This analysis starts with a detour to a classic film: Casablanca. You may recall that people who were trying to flee the Nazis were trying to obtain letters of transit. But having a letter of transit in hand was not enough. The traveller also had to make it past the Nazi checkpoints at the airport. Godwin’s Law aside, this framework is a helpful place to start to understand the relationship between two concepts in immigration law: a visa, and entry.

I wrote in the first part of my series:

A few important points about the text. First, the provision affects “the entry of any aliens.” During debates about the executive order, pundits have conflated two issues: the granting of visas and the decision to allow someone to enter the United States. These are distinct questions. Even if an alien arrives at an airport with a valid visa, he may not be permitted entry to the United States.

By no stretch did I suggest these pundits were “uniformed” (as Ian Samuel implies in a must-read post). Rather, the relationship between these concepts is not entirely clear, due in no small part to the fact that “entry” was used in the pre-1996 law, while “admissibility” is used in the post-1996 law. I used my posts not to make a definitive case one way or the other–not everything I write is advocacy–but to think through this very difficult concept. (Believe it or not, I use my lengthy blog posts not for your readership pleasure, but for my own thought process).

To dive deeper into this topic, let’s consider what the challenged executive order itself does, and does not do. It’s true, as Ian writes, that the executive order uses the phrase “visa” more than two-dozen times. But not a single word anywhere in the order actually directs the State Department to revoke visas. The title of Section 3 does indeed suggest that the Executive Order will suspend visas:

Sec. 3. Suspension of Issuance of Visas and Other Immigration Benefits to Nationals of Countries of Particular Concern.

However, this title is unfortunate because nothing in the order does that. I suppose you can use the title of a provision to give effect to an otherwise ambiguous provision (in Jonathan Mitchell’s class I argued that AEDPA was designed to make the death penalty effective; it has done the exact opposite), but there is nothing ambiguous about what Section 3(a) does. It merely instructs the executive branch to undertake a review to determine what information is needed from a person seeking a visa:

(a) The Secretary of Homeland Security, in consultation with the Secretary of State and the Director of National Intelligence, shall immediately conduct a review to determine the information needed from any country to adjudicate any visa, admission, or other benefit under the INA (adjudications) in order to determine that the individual seeking the benefit is who the individual claims to be and is not a security or public-safety threat.

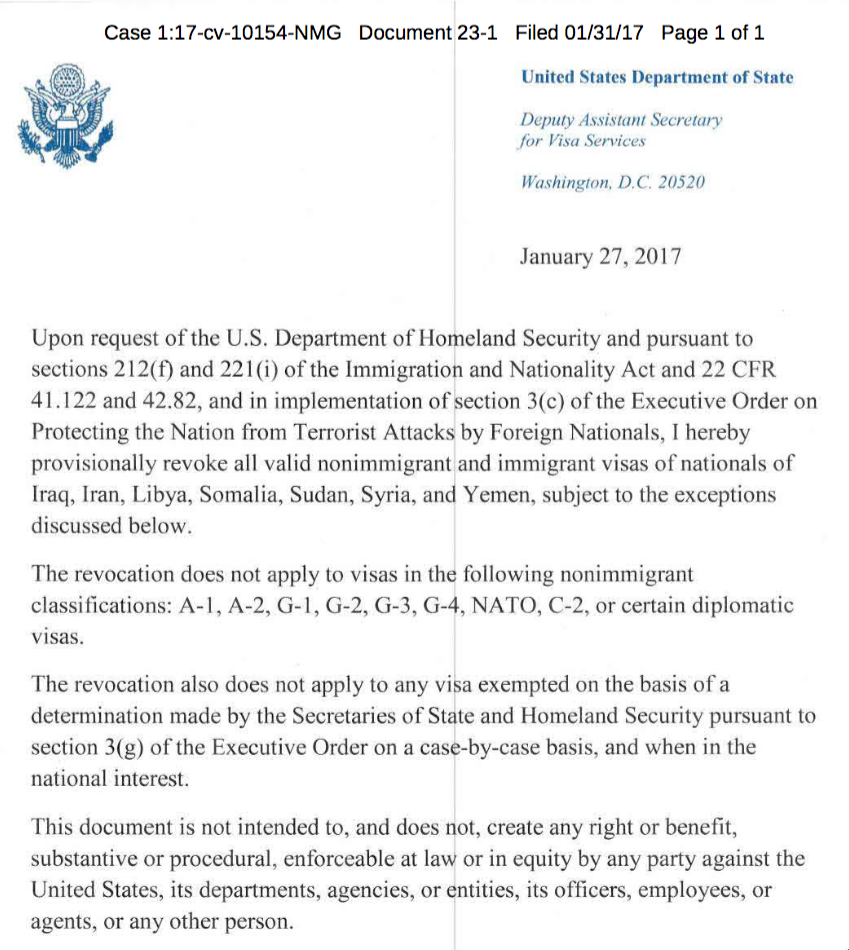

Let me repeat this point: nothing in the executive order compelled the revocation of visas. Why then were thousands of visas revoked? On the same day the executive order was signed, the Deputy Assistant Secretary of State, at the Bureau of Consular Affairs, signed a one page memorandum.

The memorandum cites several sources of authority to “provisionally revoke all valid nonimmigrant and immigrant visas of nationals of Iraq, Iran, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen.”

First, it cites Section 212(f), which everyone from President Trump to Sean Hannity has been reciting of late:

Whenever the President finds that the entry of any aliens or of any class of aliens into the United States would be detrimental to the interests of the United States, he may by proclamation, and for such period as he shall deem necessary, suspend the entry of all aliens or any class of aliens as immigrants or nonimmigrants, or impose on the entry of aliens any restrictions he may deem to be appropriate.

Second, it cites Section 221(i), which governs the Secretary’s authority to revoke a visa:

After the issuance of a visa or other documentation to any alien, the consular officer or the Secretary of State may at any time, in his discretion, revoke such visa or other documentation. Notice of such revocation shall be communicated to the Attorney General, and such revocation shall invalidate the visa or other documentation from the date of issuance: Provided, That carriers or transportation companies, and masters, commanding officers, agents, owners, charterers, or consignees, shall not be penalized under section 273(b) for action taken in reliance on such visas or other documentation, unless they received due notice of such revocation prior to the alien’s embarkation. 3/ There shall be no means of judicial review (including review pursuant to section 2241 of title 28, United States Code, or any other habeas corpus provision, and sections 1361 and 1651 of such title) of a revocation under this subsection, except in the context of a removal proceeding if such revocation provides the sole ground for removal under section 237(a)(1)(B) .

This language is indeed broad. Visas can be revoked “at any time, in his discretion.” Further, there is no “judicial review” of a visa revocation, by habeas corpus, or otherwise. (This provision severely undercuts the due process analysis offered by the 9th Circuit).

22 CFR 41.122 and 22 CFR 42.82 provide further guidance on what it means to provisionally revoke a visas for non-immigrant visas, and immigrant visas, respectively. Critically, in both cases, a provisional revocation–what the State Department memorandum accomplishes–is just that. Provisional, and subject to restoration later. Let us not forget that this policy is in effect for only 90 days, and was not meant to be a permanent policy.

Some have cited 8 U.S.C. § 1152(a)(1) as a prohibition on the revocation of visas based on nationality. Not quite. The provision states:

(A) Except as specifically provided in paragraph (2) and in sections 1101(a)(27), 1151(b)(2)(A)(i), and 1153 of this title, no person shall receive any preference or priority or be discriminated against in the issuance of an immigrant visa because of the person’s race, sex, nationality, place of birth, or place of residence.

(B) Nothing in this paragraph shall be construed to limit the authority of the Secretary of State to determine the procedures for the processing of immigrant visa applications or the locations where such applications will be processed.

This provision only applies to the “issuance” of visas, not revocations. In other words, nothing in the statute prohibits the revocation of already-extent visas. There is no statutory prohibition on revoking visas based on a person’s nationality. This policy is, as far as I can tell, completely consistent with the statutory authority given to the Secretary by Congress.

Indeed, this analysis reconciles with one of Ian’s more memorable arguments: why would the Executive Order allow people with visas to travel to the United States, but not allow them to enter, and thus get stuck at Terminal 4. Under this order, they would not be able to. By provisionally revoking visas from nationals of those seven countries, the aliens would not be able to get on the plane in the first place. Thus, they would never get stuck in Terminal 4.

8 U.S.C. § 1152(a)(1) does, however, implicate changes made by the State Department with respect to issuing new visas. I’ll pause for a moment to note that Congress put no nationality-based restrictions on the revocation of visas; only on the issuance of visas. This is significant. The notion of excluding classes of people–even those already vetted–in times of crisis seems an inherent attribute of sovereignty. To return to an example I’ve used before, if U.S. relations with a certain country deteriorate, short of making a finding of inadmissibility for each national with a valid visa on a case-by-case basis, it would be far more convenient to revoke them as a class. This is also a better option than permitting them to travel to the United States, but deny them entry. (Do we establish a permanent detention center at the airport?). Ian uses, with great flourish, the example of “No Irish shall be admitted.” I think a better example would be a statement in 1942 that “No Germans shall be admitted,” even if they had a previously issued immigrant visa. These are provisions that are seldom invoked, but exist specifically for tough times. (To reiterate a point I made elsewhere, even in the absence of this statute, I think the President would have the Article II powers to accomplish just this; the statute is a reaffirmation of that inherent authority, which brings us within Jackson’s first Tier).

Back to “issuance.” As a threshold matter, Section 1152(a)(1) only applies to immigrant visas; not non-immigrant visas. Therefore, there is no statutory objection to the government denying non-immigrant visas based on nationality. (Yet another reason why the TRO was extremely overbroad). Therefore, my analysis will focus on a policy that restricts immigrant visas to aliens based on their nationality.

A State Department cable, released shortly after the executive order, sent this guidance to consular offices concerning immigrant visas:

(U) Immigrant Visas

7. (SBU) The National Visa Center (NVC) will attempt to contact all applicants from the restricted countries with scheduled immigrant visa (IV) appointments for February in order to cancel their appointments. In addition, NVC will not schedule nationals of these seven countries for March or April immigrant visa appointments. For diversity visa (DV) applicants scheduled for interviews between February 5 and March 31, the Kentucky Consular Center (KCC) will notify applicants to check Entrant Status Check where they will see a message notifying them that their appointments will be rescheduled. NVC and KCC are unable to identify IV and DV applicants who may hold dual nationality with a restricted country but who are interviewing under the nationality of a non-restricted country for purposes of cancelling or postponing appointment scheduling. For applicants whom KCC and NVC are unable to contact, or otherwise unable to cancel or postpone, post should attempt to identify them at intake before their interview and notify them that their interviews must be rescheduled. Posts will need to cancel remaining January appointments for affected applicants.

Does this look like a policy that, in the words of 8 U.S.C. § 1152(a)(1)(A), discriminates on the basis of a person’s “nationality” with respect to the “issuance of an immigrant visa”? It does. (Query for a moment whether enjoining the executive order, rather than the specific State Department cable which imposes the nationality-based visa policy, was the proper remedy; that is, could this cable exist even if the executive order was enjoined?).

However, subparagraph (A) is not the only relevant provision. Subparagraph (B) states:

(B) Nothing in this paragraph shall be construed to limit the authority of the Secretary of State to determine the procedures for the processing of immigrant visa applications or the locations where such applications will be processed.

Let’s go back to Section 3(a) of the Executive Order:

The Secretary of Homeland Security, in consultation with the Secretary of State and the Director of National Intelligence, shall immediately conduct a review to determine the information needed from any country to adjudicate any visa, admission, or other benefit under the INA (adjudications) in order to determine that the individual seeking the benefit is who the individual claims to be and is not a security or public-safety threat.

Could it be that under the authority of Subparagraph (B), the Secretary can “determine the procedure” for issuing visas to nationals of those seven countries, “notwithstanding” the nondiscrimination provision in Subparagraph (A)? The text certainly permits that construction. But wouldn’t subparagraph (B) render subparagraph (A) a nullity, if it can be carved out of existence? Not necessarily. Subparagraph (A) establishes the general rule of nondiscrimination, but subparagraph (B) ensures that the Secretary has a degree of latitude to craft procedures, “notwithstanding” anything in the previous sentence. This is especially important with respect to concerns about national security.

If we continue reading the remainder of 8 U.S.C. § 1152, we will see how much the government can treat nationals of one country different than national of another country, “notwithstanding” subparagraph (A):

(2)Per country levels for family-sponsored and employment-based immigrants

Subject to paragraphs (3), (4), and (5), the total number of immigrant visas made available to natives of any single foreign state or dependent area under subsections (a) and (b) of section 1153 of this title in any fiscal year may not exceed 7 percent (in the case of a single foreign state) or 2 percent (in the case of a dependent area) of the total number of such visas made available under such subsections in that fiscal year.

And what if a national of a disfavored nation disagrees with those vetting procedures that implicates nationality, imposed under subparagraph (B)? Too bad. As I wrote in the last post–citing a 1997 D.C. Circuit decision by Judge Sentelle, and joined by Judged Randolph and Chief Judge Edwards–these provisions are not subject to judicial review.

First, the broad language of the statute suggests that the State Department policy is unreviewable. Congress has determined that “[e]very alien applying for an immigrant visa and for alien registration shall make application therefor in such form and manner and at such place as shall be by regulations prescribed.” 8 U.S.C. § 1202(a) (emphasis added). This section grants to the Secretary discretion to prescribe the place at which aliens apply for immigrant visas without providing substantive standards against which the Secretary’s determination could be measured. Plaintiffs argue that there is a standard against which to measure the Secretary’s decision in the prohibition against nationality discrimination contained in 8 U.S.C. § 1152. That argument is untenable after the adoption of section 633. That enactment made clear that the prohibition against nationality discrimination does not apply to decisions of where to process visa applications. These determinations are left entirely to the discretion of the Secretary of State

In addition, the nature of the administrative action counsels against review of plaintiffs’ claim. By way of comparison, the Supreme Court has held that the Food and Drug Administration’s refusal to take enforcement action is unreviewable because it “involves a complicated balancing of a number of factors which are peculiarly within [the agency’s] expertise.” Heckler, 470 U.S. at 831, 105 S.Ct. at 1655–56. Similarly, in this case the agency is entrusted by a broadly worded statute with balancing complex concerns involving security and diplomacy, State Department resources and the relative demand for visa applications. However, in this case the argument for executive branch discretion is even stronger. By long-standing tradition, courts have been wary of second-guessing executive branch decision involving complicated foreign policy matters. See, e.g, Williams v. Suffolk Ins. Co., 38 U.S. 415, 420, 13 Pet. 415, 10 L.Ed. 226 (1839); Garcia v. Lee, 37 U.S. 511, 517–18, 520–21, 12 Pet. 511, 9 L.Ed. 1176 (1838); Foster v. Neilson, 27 U.S. 253, 307–310, 2 Pet. 253, 7 L.Ed. 415 (1829). As we noted in another context, “where the President acted under a congressional grant of discretion as broadly worded as any we are likely to see, and where the exercise of that discretion occurs in the area of foreign affairs, we cannot disturb his decision simply because some might find it unwise or because it differs from the policies pursued by previous administrations.” DKT Memorial Fund Ltd. v. Agency for Int’l Dev., 887 F.2d 275, 282 (D.C.Cir.1989). In light of the lack of guidance provided by the statute and the complicated factors involved in consular venue determinations, we hold that plaintiffs’ claims under both the statute and the APA are unreviewable because there is “no law to apply.”

Legal Assistance for Vietnamese Asylum Seekers v. Dep’t of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs, 104 F.3d 1349, 1353 (D.C. Cir. 1997) (Sentelle, Edwards, and Randolph).

One parting note about this case, titled Legal Assistance for Vietnamese Asylum Seekers v. Dep’t of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs: Ian cites an earlier instance of the case from 1995, that was vacated by the Supreme Court after the enactment of the 1996 immigration law. (Westlaw shows a red flag for the case he referenced).

Here is the per curiam opinion from the Court:

The judgment is vacated and the case is remanded to the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit for further consideration in light of Section 633 of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRA) (enacted as Division C of the Department of Defense Appropriations Act, 1997, Pub. L. No. 104-208, 110 Stat. 3009 (1996)).

As I noted at the outset, this material is very complicated and is subject to decades of caselaw under both regimes. I don’t pretend this issue is clear-cut. But the court of appeals grossly erred by leaping over the issue, which could have potentially resolved much of the case.