I have submitted the grades for the Constitutional Law Final Exam. You can download the exam here. Because the A+ paper was written in a bluebook–and there’s no easy way to share it–I have posted the second-highest paper (it was only two points lower, so it is a good model to study). To be frank, this was tale of two classes. The good students did really well, and the poor students did really poorly. There was not a lot in the middle.

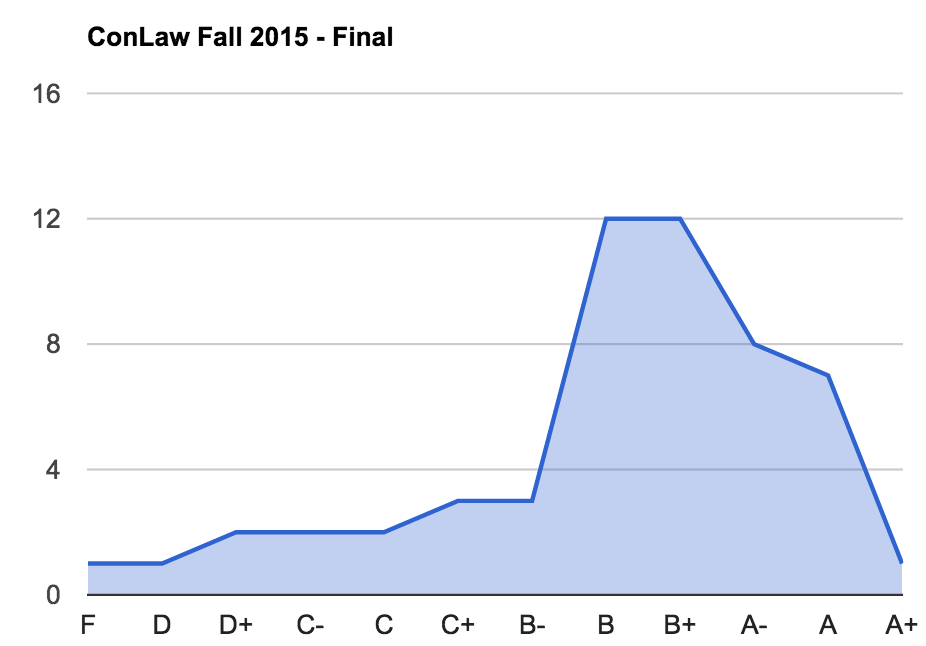

Here is the curve for the final.

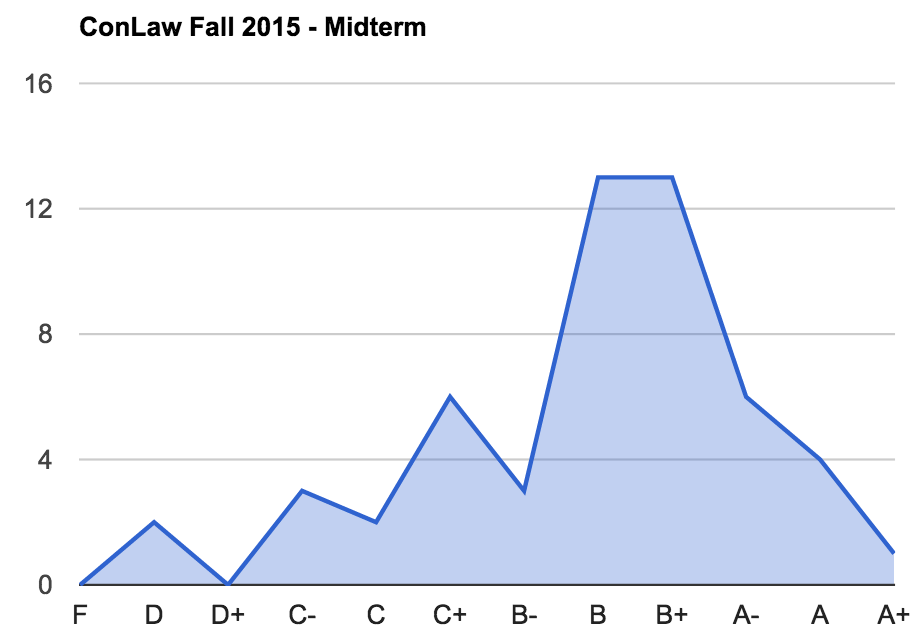

This distribution is roughly similar to that of the midterm–although a bit more smooth, telling me that there wasn’t a significant improvement for the class as a whole. In one of the few bright spots, there was some individual improvement for students who did not do well on the midterm.

Here are some specific thoughts for Question #1.

- This part was based on the Houston Equal Rights Ordinance, a topic we discussed at great length in class. I even spent class time talking about how its repeal may trigger a lawsuit based on Schuette, Romer, and the political process, which we covered before. Very, very few of you got that issue right.

- I wrote very clearly in the instructions that the bizarro-Obergefell court found that classifications based on sexual orientation were quasi-suspect, meaning intermediate scrutiny applies. The overwhelming majority of you either didn’t read that part, or decided to ignore it, as you chose rational-basis or strict-scrutiny based on your own reading of Lawrence or Windsor.

- For the most part, you remembered my discussion from class that there was no such thing as “Hate Speech,” but very few of you managed to engage the precedents to consider a content-based restriction. Although, almost all of you managed to recite the five categories of unprotected speech, which did not resolve the question.

- This question was to test if you understood a theme we developed throughout class–does the Supreme Court have a monopoly on interpreting the Constitution. I even mentioned Lincoln in the question. This was your place to shine. Inexplicably, only 25% of you even bothered to discuss Lincoln and Dred Scott in your answer.

- The final question, why do people obey courts, was our theme on the second day of class when we discussed Cooper v. Aaron, and throughout. The answers here, for the most part, reflected a lack of thought.

I wrote Question #2 before class ended, and before the Syrian refugee crisis had come to the fore. It proved to be quite propitious.

- About half of you were able to recognize that under Printz v. U.S., the federal government cannot commandeer state officials. Therefore, a Governor’s Executive Order indicating that his state officials would not assist federal officials is perfectly lawful. There may be issues where the state depends on federal funding–as reflected in the next part–but as a matter of federalism, there is no problem with this. The other half of you cited the Supremacy Clause to suggest that all federal laws trump state laws. This is wrong for this question.

- The question of whether the Syrian Refugee Act is constitutional depends on whether withholding 10% of a jurisdiction’s budget for refusal to cooperate would be considered coercive under South Dakota v. Dole, New York v. United States, and NFIB v. Sebelius. The majority of you got Dole correctly, although many said 10% of a jurisdiction’s budget would not be coercive. This is almost certainly coercie in light of NFIB.

- You may recall on the last day of class–if you bothered to attend–that one student who sits on the right side of the room, last row (from my vantage point) made a comment about having to take an oath of loyalty to the Constitution to become a citizen. At that point, I had already written the exam, so I made a point of stressing that new-citizens are required to take this oath, and I even related this back to Korematsu as as more narrowly tailored means to root out those disloyal to the U.S. I basically gave away the answer to #3, despite my statement (ironically in my mind) that I wouldn’t give any hints on the last day. In this question, people were being singled out by nationality (which is subject to strict scrutiny). I think it is a close call whether the oath requirement is narrowly tailored enough. A few of you suggested that this is compelled speech–a good point–thought in light of the fact that this is a citizenship requirement, I think it would be permissible.

- The overwhelming majority of you missed this question about the free exercise clause, which again, we covered on the last day of class. The Governor only required the oath for refugees from Afghanistan, Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Syria, or Turkey. Does anything jump out about that list of countries? As several of the top papers noted, these were all countries with large Muslim populations. In light of Church of Lukumi, even though the law was facially neutral with respect to religion, the clear purpose of the law was to single out Muslim refugees following acts of terrorism by ISIS. Thus, there is a free exercise clause violation. A number of you wrote that making someone take an oath to the Constitution would itself be a free exercise clause. This is a good idea, and one I hadn’t considered. I also gave credit for this. Since the time of our founding, people were given the option of swearing an oath, or giving an affirmation. This was an important recognition, as some religions do not permit swearing oaths. If for whatever reason you didn’t catch the Church of the Lukumi issue, you should have applied the Smith general-applicability framework. Many of you cited Sherbert and Yoder, which are no longer good law under the Free Exercise clause. (RFRA was not applicable because I wrote in the question that no claims were brought under state or federal law–only the Constitution).

- Again, this question was a policy question to allow you to shine. The answers were okay, and for the most part, repeated what you wrote in #3. In fact a couple of you actually copied and pasted your answers verbatim. This is not a good idea.

I enjoyed this class, but was disappointed by the final exams. That so many of you missed issues that weren’t in the textbook, or other commercially-available sources (when you cite cases that we didn’t cover in class, I know you are using outside sources) suggests the class discussions did not get through to you, despite the fact that they are all recorded and students (with very few exceptions) did not come to my office after class to discuss these issues.