Court.

Taney is remembered and respected for such opinions as Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge, Abelman v. Booth, and Ex Parte Merryman. That began to change in 1857, when the Supreme Court faced the case of Dred Scott, a slave who claimed his freedom as a result of being taken by his master to a free state. As the author of the Supreme Court’s majority opinion in Dred Scott v. Sanford, Taney struck down the Missouri Compromise and ruled that the Constitution did not recognize the citizenship of an African American who had been born a slave. This decision sparked bitter opposition from northern politicians and a heated defense from the South and was one of the most important events leading up to the Civil War. This single opinion cast a shadow over Taney’s distinguished legal career and his personal reputation for integrity.

The Law School has many portraits that depict individuals who do not have the most sterling reputations, e.g., Lord Jeffries. Because the school owns and displays a portrait of a given individual is not an endorsement. Rather they are depictions of historical figures who have had some impact on our legal heritage — for good or ill. Taney certainly had an impact on the American legal, social and cultural landscape and the comparison of Harvard’s two portraits is visually interesting.

I could not find a full, color photo of the Leutze painting. Here is the best version I could find.

When most of us visualize Taney, we think of the portrait that hangs at Harvard Law School, which Justice Scalia described in vivid langauge in his

When most of us visualize Taney, we think of the portrait that hangs at Harvard Law School, which Justice Scalia described in vivid langauge in his  This isn’t the only image of Taney that hangs in shame. There is also a bust of Taney outside Frederick, Maryland City Hall. On

This isn’t the only image of Taney that hangs in shame. There is also a bust of Taney outside Frederick, Maryland City Hall. On

The debate over memorializing Taney is not new. In the old Supreme Court chamber in the Senate, there is another bust of Taney. But, as the

The debate over memorializing Taney is not new. In the old Supreme Court chamber in the Senate, there is another bust of Taney. But, as the