I blogged earlier today about the Court’s terse, five-paragraph per curiam decision in Caetano v. Massachusetts, the Second Amendment stun-gun case. Well, I called it terse. Justice Alito, joined by Justice Thomas, called it “grudging.” With good reason too. While the Per Curiam decision goes out of its way to say as little as linguistically possible to rebuke the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, Justice Alito opens fire with both barrels.

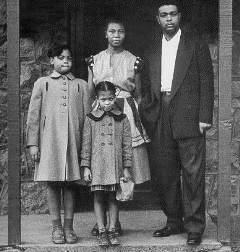

First, Alito describes the sad facts of this case. Caetano was not some sort of hardened criminal, but was a battered girlfriend, who used a stun gun (commonly known as a Taser) to defend herself against her abusive boyfriend. Rather than killing the father of her children, she used the Taser to successfully ward him off. (This is why, I suspect, the record was requested). But now, after her conviction will almost certainly be upheld on remand under some sort of wishy-washy intermediate scrutiny, Caetano will forever be barred from owning any weapon for self-defense.

Second, Alito rejected the SJC’s “bordering-on-the-frivolous” argument that because stun guns were not in existence in 1791, they were beyond the scope of the Second Amendment. Specifically, he rebuked the lower court for its flawed reliance on (our favorite case of) United States v. Miller:

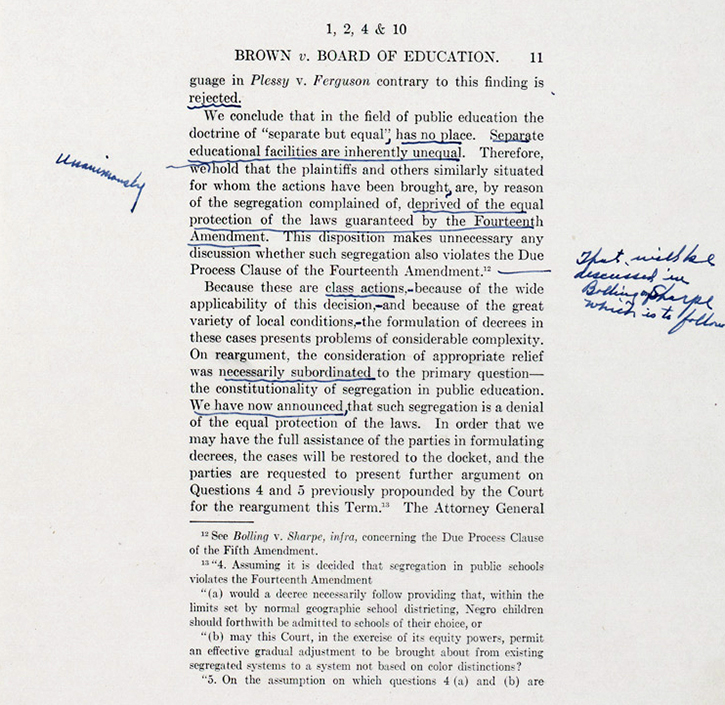

Instead, the court seized on language, originating inUnited States v. Miller, 307 U. S. 174 (1939), that “ ‘the sorts of weapons protected were those “in common use at the time.” ’ ” 470 Mass., at 778, 26 N. E. 3d, at 692 (quot ing Heller, supra, at 627, in turn quoting Miller, supra, at 179). That quotation does not mean, as the court below thought, that only weapons popular in 1789 are covered by the Second Amendment. It simply reflects the reality that the founding-era militia consisted of citizens “who would bring the sorts of lawful weapons that they possessed at home to militia duty,” Heller, 554 U. S., at 627, and that the Second Amendment accordingly guarantees the right to carry weapons “typically possessed by law-abiding citizens for lawful purposes,” id., at 625.

Third, Alito makes clear that most modern weapons–including revolvers and semi-automatic weapons–were not in existence in 1791:

While stun guns were not in existence at the end of the 18th century, the same is true for the weapons most commonly used today for self-defense, namely, revolvers and semiautomatic pistols. Revolvers were virtually unknown until well into the 19th century,4 and semiautomatic pistols were not invented until near the end of that century.5 Electronic stun guns are no more exempt from the Second Amend ment’s protections, simply because they were unknown to the First Congress, than electronic communications are exempt from the First Amendment, or electronic imaging devices are exempt from the Fourth Amendment. Id., at 582 (citing Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union, 521 U. S. 844, 849 (1997), and Kyllo v. United States, 533 U. S. 27, 35–36 (2001)). As Heller aptly put it: “We do not inter pret constitutional rights that way.” 554 U. S., at 582.

Something about this passage, with the citation to Kyllo and saying Heller “aptly put it” makes me think Scalia wrote it. Maybe, maybe not. But I got a Scalia vibe when I read it.

Fourth, the Court makes clear that “dangerous and unusual” is conjunctive, not disjunctive.

The Supreme Judicial Court’s holding that stun guns may be banned as “dangerous and unusual weapons” fares no better. As the per curiam opinion recognizes, this is a conjunctive test: A weapon may not be banned unless it is both dangerous and unusual.

Several judges, including Judge Easterbrook, have tried to separate these two, arguing that even if a gun is not unusual, but is dangerous, it is not protected.

Fifth, Alito goes into depth about what makes a gun “dangerous” for purposes of the Second Amendment. It goes without saying that all guns are dangerous. They are designed to quickly and easily inflict a mortal wound. That is their intended purpose.

First, the relative dangerousness of a weapon is irrelevant when the weapon belongs to a class of arms commonly used for lawful purposes. See Heller, supra, at 627 (contrasting “‘dangerous and unusual weap ons’ ” that may be banned with protected “weapons . . . ‘in common use at the time’”).

To Alito, so long as an arm is protected by the Second Amendment, it makes no difference of how dangerous it is. This is an interesting formulation, that I think is helpful. Many of the recent Second Amendment decisions concerning the so-called assault weapon focuses on how much carnage an AR-15 may afflict. But under Alito’s standard, if the AR-15 is protected by the Second Amendment, its lethality is irrelevant. To bolster this point, Alito makes clear that the handgun is the most dangerous gun (in terms of number of lives taken annually), so it would be the gun that ought to be banned–Heller stands for just the opposite.

Sixth, Alito stresses that even though stun guns are not quite as popular as other types of weapons, they are still protected:

While less popular than handguns, stun guns are widely owned and accepted as a legitimate means of self-defense across the country. Massachusetts’ categorical ban of such weapons therefore violates the Second Amendment.

Finally, Justice Alito offers this parting blow to the Court’s “grudging” per curiam decision.

A State’s most basic responsibility is to keep its people safe. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts was either unable or unwilling to do what was necessary to protect Jaime Caetano, so she was forced to protect herself. To make matters worse, the Commonwealth chose to deploy its prosecutorial resources to prosecute and convict her of a criminal offense for arming herself with a nonlethal weapon that may well have saved her life. The Supreme Judicial Court then affirmed her conviction on the flimsi est of grounds. This Court’s grudging per curiam now sends the case back to that same court. And the conse quences for Caetano may prove more tragic still, as her conviction likely bars her from ever bearing arms for self- defense. See Pet. for Cert. 14.

If the fundamental right of self-defense does not protect Caetano, then the safety of all Americans is left to the mercy of state authorities who may be more concerned about disarming the people than about keeping them safe.

To circle back to a point I made earlier today, why did this opinion take so long? It is possible that Justice Scalia began writing the concurring opinion, and his death slowed the process. But even then, that doesn’t explain the GVR. Is it possible the dissent from denial of certiorari pushed the rest of the Court to GVR the case? Because the Mass. SJC basically flouted the Heller decision. Although, frankly, Judge Easterbrook’s decision in the Highland Park case did exactly the same, and dared SCOTUS to overrule him. They did not.