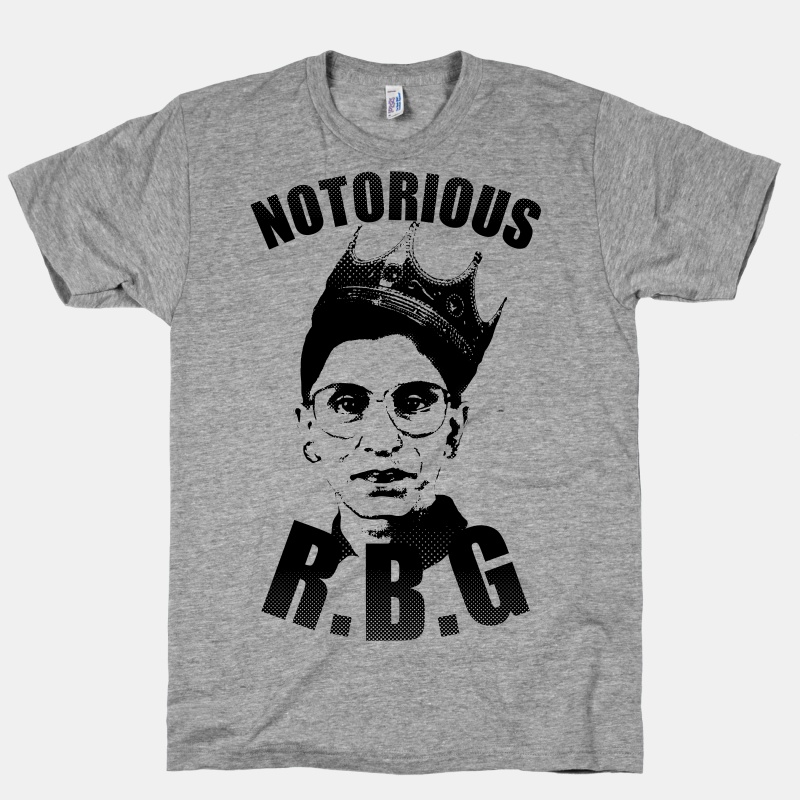

Luis v. United States considered whether the government’s freezing of a persons assets–preventing him from affording an attorney–violates the 6th Amendment’s right of counsel. The final breakdown was 5-3, however there was no opinion that commanded five votes. Justice Breyer wrote for the Chief, and Justices Ginsburg and Sotomayor. Justice Thomas concurred in judgment. There were dissents by Justice Kennedy joined by Justice Alito, and a (rare) solo dissent by Justice Kagan.

In this post I want to highlight one aspect of Justice Thomas’s concurring opinion. He explained that the government cannot prohibit certain acts that are necessary to the exercise of constitutional rights. I have written that the right to keep and bear arms is necessarily preceded by a right to make or acquire arms–preventing access to arms makes the right to keep arms a nullity. Thomas makes a similar point concerning the right to access ammunition, or the right to access firearm training. Consider this analysis:

The law has long recognized that the “[a]uthorization of an act also authorizes a neces- sary predicate act.” A. Scalia & B. Garner, Reading Law: The Interpretation of Legal Texts 192 (2012) (discussing the “predicate-act canon”). As Thomas Cooley put it with respect to Government powers, “where a general power is conferred or duty enjoined, every particular power neces- sary for the exercise of the one, or the performance of the other, is also conferred.” Constitutional Limitations 63 (1868); see 1 J. Kent, Commentaries on American Law 464 (13th ed. 1884) (“[W]henever a power is given by a statute, everything necessary to the making of it effectual or req- uisite to attain the end is implied”). This logic equally applies to individual rights. After all, many rights are powers reserved to the People rather than delegated to the Government. Cf. U. S. Const., Amdt. 10 (“The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people”).

Constitutional rights thus implicitly protect those closely related acts necessary to their exercise. “There comes a point . . . at which the regulation of action intimately and unavoidably connected with [a right] is a regulation of [the right] itself.” Hill v. Colorado, 530 U. S. 703, 745 (2000) (Scalia, J., dissenting). The right to keep and bear arms, for example, “implies a corresponding right to obtain the bullets necessary to use them,” Jackson v. City and County of San Francisco, 746 F. 3d 953, 967 (CA9 2014) (inter- nal quotation marks omitted), and “to acquire and main- tain proficiency in their use,” Ezell v. Chicago, 651 F. 3d 684, 704 (CA7 2011). See District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U. S. 570, 617–618 (2008) (citing T. Cooley, General Principles of Constitutional Law 271 (2d ed. 1891) (dis- cussing the implicit right to train with weapons)); United States v. Miller, 307 U. S. 174, 180 (1939) (citing 1 H. Osgood, The American Colonies in the 17th Century 499 (1904) (discussing the implicit right to possess ammuni- tion)); Andrews v. State, 50 Tenn. 165, 178 (1871) (discuss- ing both rights). Without protection for these closely related rights, the Second Amendment would be toothless. Likewise, the First Amendment “right to speak would be largely ineffective if it did not include the right to engage in financial transactions that are the incidents of its exer- cise.” McConnell v. Federal Election Comm’n, 540 U. S. 93, 252 (2003) (Scalia, J., concurring in part, concurring in judgment in part, and dissenting in part).

I would also highlight Thomas’s vigorous refutation of judicial balancing tests, with citations to Heller and Crawford:

As discussed, a pretrial freeze of untainted assets infringes that right. This conclusion leaves no room for balancing. Moreover, I have no idea whether, “compared to the right to counsel of choice,” the Government’s inter- ests in securing forfeiture and restitution lie “further from the heart of a fair, effective criminal justice system.” Ante, at 12. Judges are not well suited to strike the right “bal- ance” between those incommensurable interests. Nor do I think it is our role to do so. The People, through ratifica- tion, have already weighed the policy tradeoffs that consti- tutional rights entail. See Heller, 554 U. S., at 634–635. Those tradeoffs are thus not for us to reevaluate. “The very enumeration of the right” to counsel of choice denies us “the power to decide . . . whether the right is really worth insisting upon.” Id., at 634. Such judicial balancing “do[es] violence” to the constitutional design. Crawford v. Washington, 541 U. S. 36, 67–68 (2004). And it is out of step with our interpretive tradition. See Aleinikoff, Con- stitutional Law in the Age of Balancing, 96 Yale L. J. 943, 949–952 (1987) (noting that balancing did not appear in the Court’s constitutional analysis until the mid-20th century).

The plurality’s balancing analysis also casts doubt on the constitutionality of incidental burdens on the right to counsel. For the most part, the Court’s precedents hold that a generally applicable law placing only an incidental burden on a constitutional right does not violate that right. See R. A. V. v. St. Paul, 505 U. S. 377, 389–390 (1992) (explaining that content-neutral laws do not violate the First Amendment simply because they incidentally burden expressive conduct); Employment Div., Dept. of Human Resources of Ore. v. Smith, 494 U. S. 872, 878–882 (1990) (likewise for religion-neutral laws that burden religious exercise).

I do love reading solo opinions from Justice Thomas. There is always so much to think about, and so many points the majority (plurality here) can’t even attempt to respond to.