Today Judge Randy Wilson issued the long-awaited opinion in the never-ending property saga. In short, the court denied any preliminary injunction to stop construction on the property. The court found that only damages or an injunction could issue–not both.

In this post I will focus on a few key aspects of the Court’s opinion.

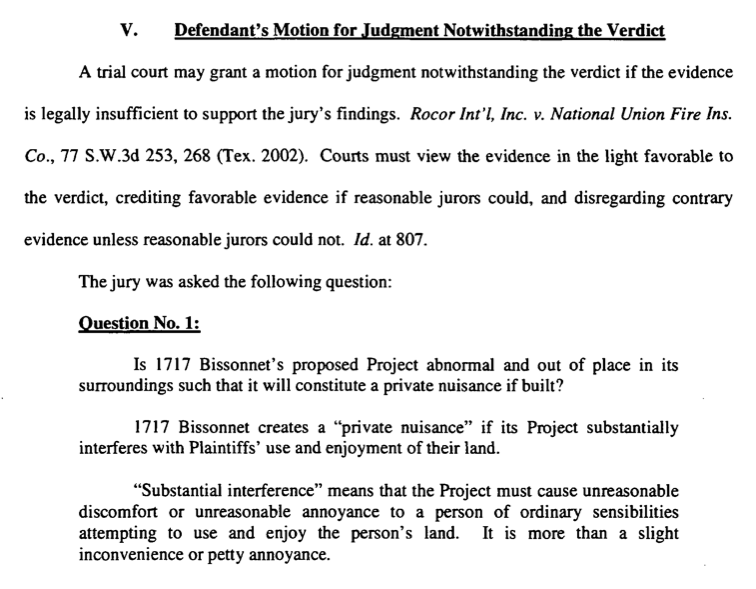

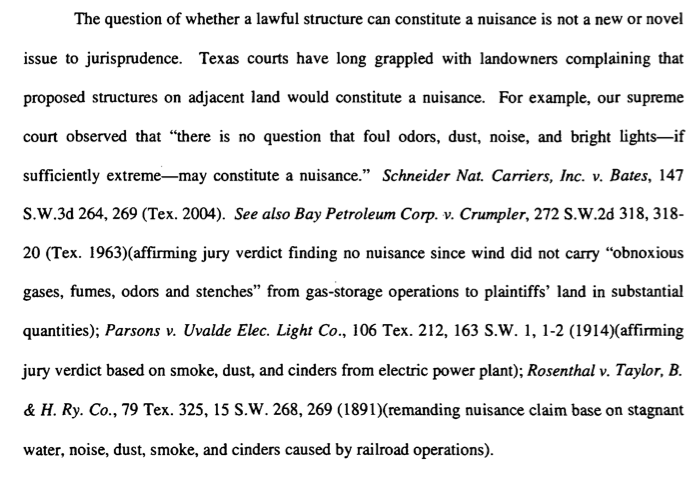

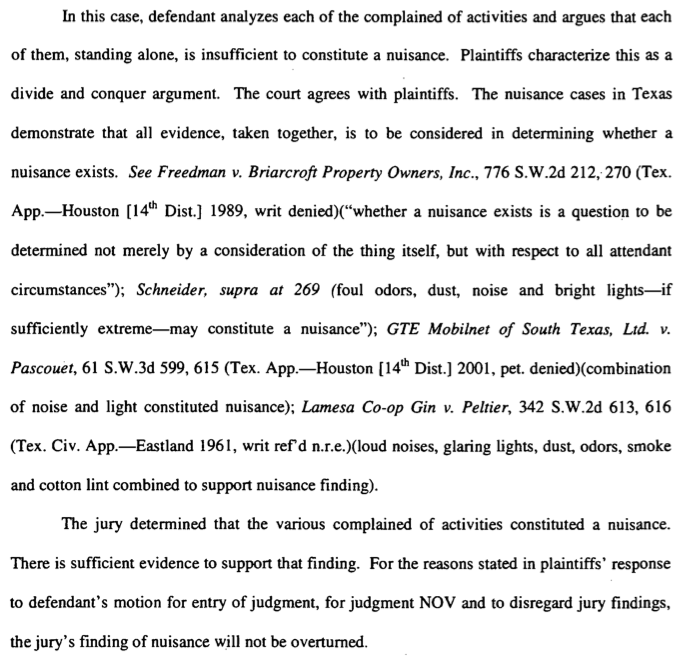

First, the court’s denied the defendant’s JNOV, finding that the jury’s finding that Ashby would be a nuisance was not erroneous. (Unfortunately, I cannot copy and paste the text, so you’ll have to settle for screen shots). Here is the court’s discussion of the instructions with respect to the JNOV.

The biggest problem with this aspect of the Court’s reasoning is that it is not supported by precedent. As I noted in this post, it is inconsistent with almost all modern-day property law to define a nuisance as something that is “abnormal and out of place.” All of the precedents the court cites conventional types of nuisances–odor, dust, noise, lights, etc. Of course nuisance law looks to the totality of the circumstances. But there is not a single precedent cited that includes as a private nuisance something that is “out of place.”

Such a definition harkens back to an earlier notion of nuisance law prior to zoning. Recall how Justice Sutherland characterized zoning in Village of Euclid v. Ambler.

A nuisance may be merely a right thing in the wrong place, — like a pig in the parlor instead of the barnyard.

It’s an odd spot, because zoning law has totally supplanted this mode of thinking about nuisance. But in Houston, without zoning, this school of nuisance law has reemerged. This is what I have referred to elsewhere as backdoor zoning. I hope the Court of Appeals clears up this issue. Even if the jury’s findings were not in error, the instructions were incorrect as a matter of law.

Second, the court reasoned that only an injunction, or damages, but not both, could be the available remedies. I am not an expert in remedy law, though I will read up on it shortly. In particular, the lead opinion cited numerous times by the Court, Schneider Nat. Carriers, Inc. v. Bates.

Third, with respect to the balancing of equities, I think the court is exactly right to reject some sort of partial injunction that would permit a building of a lower height. There were no findings by the jury about what heights would be appropriate. As I thought earlier, there is no way the Judge could split the baby in this fashion without a new trial. I also appreciate the fact that the court noted that the neighbors only filed this nuisance suit as a last-ditch effort after four years of fighting Ashby. This generated significant hardships for the builders.

The court made special note that granting the injunction would have a “chilling effect” on development. It also acknowledge’s that “for better or worse, the City of Houston has repeatedly opted against zoning. Houston’s lack of zoning is often touted as part of the DNA of the city.” The court also cited, but not by name, the testimony of my colleague Matt Festa, who testified at trial. Houston, though it has no zoning laws, “vigorously enforces its ordinances and codes.”

The greatest danger of using nuisance law to police land-use, is that there is no way, ex ante, for developers to know what the law requires. “If an injunction was issued, then a judge can become a one man zoning board with little criteria. Two different courts could examine two similar projects and reach contrary conclusions. Even after developers obtained a building permit, developers would have no idea whether a proposed project judicial scrutiny.” The court observed, “while building codes and ordinances are quite detailed, the criteria of what constitutes a nuisance is considerably less specific. Here the definition of nuisance is simply whether a project, if built, would be abnormal and out of place in its surroundings.” I suggest this is not the correct definition of nuisance, and the problems of granting an injunction illustrate the wrongness of this instruction.

Like the Phoenix, the Ashby High Rise has risen from the ashes, once again. That is, until the appeal begins.