For the third term in a row, the Cato Institute has filed its “funny” amicus brief before the Supreme Court. (I am an adjunct scholar at Cato, but have had no role in these briefs). In 2014, Cato’s satirical brief in Susan B. Anthony List v. Driehaus, on behalf of P.J. O’Rourke, used crude humor to explain why even falsehoods are essential to the freedom of speech. In 2015, Cato filed its “funny” brief in Walker v. Texas Division, Sons of Confederate Veterans, on behalf of a “team of expert offenders of good taste,” to urge the Court “to reaffirm that the First Amendment protects the speech of unpopular minorities, even when the proffered justification for censorship is its putative ‘offensiveness.'” In 2016, Cato continued the tradition in Lee v. Tam. In this case, the government denied an Asian-American rock band the trademark “The Slants,” because some bureaucrats at the Patent and Trademark Office found the name “disparaging.”

Cato’s latest brief is a is a tour de force of offensiveness. To prove how ludicrous the government’s position is that it can deny “disparaging” trademarks, the brief went out of its way to disparage everyone and everything. Warning: this document may require trigger warnings on certain college campuses. Indeed, the statement of interest warns, “This case concerns amici because we all say things that some people find offensive or even disparaging—but it’s not the government’s role to make that judgment.”

Here are some of the highlights, or lowlights depending on your perspective.

First, the brief offers a historical perspective of early-efforts at disparaging political speech. Indeed, “Crooked Hillary” and “Lyin’ Ted” are tame by the standards of yesteryear.

Disparaging epithets long ago entered our political vocabulary, encapsulating criticisms more succinctly than any polite term ever could. Schoolchildren today learn that Millard Fillmore ran for president in 1856 as the candidate of the “Know-Nothing” Party; few adults could tell you the party’s “real” name. Yet a hypothetical 1856 PTO would likely have denied registration to a group called “Defeat the Know- Nothings” (disparaging to American Party members), just as the real PTO has denied registration to “Abort the Republicans” (disparaging to Republicans), “Democrats Shouldn’t Breed” (disparaging to Democrats), and a logo consisting of the communist hammer-and-sickle with a slash through it (disparaging to Soviets).

Second, indeed many terms that begin as disparaging are often embraced:

Jesuits, Methodists, Mormons, and Quakers owe their popular names to terms that were originally given to them in a disparaging context, and that have since been reclaimed.4 Without disparaging epithets, our vocabulary would be deprived of such terms as “cavalier,” “yankee,” “impressionist” (Renoir, not Rich Little), and “suffragette.”5 How did a donkey become the Democratic Party symbol? A political opponent labeled Andrew Jackson a “jackass,” so Jack- son put the animal on campaign posters. See Jimmy Stamp, Political Animals: Republican Elephants and Democratic Donkeys, Smithsonian.com (Oct. 23, 2012), http://bit.ly/2gzmfKa. An 1820s PTO might have stopped him.

Third, in particular rock bands–several I had never heard of–have endorsed such offensive terms. The brief spares no details.

Rock bands in particular often pick names because they are “disparaging.” The Slits, the Queers, Queen, Pansy Division, N.W.A. (Niggaz Wit Attitudes), and the Hillbilly Hellcats—there’s that word again—are just a few examples. Other bands, looking to push the envelope both musically and culturally, have chosen names like the Sex Pistols, Dead Kennedys, Butthole Surfers, Rapeman, Snatch and the Poontangs, Pussy Galore, Dying Fetus, and many, many more.

…

“Taking back” disparaging epithets has also been a philosophy of rap and R&B music, both of which use variations of “nigger” in their lyrics and names. N.W.A., one of the most culturally significant groups of the past 30 years, is the most prominent example. Straight Outta Compton (Universal Pictures 2015). They grabbed the slur with pride, announcing to themselves and the world with the brazen opening line, “straight outta Compton, crazy motherfucker named Ice Cube, from the gang called niggaz wit attitudes.” N.W.A., “Straight Outta Compton” on Straight Outta Compton (Ruthless Records 1988).

“A cursory survey just of titles yields Dr. Dre’s ‘The Day the Niggas Took Over,’ A Tribe Called Quest’s ‘Sucka Nigga,’ Jay-Z’s ‘Real Nigger,’ the Geto Boys’ ‘Trigga Happy Nigga,’ DMX’s ‘My Niggas,’ and Cypress Hill’s ‘Killa Hill Nigga.’ In ‘Gangsta’s Paradise,’ meanwhile, Coolio declares, ‘I’m the kind of nigga little homies want to be like on their knees in the night saying prayers in the streetlights.’” Kennedy, supra, at 35–36. N.W.A. received a trademark for its name. That The Slants have been denied one for theirs only underscores the arbitrary and biased nature of the Lan- ham Act’s disparagement clause.

…

Finally, band names are also chosen to convey valuable information about the music the band plays. It should come as no surprise that the Queers are not a Lawrence Welk cover band, the Revolting Cocks are not a string quartet, Dying Fetus does not play jazz standards, and Gay Witch Abortion would never open for Paul Anka. Similarly, The Slants have chosen a name that, through its insouciance, expresses some- thing about their music—and the government’s jejeune label of “disparaging” fails to capture the many levels of communication inherent in that name.

Fourth, some names can be deemed offensive by anyone.

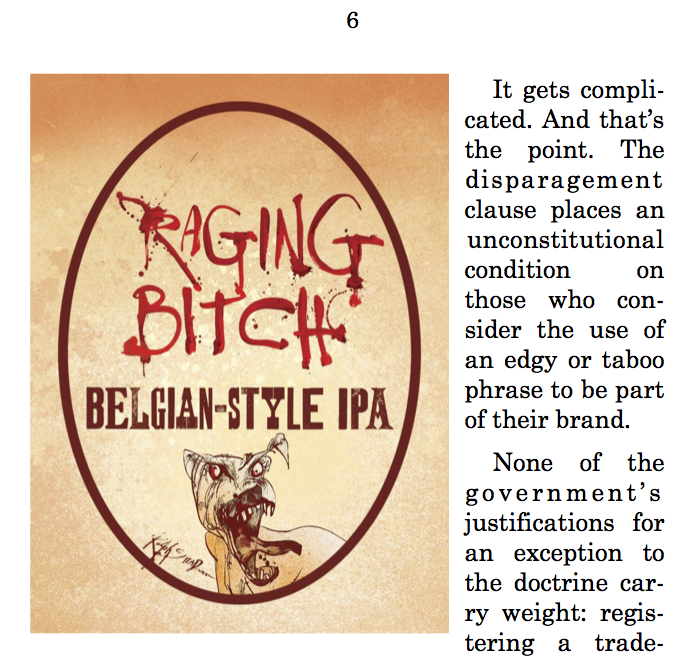

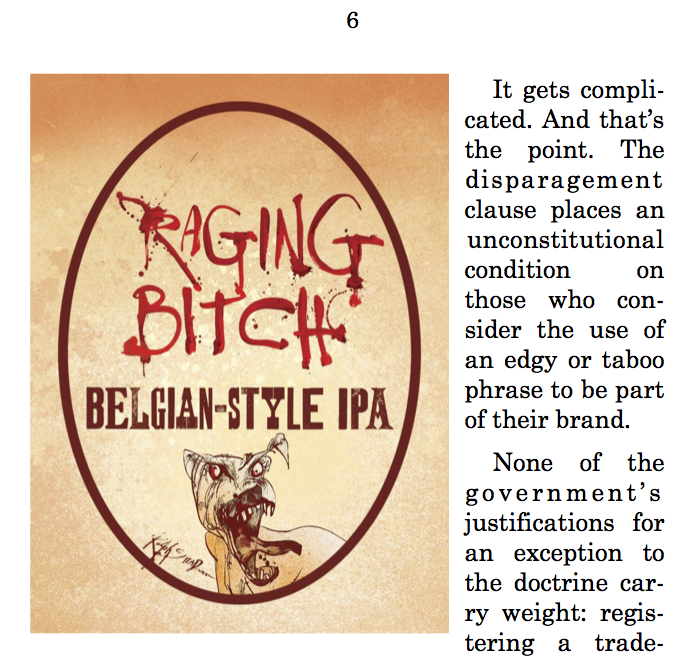

Further, the disparagement clause is unconstitutionally vague. Its application will always be unpredictable, because nearly any brand could be taken as disparaging by some portion of some group. Take, for low-hanging fruit, Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben, the Cleveland Indians’ Chief Wahoo, the women in La Tortilla Factory, or the Keebler Elves. Amicus Flying Dog Brewery has its own history of legal disputes over beer names like “Raging Bitch.” See next page and appendix.

At some expense, Cato submitted its brief in color to include this graphic:

Fifth, getting a bit autobiographical, the brief uses all manners of slurs to refer to amici.

For example, one of this brief’s authors is a cracker (as distinct from a hillbilly) who grew up near Atlanta, but he wrote this sentence, so we can get away with saying that. But he only moved to Atlanta when he was 10 and doesn’t have a southern accent—and modern Atlanta isn’t really part of the South—so maybe we can’t. Another contributor—unnamed be- cause not a member of the bar—is an Italian- American honky who has

wanted to play in a band called the Dagos, which of course would close every set with “That’s Amore” from “Lady and the Tramp.” But, with only his great grandparents having come from Italy, is he dago enough to “take back” the term? And amici’s lead counsel is a Russian- Jewish émigré who’s now a dual U.S.-Canadian citizen. Can he make borscht-belt jokes about Canuck frostbacks even though the first time he went to shul was while clerking in Jackson, Mississippi?

I should note that on the day Ilya took his oath of citizenship at the E. Barrett Prettyman U.S. courthouse, I handed him a filled-out form to renounce his Canadian citizenship. I even offered to walk it over to the Canadian embassy, which was one block away. Ilya still has the form.

Sixth, the brief has a riff on Chris Rock and then-candidate Obama:

In some cases, artists and comedians have harnessed their power to send a critical message. For example, one of the most groundbreaking stand-up routines ever recorded, Chris Rock’s “Niggas vs. Black People,” engaged in cultural commentary that put some African Americans in a negative light—indeed, “disparaged” them. See Niggas vs. Black People, in Chris Rock, Rock This! 17–19 (1997). Many questioned and criticized both Rock’s approach and, specifically, his use of “the N-word.” See, e.g., Eric Bogosian, Chris Rock Has No Time for Your Ignorance, N.Y. Times Magazine, Oct. 5, 1997, http://nyti.ms/2g5SO6c. (“Your audience is made up of whites, many of whom are happy to hear how lazy or stupid blacks are. You’re using the word ‘nigger.’ And some of the white audience is saying, ‘That’s right.’ . . . ‘Nigger’ is a heavy-duty word. You better have a good reason for using it.”). Yet the routine had such cultural resonance that 12 years later it was cited positively by an African- American presidential candidate. See Barack Obama’s Speech on Father’s Day, June 15, 2008, available at http://bit.ly/2ggKS0H. (“Chris Rock had a routine. He said some—too many of our men, they’re proud, they brag about doing things they’re supposed to do. They say ‘Well, I’m not in jail.’ Well you’re not supposed to be in jail!”). The 12-minute riff was undoubtedly an important contribution to an ongoing public debate—and its title and message undoubtedly would have been rejected by the PTO.

Seventh, the brief included riffs from South Park, a show I have been watching since middle school. It’s longevity, and never-ending ability to offend without cancellation, is remarkable.

Indeed, one harm of the government’s approach, which attempts to discern whether a “substantial composite” of a given community has felt disparaged by a mark, is that it will naturally allow certain loud voices in a racial or ethnic community to “speak for” the entire group in determining whether a term has disparaged them. After all, asking a few self-anointed “community leaders” is much easier than ascertaining the sentiments of millions of members of a diverse group.

See South Park, With Apologies to Jesse Jackson (first aired March 7, 2007):

Stan: Hey Token. I just wanted to let you know that every- thing is cool now. My dad apologized to Jesse Jackson.

Token: Oh I see, so I’m supposed to feel all better now.

Stan: Well, yeah.

Token: You just don’t get it, Stan!

Stan: Dude, Jesse Jackson said it’s okay!

Token: Jesse Jackson is not the emperor of black people!

Stan: (confused) He told my dad he was . . .

Eighth, the brief discusses how some words that were totally unoffensive have gained offensive connotations. For example, the word “niggardly.”

There have been similarly intense controversies over the use of the word “niggardly,” which has an entirely innocuous dictionary definition11 but hap- pens to also sound similar to another word of less in- nocuous origins. Use of the word has become so con- troversial that one employee of the D.C. Mayor’s Of- fice lost his job for using it in a public meeting. See Yolanda Woodlee, D.C. Mayor Acted “Hastily,” Will Rehire Aide, Wash. Post, Feb. 4, 1999, http://wapo.st/1j4yg7V. See also Kennedy, supra, at 94–96. What to make of such controversies? Perhaps there are some secret racists who receive a thrill from being able to say “niggardly” out loud and get away with it, like the second-grader who seems to enjoy saying “Hoover Dam” a bit too much. But most, sure- ly, use the word only out of a desire to show that they know their way around a thesaurus. Which definition of “niggardly” would the government use if someone attempted to include the word in a trademark? The dictionary or the dog-whistle? It is hard to know, and that, again, is exactly the problem.

Every year where I assign Youngstown, I brace myself for complaints from uninformed students when they come across this passage in Justice Jackson’s iconic concurring opinion.

However, because the President does not enjoy unmentioned powers does not mean that the mentioned ones should be narrowed by a niggardly construction. Some clauses could be made almost unworkable, as well as immutable, by refusal to indulge some latitude of interpretation for changing times. I have heretofore, and do now, give to the enumerated powers the scope and elasticity afforded by what seem to be reasonable, practical implications instead of the rigidity dictated by a doctrinaire textualism.

I found 62 Supreme Court decisions that use the phrase, most recently in a dissent by Justice Scalia, joined by Justice Thomas, in Cipollone v. Liggett Group (1992):

Applying its niggardly rule of construction, the Court finds (not surprisingly) that none of petitioner’s claims—common-law failure to warn, breach of express warranty, and intentional fraud and misrepresentation—is pre-empted under § 5(b) of the 1965 Act. And save for the failure-to-warn claims, the Court reaches the same result under § 5(b) of the 1969 Act. I think most of that is error. Applying ordinary principles of statutory construction, I believe petitioner’s failure-to-warn claims are pre-empted by the 1965 Act, and all his common-law claims by the 1969 Act.

Three years earlier, Justice Stevens–joined by Justices Marshall, Blackmun, and O’Connor–also used the phrase:

The Court’s niggardly construction to the contrary departs from the enlightened laws that Congress intended to track and defeats Congress’ beneficent purpose

The Court’s two African-American justices joined opinions with the word “niggardly,” without any suggestion to change it to “miserly” or “stingy,” a modification I have adopted in my own usage.

Ninth, in one of the sharper jabs, the brief suggests that the U.S. Reports may also be subject to disparagement claims, because of the Court’s decisions in a few unpopular cases.

The government should be careful if it truly believes that printing a disparaging message on any official publication will forevermore be seen as an imprimatur of endorsement for the respectability of the message conveyed—and that this justifies cleansing such publications of all disparaging sentiments. If so, this Court can only hope, for the sake of its own posterity, that the same principle is not eventually extended to another official publication of the federal government that has printed more than a few disparaging sentiments throughout its history: the United States Reports. See, e.g., Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393 (1856); Bradwell v. Illinois, 83 U.S. 130 (1872); Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896); Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. 200 (1927).

I always warn my students that readings in class will offend them–call it a blanket trigger warning for the semester.

Tenth, the authors of the brief were even willing to attack the Notorious RBG herself!

Indeed, questioning the character of our politicians is such a cherished American tradition that a member of this Court recently engaged in it herself. See Joan Biskupic, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg Calls Trump a “Faker,” He Says She Should Resign, CNN.com, July 11, 2016, http://cnn.it/29zSCUS.

Finally, a few scattered lines that were hapless slaps:

Actual, non-Biden sense of the word “literally.” See, e.g., Alexandra Petri, Literally, Joe Biden, Wash. Post, Sept. 7, 2012, http://wapo.st/2hpA521.

Couldn’t the Redskins controversy be obviated by keeping the name but replacing the logo with a smiling potato head?

“The Slants,” the band played it safe and called themselves “Four Asian-American Men Who Are Very Respectful of Our Diversity as a Nation.” Someone attending a show by such a band might well find it more “destabilizing” to only then discover that the band’s songs contain lyrics referencing the schoolyard taunt “Chinese, Japanese, dirty knees, look at these.” Resp. Cert. Brief 4. Amici, and all others who sometimes find them- selves lumped into a basket of deplorables—now that’s a great band name!—urge the Court to let peo- ple judge for themselves what’s derogatory.

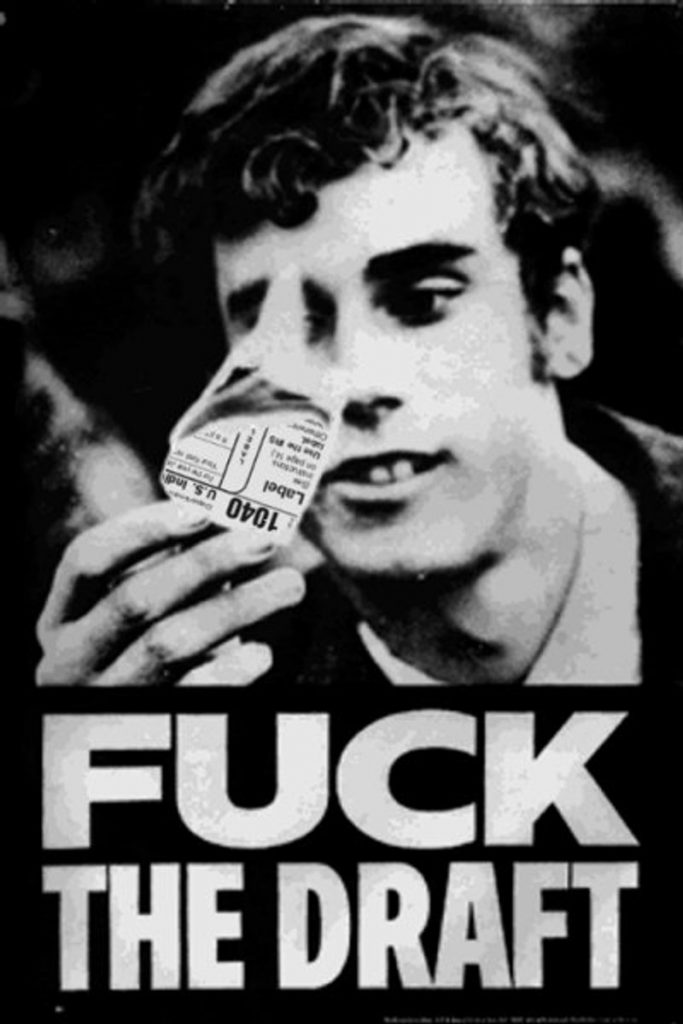

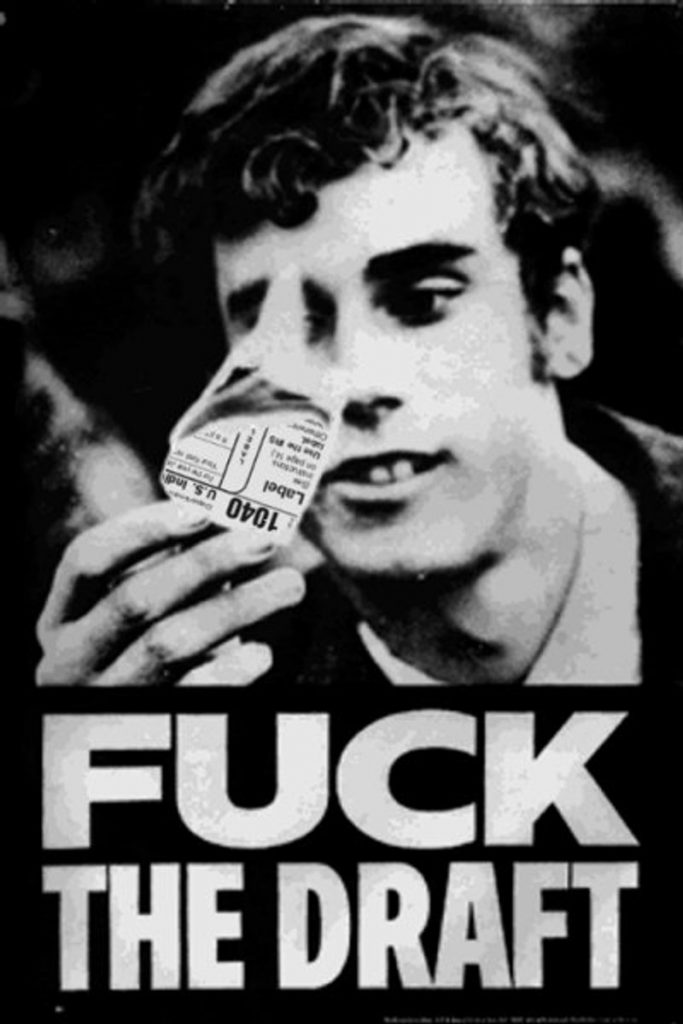

In some of the Supreme Court’s most important First Amendment cases, speech is deliberately designed to be offensive to attract attention to a message: “Fuck the Draft” in Cohen, burning a draft card in O’Brien, or “Thank God For Dead Soldiers” in Snyder. Had these speakers used less disparaging speech–“Darn the Draft,” waving around a draft card, or ” God Hates War”–they simply would not have had the same impact.