National Review published my essay, “Obama’s Unconstitutional Corner,” which looks at the implications of the President’s new immigration policy. While I concede (for purposes of argument at least) that the reasoning in the OLC memo is valid in theory, I argue in practice the policy will run afoul of the limitations DOJ set down.

If we take seriously the DOJ Office of Legal Counsel’s 33-page memorandum spelling out what the president may and may not do under the auspices of prosecutorial discretion, it becomes evident that Obama’s executive action on immigration, as well as his unilateral waivers of provisions of Obamacare, exceed the scope of that discretion. The president has violated and will likely continue to violate the outer bounds that his own administration has set. By attempting to craft a limiting principle, the Justice Department has backed the president into an unconstitutional corner.

To approve this policy, OLC had to suspend its disbelief about what would actually happen. While DHS repeats the word discretion in virtually every sentence of its memo (seriously), there is very little room for discretion on the ground.

The Obama administration’s immigration policy has the effect of exempting up to 5 million people from deportation. How does it justify this non-enforcement of the law? To summarize the Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) memo, so long as the decisions not to deport “are made on a case-by-case basis,” declining to execute the law is legal. “The guarantee of individualized, case-by-case review,” the memo explains, “helps avoid potential concerns that, in establishing such eligibility criteria, the Executive is attempting to rewrite the law by defining new categories of aliens who are automatically entitled to particular immigration relief.” The last, best hope of a blanket non-enforcement policy is the appearance of an “individualized assessment.”

I say “appearance” because it is not clear that the policy President Obama announced allows for an actual “individualized assessment.” While the justification seems consistent with precedent — and OLC went out of its way to craft it that way — it is doubtful whether the policy in practice accords with this theory.

Consider DACA, which turned into a virtual rubber stamp with between 1% and 3% of applicants being denied.

Consider President Obama’s 2012 Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA). This policy exempted from deportation over 1 million minors brought to the country without authorization. Homeland Security secretary Janet Napolitano’s memo announcing DACA provided that DHS “should establish a clear and efficient process for exercising prosecutorial discretion, on an individual basis.” (This language is virtually identical to that of the 2014 DHS memo announcing the latest policy.) Yet, despite the lip service paid to case-by-case consideration, a Brookings Institution report found that only 1 percent of applicants were denied deferrals. A 1 percent denial rate, or anything in that ballpark, seems awfully close to “automatic” relief. By way of an imprecise comparison, consider that a report by the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse calculated that immigration judges denied roughly 50 percent of applications for asylum in 2010.

Further, DHS made the process of granting deferrals from deportation as lax as possible, as revealed by Freedom of Information Act requests from conservative watchdog group Judicial Watch. Specifically, field offices were asked to conduct only limited background checks, applicants without ID were still accepted for biometric processing, and there were widespread waivers of fees. Despite the insistence on prosecutorial discretion, the process seemed stacked to exempt from deportation everyone who met the bare requirements, and even those who lacked the appropriate identification or ability to pay the fees. There can be no pretense of prosecutorial discretion if DHS is wielding a rubber stamp.

DAPA, as it is now known, seems to embody the same lax approach as DACA, accept it will now apply to 4 million, rather than 1 million.

There is every reason to think that President Obama’s new policy will yield a similarly astronomically high rate of approved deferrals. In the memo from DHS secretary Jeh Johnson outlining the policy, there is absolutely no guidance about what the “exercise of discretion” should consist of and what the grounds are for rejecting an application. This must be a deliberate omission, because OLC felt compelled to acknowledge and address it. The OLC memo explains, “The proposed policy does not specify what would count as [a factor that would make a grant of deferred action inappropriate]; it thus leaves the relevant USCIS official with substantial discretion to determine whether a grant of deferred action is warranted.”

While this absence of guidance should be a cause for concern, as it violates the very theory the memo just laid out, the Justice Department is satisfied. This rationalization is unsurprising in light of the origin of the executive action. TheNew York Times reported that the administration urged the legal team to use its “legal authorities to the fullest extent.” When they presented the president with a preliminary policy, it was a “disappointment” because it “did not go far enough.” Obama urged them to “try again.” And they did just that. Politico reported that over the course of eight months, the White House reviewed over “60 iterations.” The final policy, which received the president’s blessing, pushes presidential power beyond its “fullest extent,” as it embodies discretion in name only.

I think going forward, a serviceable line for the “take care” clause should be one of prosecutorial discretion or clerical approval. The closer the process gets to the latter, the more likely it amounts to a dubious policy of non-enforcement.

The president has created criteria that apply to millions, has essentially instructed his agents to automatically check off a few boxes, and calls this an individualized assessment. Such a policy cannot be constitutional. It is designed to exempt everyone who follows the application procedure. Against the backdrop of DACA, agents reviewing applications will quickly figure out how the administration wants them to proceed. Approving such applications is not an exercise of prosecutorial discretion, but of clerical approval. Such a rote task seems a far cry from the “individualized assessment” required by Obama’s own Justice Department.

These arguments apply even more strongly to Obamacare, where Congress did not vest the President with wide latitude to suspend enforcement.

Beyond immigration, the same type of “prosecutorial discretion” was used to justify non-enforcement of Obamacare. For example, the so-called administrative fix waived the individual mandate’s penalty for anyone who believes that he cannot afford to purchase health care as required by Obamacare. In other words, just about everyone. It seems this relief was virtually automatic for anyone who requested it, without any individualized assessment. Likewise with the employer mandate, from which the administration exempted all businesses with between 50 and 99 employees until 2016. It’s unclear that any businesses that met these criteria were denied. The essence of discretion is that some applications are denied based on individual judgment. If virtually everyone’s request is granted, discretion is a mere pretense.

It cannot be the rule of law for the president to create arbitrary criteria concerning where the law will not apply and then to instruct executive agencies to exempt anyone who meets those criteria. To quote the D.C. Circuit in a 1994 decision explaining the scope of the executive’s powers, “A broad policy against enforcement poses special risks that [an agency] ‘has consciously and expressly adopted a general policy that is so extreme as to amount to an abdication of its statutory responsibilities.’” Such an abdication is an affront to Congress’s powers to write laws and the president’s oath to “take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed.”

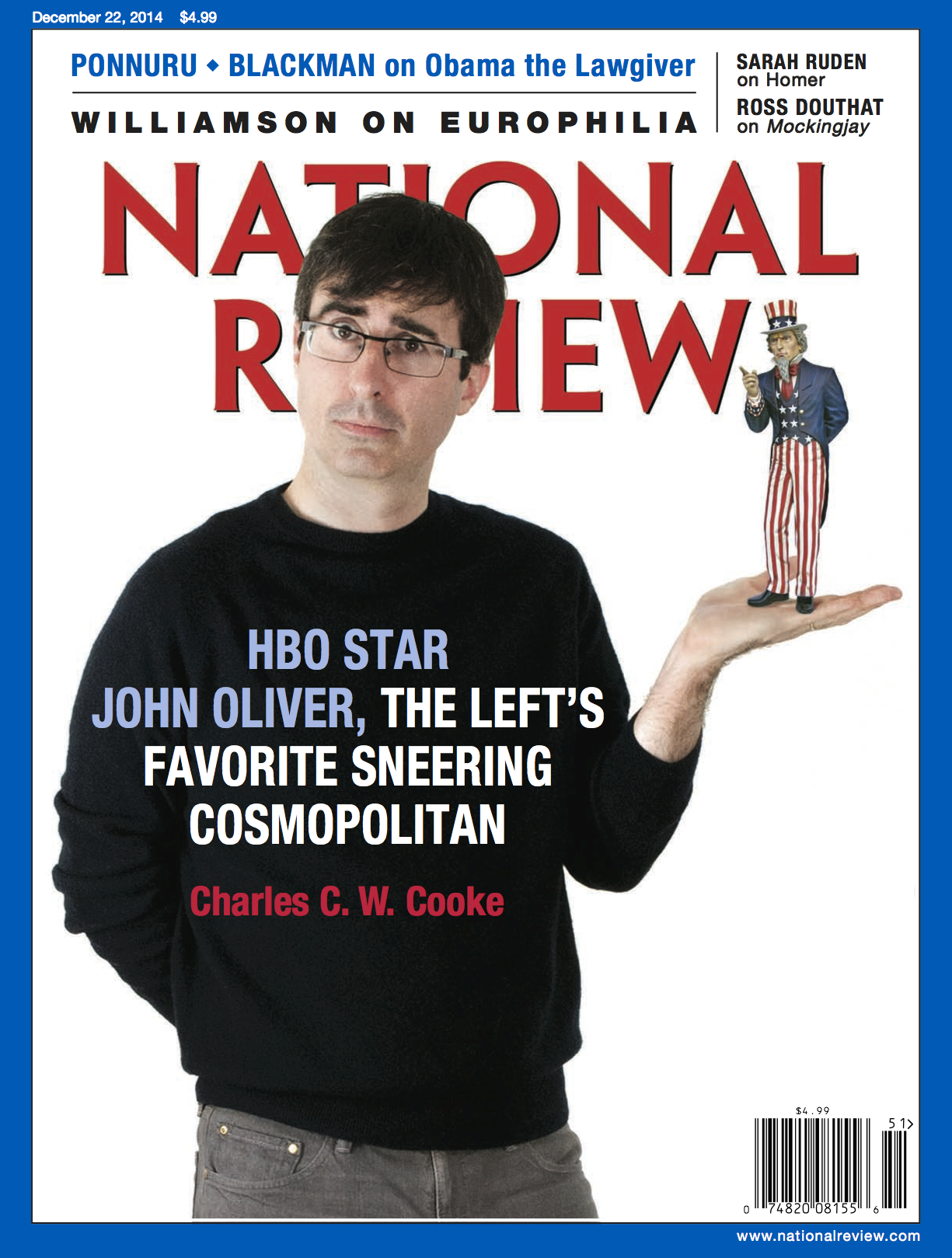

Here is the cover of the issue: