On Thursday, I blogged about the dangerous precedents set by the University of Oregon’s decision that it could punish a professor for wearing black face at a Halloween party. In this post, I will discuss how the University’s report completely ignores precedents that are directly on point. This decision is not only dangerous, but is wrong.

Let’s start with Berger v. Battaglia, 779 F.2d 992 (4th Cir. 1985). In this case, an officer with the Baltimore Police Department performed musical routines in blackface while off duty.

In none of his performances did Berger identify himself as a police officer; offer any comment on Department policies or operations; make any reference to any other member of the Department; nor claim to be speaking for or in any way representing the Department. Although various media, in commenting on or describing his performance, referred to him as “the singing cop,” that designation was, so far as the record reveals, theirs, not Berger’s. In his performances Berger’s only purpose was to provide entertainment for willing listeners. He urged no conduct, incited no activity, made no derogatory or inflammatory remarks, advocated no lawlessness and sought no confrontation.

As you could imagine, many found his performances offensive. The NAACP and others organized a picket line, and tried to stop Berger’s performances–potentially by “physical force.”

On February 9 Dr. Burns and approximately 30 persons associated with the N.A.A.C.P. set up a picket line outside the Hilton to protest the continuation of the engagement. They were joined by Bobby Cheeks and eight members of the Baltimore Welfare Rights Organization, of which Cheeks was executive director. The pickets marched in a circle on the sidewalk, carrying placards stating their objections to the show.

As the time for Berger’s performance drew near, some of the pickets or demonstrators entered the hotel and the nightclub itself, with the intention of preventing the performance. In keeping with the policy of the N.A.A.C.P., it was not then the intention of Dr. Burns and his group to resort to violence or other unlawful activity to achieve their goal. On the other hand, Mr. Cheeks and his followers were then prepared, according to Cheeks’ testimony, to go onto the stage and stop the show, by physical force if necessary.

Because of the threat of violence, additional police forces were called in for backup, leaving other posts “unmanned.” The hotel ultimately “cancelled the show.” After the cancellation, the police department received many complaints from the community:

Following the events of February 9, the police department received a number of complaints from black citizens, including Dr. Burns and Mrs. Enolia McMillan, executive director of the Baltimore branch of the N.A.A.C.P., objecting vehemently to a police officer’s being permitted, as they saw it, to offer a public insult to members of their race. These complaints were a matter of serious concern to the Department, which had been engaged since the mid-to late-1960’s in what Deputy Commissioner Bishop L. Robinson described as a “comprehensive, integrated community approach” to improving its previously strained relations with the black citizens of Baltimore. The Department feared that its community relations efforts would be undermined by widespread outrage over Berger’s performances.

The Department asked Berger to “cease all public performances, in any capacity, while on light-duty status.” Berger’s attorney told him that the order was “unconstitutional,” so he refused. The Department once again ordered him to “cease appearing in public wearing blackface on pain of being found in violation of the Department’s rule prohibiting activity on the part of a member of the Department ‘that tends to reflect discredit upon himself or upon the Department.'” Berger refused, and was later reassigned to a desk job, and “stripped of his police powers.”

Berger filed an action under Section 1983, alleging a violation of his First Amendment rights. Applying Pickering, the district court concluded that the speech was on “a matter of public concern,” but “ascribed overpowering weight to the Department’s interests in avoiding future diversions of its resources to cope with threatened disruptions by offended members of Baltimore’s black community of comparable Berger performances, and in maintaining the Department’s hard-earned good relations with that formerly hostile black community.” It ruled for the Department. On appeal, the Fourth Circuit reversed.

The court first concludes that the “artistic expression” was on a matter of public concern–regardless of whether it is “political” in nature:

We think, instead, that in assessing its value for Pickering balancing purposes, this type of off-duty public employee speech has to be accorded the same weight in absolute terms that would be accorded comparable artistic expression by citizens who do not work for the state. And that value, traditionally, has been accorded a great deal of weight, certainly not far below the value accorded political and social commentary and debate . . . . We therefore accord Berger’s speech the value, in absolute terms, that it would be accorded in any citizen, undiminished by the fact here of his state employment.

The Fourth Circuit further rejected the district court’s conclusion about the Department’s interest outweighing the employee’s free speech rights. The court notes that Pickering is not really a perfect fit, because the speech does not criticize or question the employer, and does not cause a “direct disruption of employment relationships” that would stem from “insubordination or disloyalty.” Berger’s speech was in no sense critical of the government:

Instead the speech here was a form of artistic expression wholly unrelated in content to the public employer or its operations, and the threat it assertedly posed to employer interests was not internal disruption by the speech itself, but external disruption by third persons reacting to the speech.

Further, there was no “direct” or “internal disruption” from the speech.

Here not only was the perceived threat of disruption only to external operations and relationships, it was caused not by the speech itself but by threatened reaction to it by offended segments of the public. Short of direct incitements to violence by the very content of public employee speech (in which case the speech presumably would not be within general first amendment protection), we think this sort of threatened disruption by others reacting to public employee speech simply may not be allowed to serve as justification for public employer disciplinary action directed at that speech.

This is a perfect encapsulation of where the University of Oregon’s report went awry. Professor Shurtz’s costume did not cause any sort of disruption, but the punishment was justified by the “threatened reaction” to her costume “by offended segments of the public.” At bottom, the dispute arose only because of the so-called hecklers-veto. The Fourth Circuit addressed this point:

Historically, one of the most persistent and insidious threats to first amendment rights has been that posed by the “heckler’s veto,” imposed by the successful importuning of government to curtail “offensive” speech at peril of suffering disruptions of public order.

See Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U.S. 229, 83 S.Ct. 680, 9 L.Ed.2d 697 (1963);

Terminiello v. City of Chicago, 337 U.S. 1, 69 S.Ct. 894, 93 L.Ed. 1131 (1949). Government’s instinctive and understandable impulse to buy its peace—to avoid all risks of public disorder by chilling speech assertedly or demonstrably offensive to some elements of the public—is a recurring theme in first amendment litigation.

See, e.g., Lehman v. City of Shaker Heights, 418 U.S. 298, 94 S.Ct. 2714, 41 L.Ed.2d 770 (1974);

Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15, 91 S.Ct. 1780, 29 L.Ed.2d 284 (1971);

Rowan v. Post Office Department, 397 U.S. 728, 90 S.Ct. 1484, 25 L.Ed.2d 736 (1970);

Terminiello v. City of Chicago, 337 U.S. 1, 69 S.Ct. 894, 93 L.Ed. 1131 (1949);

Collin v. Smith, 578 F.2d 1197 (7th Cir.1978).

Though this “veto” has probably been most frequently exercised through legislation responsive to majority sensibilities, the same assault on first amendment values of course occurs when, as here, it is exercised by executive action responsive to the sensibilities of a minority.

There is a lot packed into the final sentence, written by a court situated in the former capital of the Confederacy. Traditionally, the heckler’s veto was used to shut down the constitutional rights of minorities. To use an extreme example, in

Cooper v. Aaron, Arkansas contended that Central High School must remain segregated to prevent rioting mobs from threatening African-American students. The district court actually accepted that rationale, but the Supreme Court rejected it: the Constitution cannot be shut down by hecklers. At some point in American history, this principle was well understood by the left. Unfortunately, recent caselaw has given more power to the heckler’s veto, including a

decision from the Ninth Circuit permitting the punishment of a student for wearing an American Flag shirt on Cinco de May, because it offended Mexican students.

The Fourth Circuit ruled that Berger could only be asked, not ordered, to stop performing. The Department has a duty to uphold not only “public order,” but also the “First Amendment”–an argument lost in Eugene:

As indicated, the special dilemma presented for the Police Department here can only excite judicial sympathy. One may well feel—as undoubtedly did the Department—that a little forbearance on the part of Berger, given the special circumstances of his public employment and the hard-earned and presumably still tenuous trust of the black community, would be in order. One may also wonder—as undoubtedly did the Department—whether the outrage being represented to it as that of the “black community” was truly that widely shared and whether a better and more effective response might have been continued public non-violent demonstrations of contempt and outrage by those sufficiently offended.

Nevertheless, however real the dilemma, we think and hold that the Department—after all an agency of the state charged with enforcing the first amendment as well as with maintaining public order—could not respond as it did consistently with the first amendment, once Berger had declined to forbear and stood on his constitutional rights. Those rights of course exist in the unforbearing as well as the forbearing and have in fact undoubtedly been hammered out largely in behalf of the temperamentally unforbearing who are fortunate enough to live in a society that protects their right immediately to “stand on their rights.”

What should the Department have done? Here is sage advice for the University of Oregon from the Fourth Circuit:

An appropriate Department response, perhaps the only one, wholly consistent with the first amendment, would have been instead to say to those offended by Berger’s speech that their right to protest that speech by all peaceable means would be as stringently safeguarded by the Department as would be Berger’s right to engage in it. We have no illusions that this would have been a satisfactory response, nor that it *1002 may not have led to some of the very disruption of operations and resources that the Department feared. But it would not only have been the most sound response constitutionally, it would have been an eminently practical one for any of those offended by Berger’s speech who were at least willing to consider the wider implications of the principle for which they at least implicitly contended: that offensive speech may properly be curbed by exerting this form of leverage upon public employers. But this is a device as readily seized upon by one group in society as another, and is one more readily available in most times to majority than to minority groups.

Would this not have been a far more productive use of resources, than launching an inquisition to punish a tenured professor?

The opinion closes with a fitting vignette from the Fifth Circuit:

There are of course many illustrations of this, but a particularly apt one for this purpose is that considered by the Fifth Circuit in Battle v. Mulholland, 439 F.2d 321 (5th Cir.1971). There a black police officer in a small Mississippi town had been discharged by the town officials because of the town fathers’ concern, prompted by complaints, and probably justified, that his conduct would exacerbate an already tense racial situation in the town. Noting that this “type of restrictive response, based on theoretical reactions by others” to conduct protected by the first amendment had “long been condemned,” the court held the discharge constitutionally impermissible. We think that the principle applied there is precisely that one applicable here, though figuratively, the shoe here is on the other foot.

Imagine that. Oh, and the ACLU of Maryland represented Mr. Berger. Where is the ACLU today on this issue?

The Ninth Circuit has not addressed Berger directly–though it did address a similar case from the Tenth Circuit (Flanagan) in the context of a police officer’s extra-curricular porno web site. But a concurring opinion by Judge Canby favorably cited Berger:

The majority opinion states that to the extent that Flanagan and Berger “minimize the potential for an actual effect on the efficiency and efficacy of police department functions arising from public perceptions of the inappropriate activities of police officers, they are severely undermined by Roe.” Supra, p. 929 n. 7. The rationale of Flanagan and Berger, however, was not that disruption was minimal, but that as part of the heckler’s veto it could not support discipline of the employee. . . . In my view, the rationale of Flanagan and Berger is not only sound, but constitutionally required. We should apply those principles and hold that Dible’s expressive website conduct was an unconstitutional ground for his discharge.

Dible v. City of Chandler, 515 F.3d 918, 934 (9th Cir. 2008)

The University of Oregon’s report makes no mention of any of these cases. For a moment, try to compare the state’s interest in Berger )preventing actual violent riots), with the University of Oregon’s interest (preventing a “racially hostile environment” and “sense of anxiety and mistrust” among students). The report’s Pickering analysis is pathetically wrong. In a different time, these dynamics would have been viewed as part of a robust academic environment, where difficult questions were addressed in class. No longer.

The Ninth Circuit has addressed a related question about allegedly-harassing speech that is not aimed at an individual. An all-awesome panel with Justice O’Connor, and her former law clerks, Alex Kozinski and Sandra Ikuta, ruled that three racially charged emails sent by a college professors over a list-serve, that were not specifically aimed at any of the complainants, could not give rise to a harassment claim. Rather they were “directed to the college community,” and thus had wide-ranging protections of free speech. See also Gleason v. Mesirow Financial, 118 F.3d 1134 (7th Cir. 1997) (“the impact of ‘second-hand harassment’ is obviously not as great as the impact of harassment directed at the plaintiff”). Students claiming offense to something they haven’t seen personally is far too attenuated to justify an abridgment of the First Amendment.

Judge Kozinski’s analysis offers sage advice to the Univeristy of Oregon. Read it all:

Indeed, precisely because Kehowski’s ideas fall outside the mainstream, his words sparked intense debate: Colleagues emailed responses, and Kehowski replied; some voiced opinions in the editorial pages of the local paper; the administration issued a press release; and, in the best tradition of higher learning, students protested. The Constitution embraces such a heated exchange of views, even (perhaps especially) when they concern sensitive topics like race, where the risk of conflict and insult is high. See R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul, 505 U.S. 377, 391, 112 S.Ct. 2538, 120 L.Ed.2d 305 (1992). Without the right to stand against society’s most strongly-held convictions, the marketplace of ideas would decline into a boutique of the banal, as the urge to censor is greatest where debate is most disquieting and orthodoxy most entrenched. See, e.g., Gitlow v. New York, 268 U.S. 652, 667, 45 S.Ct. 625, 69 L.Ed. 1138 (1925); id. at 673, 45 S.Ct. 625 (Holmes, J., dissenting). The right to provoke, offend and shock lies at the core of the First Amendment.

This is particularly so on college campuses. Intellectual advancement has traditionally progressed through discord and dissent, as a diversity of views ensures that ideas survive because they are correct, not because they are popular. Colleges and universities—sheltered from the currents of popular opinion by tradition, geography, tenure and monetary endowments—have historically fostered that exchange. But that role in our society will not survive if certain points of view may be declared beyond the pale. “Teachers and students must always remain free to inquire, to study and to evaluate, to gain new maturity and understanding; otherwise our civilization will stagnate and die.” Keyishian v. Bd. of Regents of the Univ. of the State of N.Y., 385 U.S. 589, 603, 87 S.Ct. 675, 17 L.Ed.2d 629 (1967) (quoting Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U.S. 234, 250, 77 S.Ct. 1203, 1 L.Ed.2d 1311 (1957)). We have therefore said that “[t]he desire to maintain a sedate academic environment … [does not] justify limitations on a teacher’s freedom to express himself on *709 political issues in vigorous, argumentative, unmeasured, and even distinctly unpleasant terms.” Adamian v. Jacobsen, 523 F.2d 929, 934 (9th Cir.1975).

…

We therefore doubt that a college professor’s expression on a matter of public concern, directed to the college community, could ever constitute unlawful harassment and justify the judicial intervention that plaintiffs seek. See Eugene Volokh, Comment, Freedom of Speech and Workplace Harassment, 39 UCLA L. Rev. 1791, 1849–55 (1992). Harassment law generally targets conduct, and it sweeps in speech as harassment only when consistent with the First Amendment. See R.A.V., 505 U.S. at 389–90, 112 S.Ct. 2538. For instance, racial insults or sexual advances directed at particular individuals in the workplace may be prohibited on the basis of their non-expressive qualities, Saxe, 240 F.3d at 208, as they do not “seek to disseminate a message to the general public, but to intrude upon the targeted [listener], and to do so in an especially offensive way,” Frisby v. Schultz, 487 U.S. 474, 486, 108 S.Ct. 2495, 101 L.Ed.2d 420 (1988). See, e.g., Flores, 324 F.3d at 1133, 1135; Meritor Sav. Bank, FSB v. Vinson, 477 U.S. 57, 60, 73, 106 S.Ct. 2399, 91 L.Ed.2d 49 (1986). But Kehowski’s website and emails were pure speech; they were the effective equivalent of standing on a soap box in a campus quadrangle and speaking to all within earshot. Their offensive quality was based entirely on their meaning, and not on any conduct or implicit threat of conduct that they contained.

…

It’s easy enough to assert that Kehowski’s ideas contribute nothing to academic debate, and that the expression of his point of view does more harm than good. But the First Amendment doesn’t allow us to weigh the pros and cons of certain types of speech. Those offended by Kehowski’s ideas should engage him in debate or hit the “delete” button when they receive his emails. They may not invoke the power of the government to shut him up.

Perhaps the most troubling aspect of the University of Oregon’s recent decision is the deafening silence by the academy. There has been not a single statement by anyone at the University of Oregon raising any red flags. This should not be surprising because half of that faculty called on Shurtz to resign. Other than my blog post, I’ve seen only a few posts by Brian Leiter, Paul Caron, Glenn Reynolds, Ann Althouse, and Tom Smith, as well as a few tweets. A few professors have emailed me privately, so I suspect there are many more that are incensed by this incident. There needs to be more outrage here.

My thanks to Hans Bader for sharing a number of these helpful precedents.

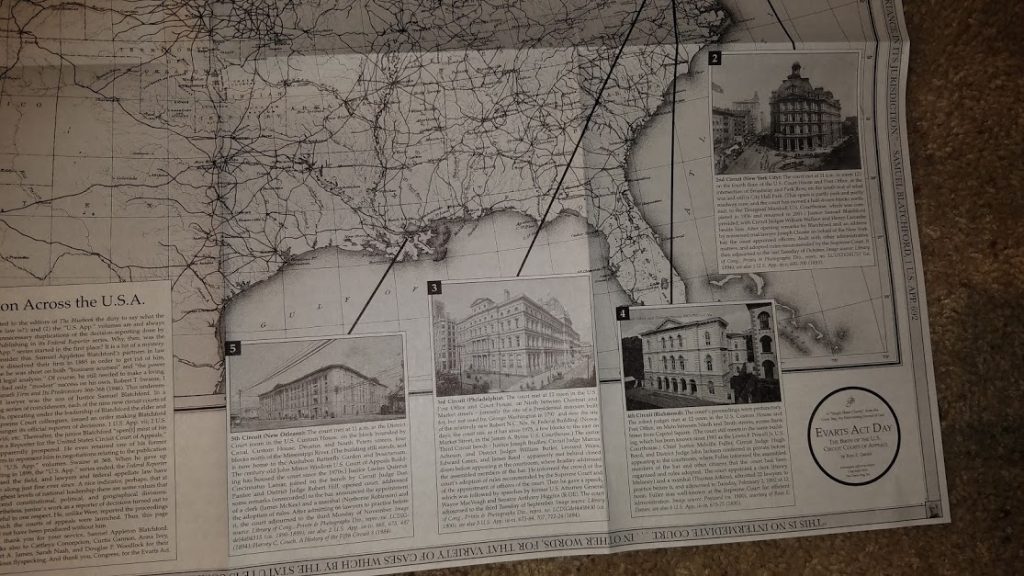

The First Circuit in Boston:

The First Circuit in Boston: