Class 5 – 1/26/17

The Executive Power II- Foreign Affairs and War

- Dames & Moore v. Regan (554 – 558)

- Hirabayashi v. United States (558 – 567)

- Korematsu v. United States (568 – 576)

- Ex Part Endo (577 – 581)

- ISIS (Reading to be posted)

The lecture notes are here.

The lecture notes are here.

The Executive Power II- Foreign Affairs and War

- Inherent Executive Powers (308).

- Executive Powers for Foreign Affairs (383-385).

- Curtiss-Wright (385-390).

- Dames & Moore v. Regan (392-399).

- The War Power (411-413).

- ISIS

- Practice and Precedent (415-416).

- Prisoners of War and Civilian Detention (439-440).

- Korematsu v. United States (454-468)

Dames & Moore v. Regan

This is Donald T. Regan, who was the secretary of the treasury in Dames & Moore v. Regan.

This is the logo for the Dames & Moore Group Company.

Justice Rehnquist wrote Dames & Moore v. Regan in a short span of 8 days. There are several remarkable aspects of this opinion. First, Rehnquist cites as the definitive statement of executive power Justice Jackson’s concurring opinion Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer.

Justice Rehnquist wrote Dames & Moore v. Regan in a short span of 8 days. There are several remarkable aspects of this opinion. First, Rehnquist cites as the definitive statement of executive power Justice Jackson’s concurring opinion Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer.

Of course, Rehnquist clerked for Jackson that term. As Judge Bybee noted in this article:

Of course, Rehnquist clerked for Jackson that term. As Judge Bybee noted in this article:

Rehnquist’s first professional brush with the separation of powers came soon after the start of his legal career as a junior law clerk to Justice Robert Jackson. It was an auspicious start. Rehnquist began his clerkship in February 1952, just months prior to the famous Youngstown separation of powers litigation at the Supreme Court . . . . On May 16, 1952, the Court voted 6-3 in conference to reject Truman’s claim of authority to seize the steel mills.15 As Justice Jackson described the vote to his then-law clerks William Rehnquist and C. George Niebank, Jr., “Well boys, the President got licked.’

Yet, Youngstown was written by Jackson himself, with little involvement by his clerks. In fact Rehnquist and his co-clerks suggested resolving the case on non-separation of powers grounds.

To begin, Jackson’s law clerks had very little hand in drafting his opinions generally and little role in preparing the Youngstown concurrence specifically. 30 Thus, the Youngstown concurrence represented Jackson’s, not Rehnquist’s, work product. In fact, archival materials indicate law clerk Rehnquist suggested alternate non-separation of powers grounds on which Youngstown might have been resolved. In an apparently unsolicited memorandum to Justice Jackson, William Rehnquist and his co-clerk proposed they undertake additional research for Youngstown. Interestingly, all the issues proposed non-separation of powers grounds for resolving the appeal–e.g., by balancing equities on the preliminary injunction, etc.31 To be sure, the 1952 clerk memorandum, standing by itself, would be a thin reed to support a claim that Rehnquist had doubts about resolving the separation of powers question in Youngstown against the President. It might merely suggest Rehnquist favored the parsimonious adjudication of constitutional cases by resort to avoidance. The memorandum, however, does not stand by itself. In his book The Supreme Court, Rehnquist, without mentioning his prior memorandum, expressed doubts about how Youngstown was resolved. Noting that the separation of powers issue was not well settled, but in his view “more or less up for grabs,” he believed Youngstown might have been resolved on the balancing of equities and that the law on those issues favored the executive.32

When pressed to write Dames & Moore v. Regan in a short span of 8 days, Rehnquist elevated Jackson’s concurrence to the effect holding of the case (and modified it along the way). And guess who was clerking for Justice Rehnquist in 1981 when Dames & Moore was decided.

A young pup names John G. Roberts (first from the right), who would go on to replace his boss as the Chief Justice of the United States.

On the last day of the term in 1981, for instance, Justice Rehnquist wrote for a unanimous court to say that Presidents Carter and Reagan had the legal authority to nullify court orders and suspend private lawsuits as part of the agreement with Iran that ended the hostage crisis there. The decision, Dames & Moore v. Regan, took an exceptionally deferential view of executive power.

Judge Roberts cited the decision last year in an opinion accepting the Bush administration’s position that it could block claims against Iraq from American soldiers who had been tortured there during the Persian Gulf war.

Korematsu v. United States

This is a young Fred Korematsu.

This is Fred Korematsu later in life.

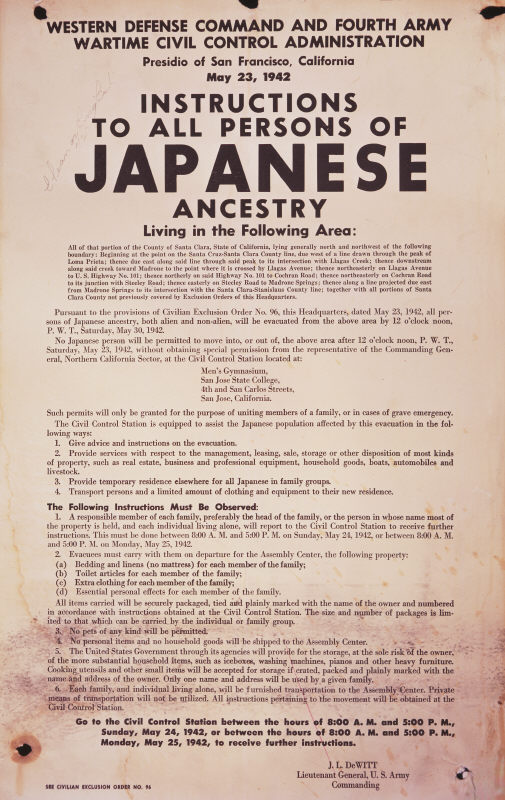

This is an announcement the United States Government posted, ordering “all persons of Japanese ancestry” to be rounded up.

It says:

Pursuant to the provisions of Civilian Exclusion Order No. 33, this Headquarters, dated May 3, 1942, all per- sons of Japanese ancestry, both alien and non-alien, will be evacuated from the above area by 12 o’clock noon, P. W . T., Saturday, May 9, 1942.

No Japanese person living in the above area will be permitted to change residence after 12 o’clock noon, P.W.T., Sunday, May 3, 1942, without obtaining special permission from the representative of the Commanding General

The Civil Control Station is equipped to assist the Japanese Population affected by this evacuation in the following ways:

- Give advice and instructions on the evacuation.

- Provide services with respect to the management, leasing, sale, storage or other disposition of most kinds of

property, such as real estate, business and professional equipment, household goods, boats, automobiles and livestock.

- Provide temporary residence elsewhere for all Japanese in family groups.

- Transport persons and a limited amount of clothing and equipment to their new residence.

Here is a piece of U.S. Government propaganda explaining the “relocation” and do the “job as a democracy should. With consideration.”

Fast-forward to 12:30 when the narrator says there are no constitutional problems with the internment.

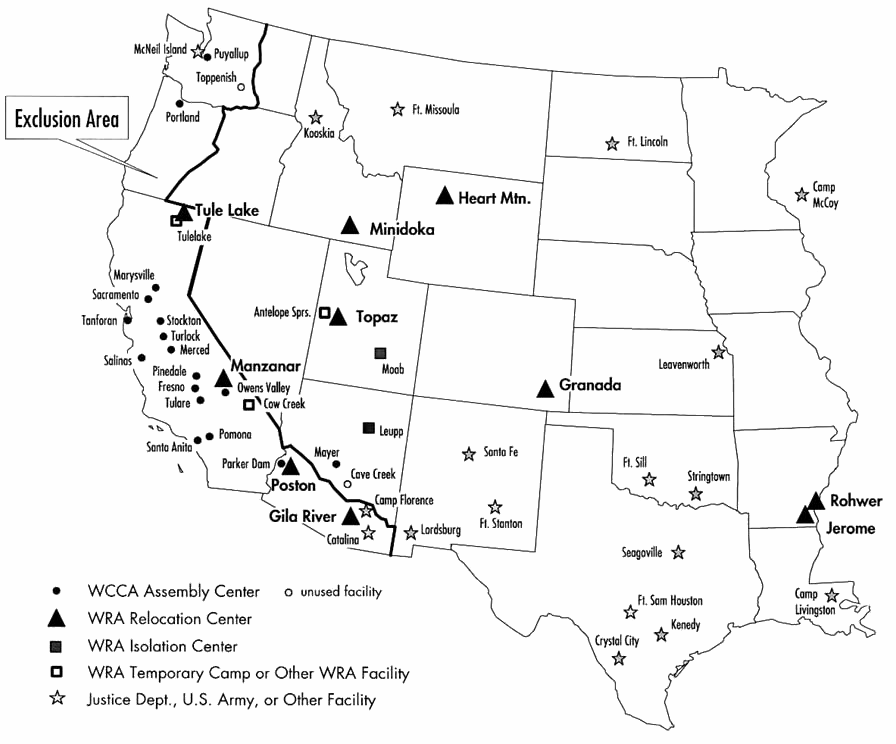

Here is a map of the “relocation centers” and camps.

The San Francisco Examiner announces the “Ouster of all Japs in California near.”

The San Francisco Examiner announces the “Ouster of all Japs in California near.”

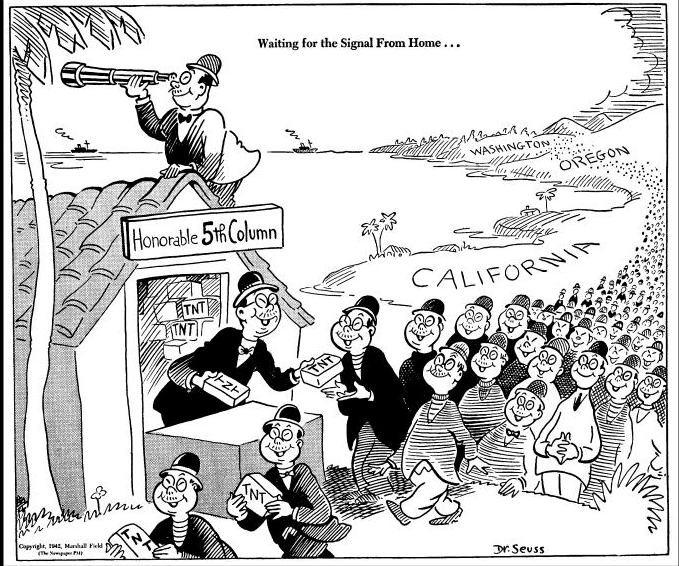

To give you a sense of the propaganda, here is a cartoon drawn by Dr. Seuss (Theodor Giesel):

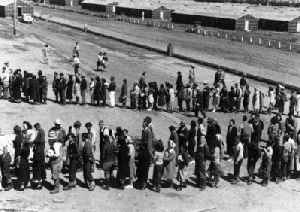

‘This is a so-called “temporary camp” or “assembly center” that were set up in public places, like fairgrounds, before the Japanese-Americans could be transported to the “Detention centers” dubbed “Relocation Centers.”

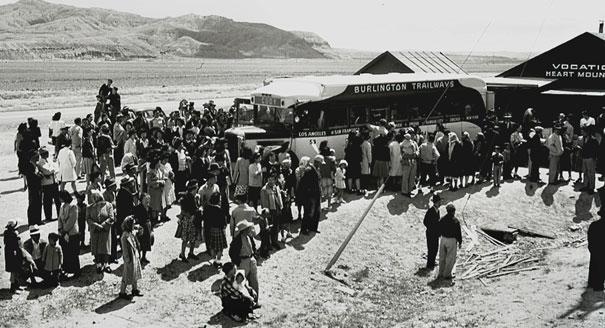

This is the Topaz Internment Center in Utah, where Fred Korematsu was sent.

Here are Americans locked up in internment camps.

Another photographed of interned Americans.

Here are Americans being rounded up on busses to the middle of the Utah desert.

Here is Eleanor Roosevelt at an internment camp.

This great picture contains a meeting of Fred Korematsu, Minoru Yasui, and Gordon Hirabayashi, who also had companion cases before the Supreme Court.

And here is Fred Korematsu posing with Rosa Parks.

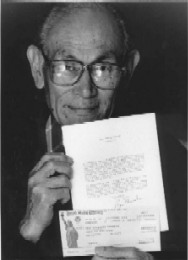

In 1990, Korematsu received a redress letter and a reparations check for his internment.

President Clinton would Korematsu the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1998.

Korematsu passed away in 2005.

The lead plaintiff in a related case was Gordon Hirabayashi. In Hirabayashi, the Court upheld curfews directed towards Japanese Americans because the nation was at war with Japan.

And this is Mutsuye Endo.