In its sur-reply in Texas v. United States, the government attempts to spell out in some detail how DACA operates by a case-by-case inquiry. While this effort is admirable, ultimately the lack of documented dsicretion may do more harm than good.

In a previous post, I addressed the argument that the agency-wide framework is discretion. Here, I will explore the interaction between the policy and the individual officer actions. (I have put the word “discretion” in red each time it is used. I think it appears in 75% of the sentences. Reminds me of the Alan Iverson practice video).

The sur-reply explains how the policy works on “individual cases.”

And DAPA’s framework for the exercise of this discretion in individual cases helps ensure that it is not employed arbitrarily, see Defs.’ Opp. at 40 (citing cases), and that this discretion is being exercised both at a Department-level and on a case-by- case basis. Id. at 41-42.

It breaks the discretion into two steps. First “general guidelines.”

Consistent with his statutory charge to set Department-wide enforcement priorities, see 6 U.S.C. § 202(5), the Secretary in the exercise of his discretion has first established general guidelines for who may be considered—for example, having a U.S. citizen or LPR son or daughter, continuous residence for five years, and no current lawful status. These parameters, reflecting the exercise of discretion by the agency’s top law-enforcement official, are designed to ensure that the policy is limited in scope, reflects enforcement priorities, and at the same time serves a particularized humanitarian interest in promoting family unity and is consonant with congressional policies embodied in the immigration laws.

What the brief doesn’t explain is that these “general guidelines” are the entire game. If someone meets these criteria, they are effectively rubber-stamped for receipt of DAPA.

Next, the government rejects the idea that the guidance is “akin to a check-box.”

The Guidance further preserves significant judgment and discretion to be exercised on a case-by-case basis, by including broad and flexible criteria, such as whether the person constitutes a threat to public safety or whether the person presents any other “factors that, in the exercise of discretion, [would] make[] the grant of deferred action inappropriate.” Deferred Action Guidance at 4. Plaintiffs incorrectly claim that each guideline is akin to a check-box that allows no discretion, when in fact many of the guidelines, such as the public safety factor, necessarily require USCIS adjudicators to exercise significant discretion.

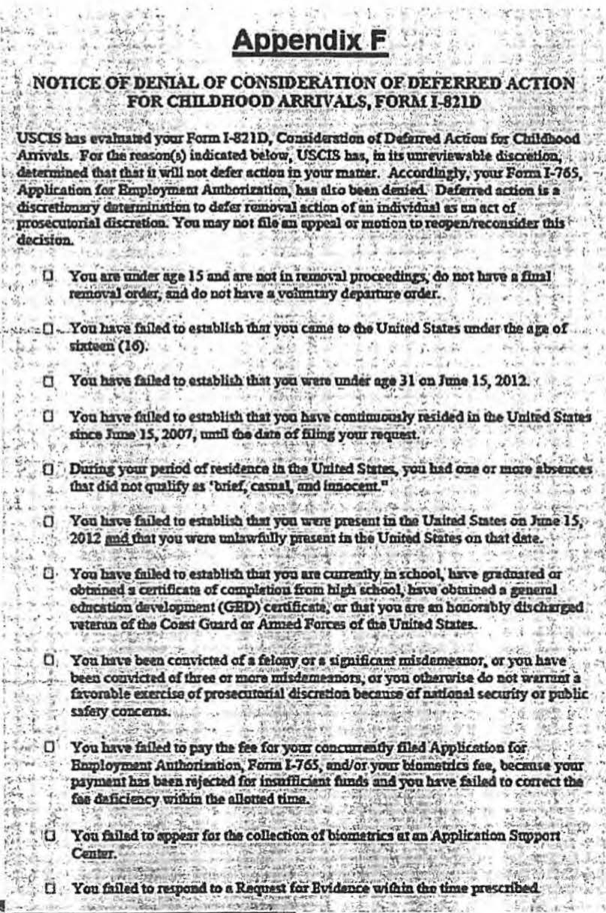

Believe it or not, this is exactly how it works. Here is the “DACA Denial Template” (that’s what it is actually called). Officers are required to check off the appropriate box to explain why a person is being denied. Note, that there is no box for “other.” USCIS officers are told they *must* use these templates and cannot deviate from them. The only grounds for denial are those established by the Secretary. This is literally, not figuratively, a checkbox.

Further, the government makes it seem like “public safety” is a discretionary factor that entails individualized judgment. The relevant check box (4th from the bottom) reads “You have been convicted of a felony or a significant misdemeanor, or you have been convicted of three or more misdemeanors, or you otherwise do not warrant a favorable exercise of prosecutorial discretion because of national security or public safety concerns.” This final factor is the only factor the government identifies from the Checklist that could be described as entailing individualized discretion.

The government tries to explain away that the template is still consistent with case-by-case review:

Plaintiffs also err when they contend that the existence of agency-wide procedures for accepting evidentiary submissions and sending notices to requestors somehow indicates that adjudicators are prevented from exercising discretion under DACA. Pls.’ Reply at 31-32. Such instructions do not indicate a lack of discretion; rather, they highlight that DACA requests must be supported by evidence presented in each case and that officers are encouraged to consider all relevant factors and evidence before determining whether deferred action is appropriate. See Neufeld Decl. ¶¶ 18-19. Likewise, Plaintiffs’ assertion that DACA involves solely the mechanical use of “templates,” see Pls.’ Reply at 32, is baseless: the portion of the DACA Standard Operation Procedures they cite in support of this claim clearly reflects that, even though standardized forms are used to record decisions, those decisions are to be made “on a case-by-case basis, according to the facts and circumstances of a particular case.” Pls.’ Ex. 10. In the end, the existence of standardized forms and procedures for administering DACA shows only that the agency has processes in place for managing work flows and for ensuring that discretion is exercised consistent with articulated enforcement priorities and in a non-arbitrary fashion.31

These templates exist for far more than “non-arbitrary” enforcement. As the rest of the documents reveal, the scope of discretion is non-existent.

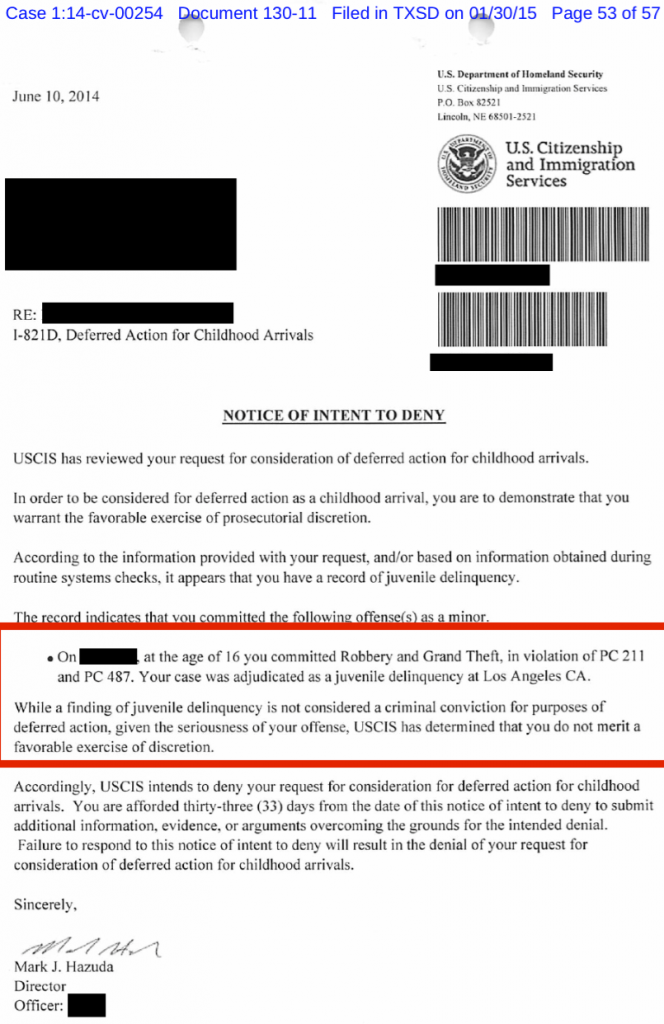

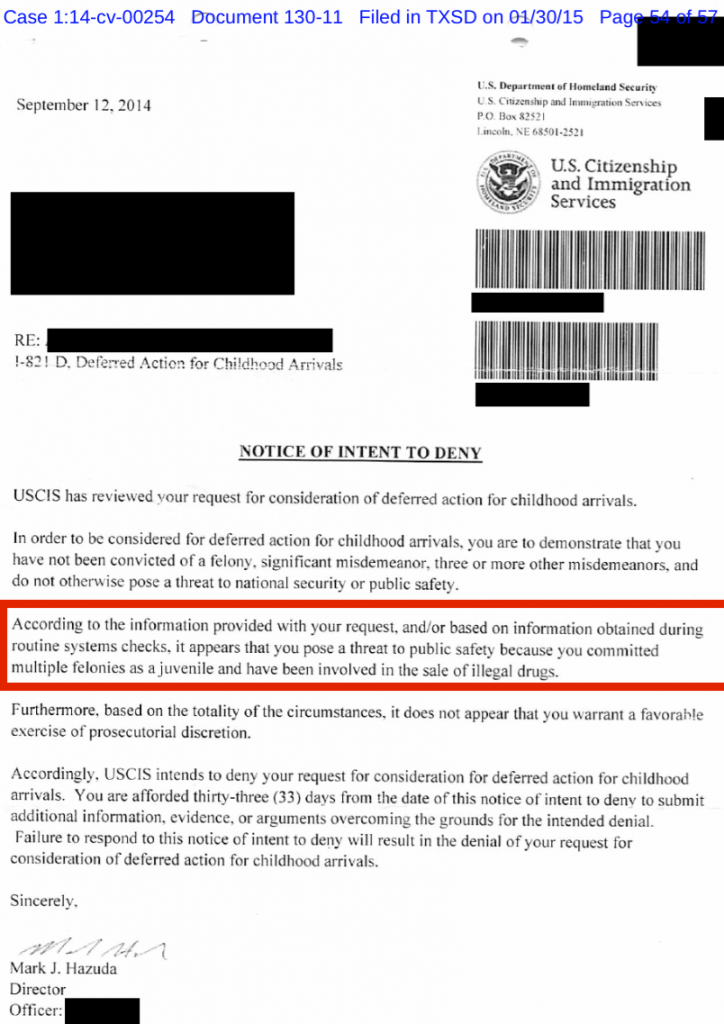

To explain that such discretion exists, the government attaches two notices of denial, citing “public safety.”

The first, dated June 10, 2014 (two years after DACA began) cites a juvenile delinquency:

“At the age of 16 you committed Robbery and Grand Theft, in violation of PC 211 and PC 487. Your case was adjudicated as a juvenile delinquency at Los Angeles CA. While a finding of juvenile delinquency is not considered a criminal conviction for purposes of deferred action, given the seriousness of your offense, USCIS has determined that you do not merit a favorable exercise of discretion.”

The second, dated September 12, 2014, cites multiple felonies as a juvenile:

“According to the information provided with your request, and/or based on information obtained during routine system checks, it appears that you pose a threat to public safety, because you committed multiple felonies as a juvenile and have been involved in the sale of illegal drugs.”

However, as Texas argues in its supplement, the only two Notice of Intents to Deny (NOIDs) provided did violate the eligibility criteria, as they involved a “felony.”

Third, Defendants gain nothing by belatedly attempting — for the first time since the creation of DACA and DAPA — to identify examples of “case-by-case discretion” under the programs. Out of 727,164 DACA applications, Defendants issued a “Notice of Intent to Deny” in only 6,496 cases (less than 1%). See Sur-reply App. 511-12. Even more remarkably, Defendants can point to only two NOIDs that were allegedly based on “discretionary” considerations (less than 0.00028%). See id. at 554-55. Moreover, in both of those allegedly “discretionary” cases, the DACA applicant did violate DHS’s eligibility criteria by “committ[ing] Robbery and Grand Theft,” id. at 554, or by “committ[ing] multiple felonies” including “the sale of illegal drugs,” id. at 555. See Memorandum for Thomas S. Winkowski et al. from Jeh Johnson, Policies for Apprehension, Detention and Removal of Undocumented Immigrants 3 (Nov. 20, 2014) (“Johnson-Winkowski Memo”) (“felony” makes applicant ineligible for DACA). Even if a 0.00028% denial rate qualifies as genuine “discretion,” it is unreasonable to call these two NOIDs “discretionary” simply because the applicants committed their felonies when they were juveniles. Sur-reply 32; Sur-reply App. 512.†

As the Secretary’s memorandum makes clear, an alien who committed a felony is a “Priority 1” threat to public safety, and not eligible for deferred action (p. 3).

aliens convicted of an offense classified as a felony in the convicting jurisdiction, other than a state or local offense for which an essential element was the alien’s immigration status; and

There is no exception for juvenile felonies. In other words, there was on judgment beyond those set out by the Secretary’s policies.

If the government wanted to make this case, it would have attached a notice that cites a factor outside the policy as the ground for denial. The fact that no such notices were attached suggests that none exist.

The government, challenging the inevitable claim that in practice there is no discretion, asserts that what matters is how it is structured, not how it is implemented.

Although Plaintiffs speculate, without foundation, that this discretion may not be implemented on a case-by-case basis, see, e.g., Pls.’ Reply at 28-32, what matters for purposes of this Court’s inquiry under Chaney is that the Deferred Action Guidance reflects multiple layers of prosecutorial discretion on a matter committed by law to agency discretion. Plaintiffs’ argument that the Deferred Action Guidance will amount to “rubber- stamping,” see Pls.’ Reply at 28-29, is also contrary to the Secretary’s policy.

When there is evidence that there is no case-by-case discretion, supported by internal training documents, Chaney will not allow the government to hide behind this façade. Specifically, if the Secretary designs a policy that appears, on its face to allow for discretion, but in practice has none, it cannot be said that the Executive is faithfully executing the law. This approach is in bad faith, and deliberately designed to mislead.

Next, the government claims that because the memorandum has not yet gone into effect, Texas cannot challenge it.

Because Plaintiffs challenge a memorandum that has not yet gone into effect, it would be inappropriate and contrary to law for this Court to assume that the Government will not administer the policy in keeping with its terms, which clearly contemplate case-by-case consideration. See USPS v. Gregory, 534 U.S. 1, 10 (2001) (“[A] presumption of regularity attaches to the actions of Government agencies”). Plaintiffs have cited no case in which a court has rejected an exercise of prosecutorial discretion by second-guessing the manner in which an agency implemented a policy that is lawful on its face, let alone based on an assumption about the agency’s presumed failure to comply with the policy as written before it has gone into effect.

The government is correct. We are in somewhat uncharted waters. No court has ever invalidated a practice based on the take-care clause. However, one could also say that DAPA is unprecedented. To the second point–that the policy has not yet gone into effect–this case will invariably have to be resolved based on the operation of DACA, as this is a pre-enforcement challenge.

DAPA and DACA are close cousins. As I explain in Part II:

To analyze the constitutionality of DAPA, we must first address its progenitor—DACA. Secretary Johnson, in establishing DAPA, “direct[ed] USCIS to establish a process, similar to DACA, for exercising prosecutorial discretion through the use of deferred action, on a case-by-case basis.” Secretary Johnson’s memorandum mirrors his predecessor, Secretary Janet Napolitano’s invocation of discretion. It begins that “DHS must exercise prosecutorial discretion in the enforcement of the law.” While DAPA has not yet gone into effect, it is safe to assume that it will adopt priorities and guidelines “similar” to those of DACA, except on a much larger scale.

The only way to understand DAPA is to look at DACA. The courts may find DAPA constitutional, but this case will not be resolved because it has not gone into effect. For once it goes into effect, there will be irreparable harm as millions of people will receive work authorizations. Based on the equities, it will be impossible to claw this back.

The fact that the government devotes so much of its brief to explaining how DACA works–something it did not do before–suggests this history will be more than relevant.