Today will be a slightly different class. We will cover Pierson v. Post, and the Case of the Spelunceuan Explorers. The focus of our class will be law and judges. Though the less will begin around the rule of capture, I hope the discussion eludes that narrow focus, and that we have a foxy talk.

The lecture notes are here, and the live chat is here.

Pierson v. Post

A few historical notes notes.

First, about the judges. Daniel Tompkins wrote the majority. He went on to serve as Governor of New York and Vice President for James Monroe. And where did Tompkins die? In a neighborhood of Staten Island, now known as Tompkinsville.

The author of the dissent was Brokholst Livingston, who later received a recess appointment to the Supreme Court from President Jefferson. He would be confirmed in 1807, and serve until his death in 1823. Livingston served a a secretary to future Chief Justice of the United States John Jay in Spain from 1779-1782.

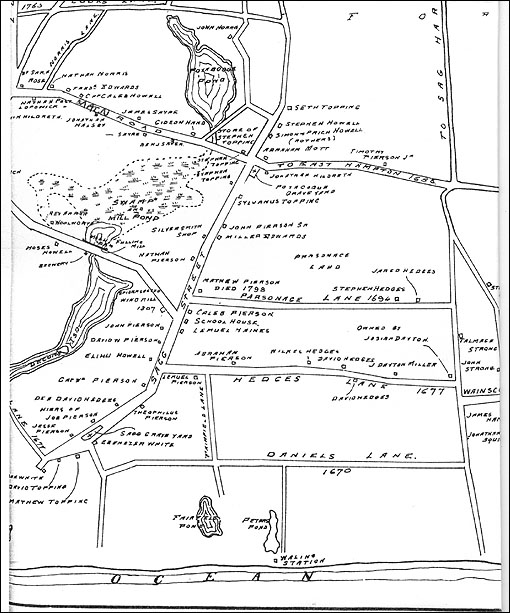

Here is a map showing Post’s home in 1800 (courtesy of Professor Angela Fernandez of the University of Toronto).

Here are some drawings of fox hunts:

Here is a video about the controversy of the fox hunt in the UK:

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DmJowswsos0]

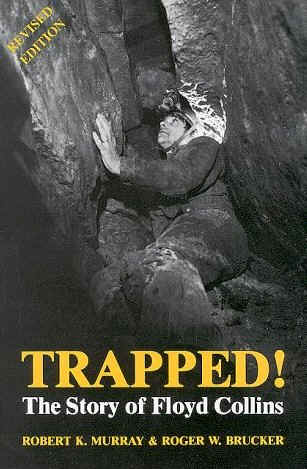

The Case of the Speluncean Explorers

After you read “The case of the Speluncean Explorers,” please vote which Justice you agree with most.

This is a picture of Lon Fuller, the author of the Case of the Speluncean Explorers.

A lot of authors have tried to write additional version of this article, but they are nowhere near as good as the original.

By the way, for you musical fans, the case of Commonwealth v. Valjean is based, of course, on Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables (Les Miz as you may know it). Jean Valjean steals a loaf of bread to feed himself and his starving sister and neice. He is arrested, and spends 19 years as a “slave to the law.” The movie version of this musical was atrocious. The singing made me cringe. If you can ever see it on Broadway, you should. It is a fantastic parable of law, morality, and ethics.

Valjean and Javert sing about the crime in “Look Down” (starts at 2:29)

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2MPbxIZpdE0]

JAVERT: Now bring me prisoner 24601, Your time is up, And your parole’s begun, You know what that means.

VALJEAN: Yes, it means I’m free.

JAVERT: No! It means you get, Your yellow ticket-of-leave, You are a thief

VALJEAN: I stole a loaf of bread.

JAVERT: You robbed a house.

VALJEAN: I broke a window pane. My sister’s child was close to death, And we were starving.

JAVERT: You will starve again, Unless you learn the meaning of the law.

VALJEAN: I know the meaning of those 19 years, A slave . . . of the law