One of the bright spots of this past week is when my mom called and asked what I thought about “Emoluments.” Never could I have possibly conceived that the Emoluments Clause would be the hot topic on National Public Radio! But it is. (I could not find any coverage in the New York Times, CNN, or any major outlet when President Obama accepted the Nobel Peace Prize or when Secretary Clinton assumed a position for which she voted for a salary increase).

I admit that my view on the Emoluments Clause is somewhat of a dodge: the President is not bound by the Emoluments Clause.

This obscure clause provides:

And no Person holding any Office of Profit or Trust under them, shall, without the Consent of the Congress, accept of any present, Emolument, Office, or Title, of any kind whatever, from any King, Prince, or foreign State.

This view is admittedly idiosyncratic. In a tweet earlier this week, Larry Tribe referred to such a theory as “ridiculous,” one only a “kook” could hold.

In the 2009 OLC Opinion concerning President Obama’s receipt of the Nobel prize, now-First Circuit Judge Barron wrote that:

The President surely “hold[s] an[] Office of Profit or Trust,” and the Peace Prize, including its monetary award, is a “present” or “Emolument . . . of any kind whatever.”

No analysis whatsoever followed about why the President “surely” hold such a position. One of my biggest pet peeves in legal writing is the word “certainly,” or its close cousin, “surely.” It is conclusory language that papers over the fact that the writer hasn’t made an actual argument. Such is the case here with Barron’s opinion. Fortunately, others have given this some thought.

I have long been persuaded by Seth Barrett Tillman’s tireless research, based on the text of the Constitution, that the President is not a “person holding any office of profit or trust.” Therefore, the Emoluments Clause does not apply to him. (Seth and I collaborated on a project in 2015 concerning the related issue of the incompatibility clause, which we also do not think applies to the President).

Seth summarizes his position in the New York Times.

The Foreign Gifts Clause provides that “no person holding any office of profit or trust under them (i.e., the United States) shall, without the consent of the Congress, accept of any present, emolument, office, or title, of any kind whatever, from any king, prince, or foreign state.”

Does the Foreign Gifts Clause and its office under the United States language apply to the presidency? There are three good reasons to believe that it does not.

First, the Constitution does not rely on generalized “office” language to refer to the president and vice president. Where a provision is meant to apply to such apex or elected officials, the provision expressly names those officials. For example, the Impeachment Clause applies to the “president, vice president and all civil officers of the United States…”

Finally, in 1792, again during the Washington administration, the Senate ordered Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton to supply a list of persons holding office under the United States and their salaries. Hamilton’s 90-page responsive list included appointed officers in each of the three branches, but did not include any elected officials in any branch. In other words, officers under the United States are appointed; by contrast, the president is elected, so he is not an officer under the United States. Thus, the Foreign Gifts Clause, and its operative office under the United States language, does not apply to the presidency.

Agree or disagree, this theory is not “ridiculous,” and carries far more weight than David Barron’s conclusory “surely” analysis. To his credit, Tribe apologized, but still insisted Tillman was wrong.

Will Baude offered this gracious summary of Seth’s meticulous work:

Next time you confront a separation of powers problem or read through parts of the Constitution, keep Professor Tillman’s chart in hand. Suddenly, it will be hard to assume that the Constitution’s textual variations are meaningless. Indeed, Professor Tillman’s theory makes sense of patterns that most of us never saw. It brings order out of chaos. That is not to say that his position has been conclusively proven. But at this point, I think he has singlehandedly shifted the burden of proof.

Putting aside the Emoluments Clause for a moment, a subsidiary question is whether Congress can regulate the President’s business dealings through a statute. Yesterday in an interview with the New York Times, President-elect Trump rejected any ethical concerns about his business interests:

The law’s totally on my side, meaning, the president can’t have a conflict of interest

Almost immediately, Twitter erupted with flashbacks to Richard Nixon, who famously said “Well, when the president does it, that means it is not illegal.” As a statutory matter, he is correct. Under 18 U.S.C. 208, the President and Vice President are exempted from the conflict-of-interest law. As Josh Gerstein explains in Politico, this change was made by President George H.W. Bush.

But could Congress pass a statute regulating the President’s business interests? No. Congress can’t impose additional qualifications on the Presidency beyond those already in the Constitution, such as the Natural Born Citizen Clause. This is consistent with the Court’s holding in U.S. Term Limits v. Thornton, that states cannot impose additional criteria for members of Congress. The argument for executive independence, however, is even stronger. Individual members of Congress can easily recuse from votes that raise conflicts of interest; the President cannot.

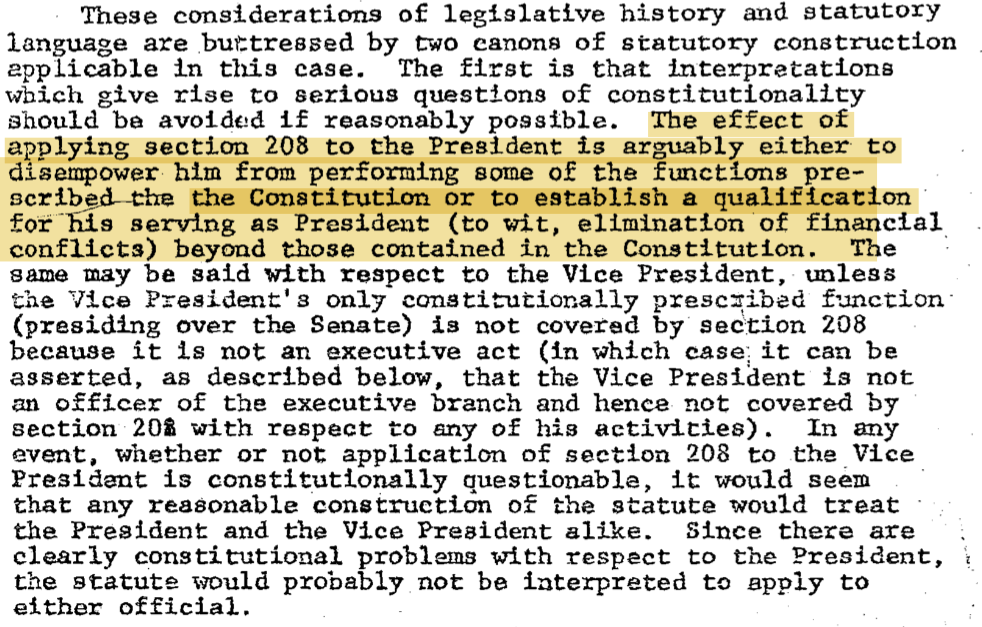

In 1972, the Office of Legal Counsel reached this same conclusion in its analysis how then-extant ethical laws impacted Vice President Rockefeller’s business interests. (The opinion was authored by then Deputy Attorney General, and now D.C. Circuit Judge, Laurence Silberman).

I think a similar analysis applies to the Supreme Court. Because the Court is created by the Constitution itself (as are the President and the Vice President), Congress can only legislate it with respect to its other constitutional authorities–such as altering the Court’s appellate jurisdiction. Regulating the Justices’ ethical duties is not one part of their enumerated powers. In contrast, Congress can ordain and establish the inferior courts, and impose whatever additional requirements it seeks.

Agreeing with me is none other than Chief Justice Roberts, who discussed this issue, obliquely, in what I called an “advisory opinion” In his 2012 annual report, Chief Justice Roberts hinted that an ethics law applying to the Court would not be constitutional.

The Code of Conduct, by its express terms, applies only to lower federal court judges. That reflects a fundamental difference between the Supreme Court and the other federal courts. Article III of the Constitution creates only one court, the Supreme Court of the United States, but it empowers Congress to establish additional lower federal courts that the Framers knew the country would need. Congress instituted the Judicial Conference for the benefit of the courts it had created. Because the Judicial Conference is an instrument for the management of the lower federal courts, its committees have no mandate to prescribe rules or standards for any other body.

This is written, perhaps intentionally, much more nebulously than the Chief usually would. But the implication is that because Congress lacks the power to create the Supreme Court (that is done by the Constitution), it lacks the power to regulate it through a code of ethics, or create a Judicial Conference to manage it. In other words, lacking the greater power to create the court implies that Congress lacks the lesser power to regulate it. I don’t find that argument, by itself, too persuasive. What the Chief was loathe to say, especially in something as innocuous as an annual report, is that the Constitution gives Congress no power to regulate the Supreme Court, only those of the lower court. Instead, he just implies this.

So here’s another thing John Roberts and Donald Trump have in common: Congress can’t regulate their private dealings, short of impeachment.

: P

: P