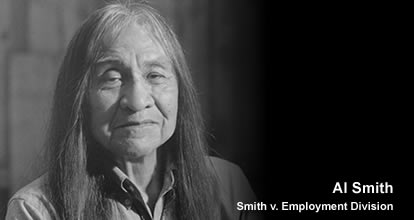

Garrett Epps notes the death of Alfred Leo Smith, the eponymous plaintiff of Employment Division v. Smith.

Garrett Epps notes the death of Alfred Leo Smith, the eponymous plaintiff of Employment Division v. Smith.

The Roseburg program hired Smith to help provide culturally relevant treatment, like the sweat lodge, to Native clients. He wasn’t looking for a landmark case; he had a wife and a new baby. He was swept into a constitutional controversy because a non-Native colleague, Galen Black, attended a peyote ceremony and told colleagues at the agency that he thought it would be a means of treating alcoholism and addiction. His bosses fired him on the spot. To the white people who ran the agency, peyote was not a religious exercise—it was an “illegal drug,” and Black was no longer fit to counsel recovering clients.

Then the bosses called Smith in and brusquely warned him that if he went to a ceremony and ingested peyote he would lose his job too. Not long after, Smith was invited to a ceremony. He had been warned, but the tone of disrespect to an Ancient Native faith rankled. He later recalled his immediate response: “You can’t tell me that I can’t go to church!”

Smith was not one to be intimidated. He attended the ceremony, took the sacrament, came back to work, and was promptly fired. Then he applied for unemployment.

The agency opposed his unemployment claim, saying the ceremonial use of peyote was “misconduct.” The state of Oregon, obsessed by the war on drugs, joined in the case (even though it wasn’t clear that Oregon law even prohibited what Smith and Black had done). State courts at every level found their conduct was protected by the First Amendment and ordered the state to pay them their benefits. The state refused to accept this, and took the case to the U.S. Supreme Court not once but twice.

At this point, attorneys for one of the many organized Native American Church groups began to pressure Smith to withdraw his claim. They feared the Court would rule against peyote use in native religious practices and set off a wave of persecution. The outside lawyers negotiated a settlement—but Oregon’s lawyers insisted that Smith and Black admit that they had engaged in “misconduct” and pay back the court-ordered unemployment they had already received.

“In the wee hours of the morning it came to me. Your kids are going to grow up and the case is going to come up one of these days and someone will say, ‘Your dad is Al Smith? Oh, he’s the guy that sold out,’” he remembered later. “I’m not going to lay that on my kids. I’m not going to have my kids feel ashamed. Even if we lose the case, they are going to say, ‘Yeah, my dad stood up for what he thought was right.’”

And you know the rest of the story. Justice Scalia’s opinion, ruling against Smith, begat RFRA, which begat Boerne, which begat RLUIPA, which begat Hobby Lobby.

It should be called Al Smith’s Law.

I was lucky enough to meet Smith in the last years of his life. He was one of the most remarkable men I have ever known. Because he knew I was writing about his case, he arranged for me to attend a ceremony. Since that experience, it’s been clear to me that only the most determinedly ignorant would mention peyote religion and “drug use” in the same breath.

Americans, and the national media in particular, live in a kind of collective fantasy they call “history,” in which things happen because of certain great men. But American history, the real history, is usually made by those outside the circles of privilege and power—people like Dred Scott, Rosa Parks, and Al Smith.

Well said Garrett. May his memory be a blessing.