The lecture notes are here. The live chat is here.

Scope of Federal Powers III

- Taxing Power (637-643).

- The Spending “Power” (643-645).

- United States v. Butler (645-648).

- South Dakota v. Dole (648-656).

- New York v. United States (657-670).

- Printz v. United States (670-683)

Baiely v. Drexel Furniture Co. (The Child Labor Tax Case)

The Drexel Furniture Company was established on November 10, 1903 in Drexel, North Carolina. B

By 1968, after several acquisitions, the company became known as the Drexel Heritage Furnishings, Inc. It is still known as that today.

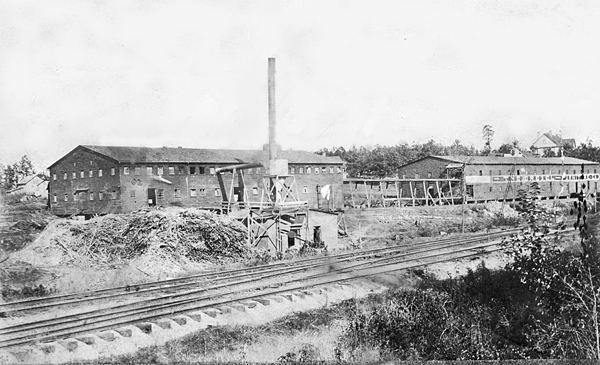

Here is a photograph form 1906 of the Drexel Furniture Company in Drexel, North Carolina that employed child laborers.

The company’s first plant burned in 1906. The plant pictured was built in two weeks after the fire and was identical to the first one. The plant consisted of two buildings. In 1917, the building got electricity. An addition was added in 1918.

Steward Machine Company v. Davis (1937)

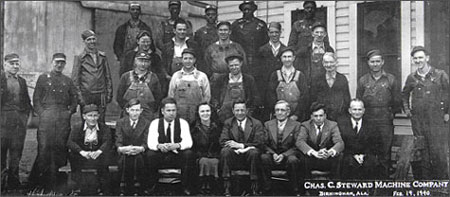

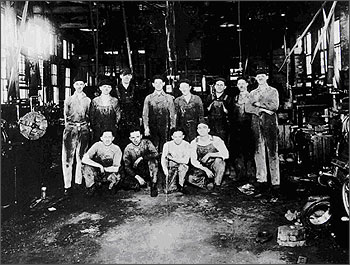

The Steward Machine Company, based in Birmingham, Alabama, challenged the constitutionality of the social security tax cases. The company was founded in 1900. Here is one of their first facilities.

I think this photograph is dated February 19, 1900, but it is too blurry to make out for sure.

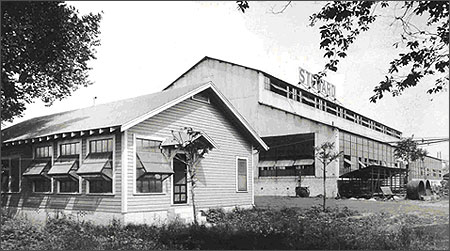

Here is their modern-day image.

United States v. Butler

This is President Roosevelt signing the Agricultural Adjustment Act into law.

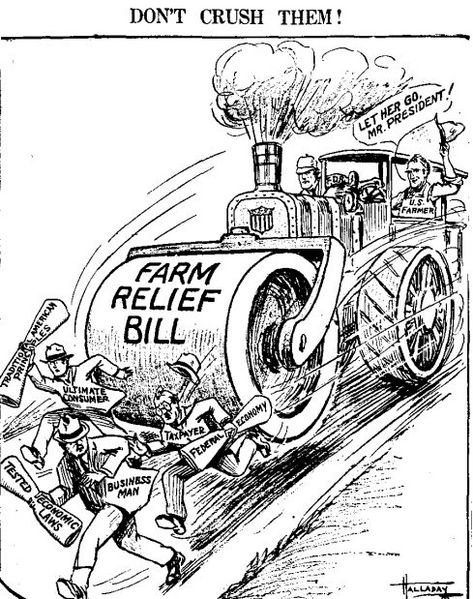

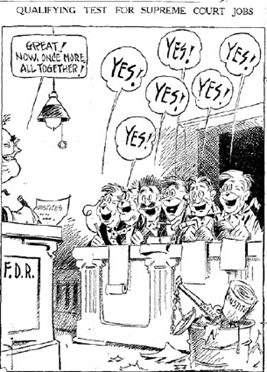

And some cartoons.

South Dakota v. Dole

This case involved Secretary of Transportation Elizabeth Dole, whose husband (Viagra spokesman) Bob Dole, was a long-time Senator from Kansas, and Republican nominee for President in 1996.

Printz v. United States

The case of Printz v. United States was brought by two sheriffs. Sheriff/Coroner Jay Printz of Ravali County, Montana, and Sheriff Richard Mack of Graham County, Arizona. Both were the Chief Law Enforcement Officers (CLEO), subject to the background-check mandate of the Brady Act’s National Instant Criminal Background Check System. Printz was represented by Stephen Halbrook, and Mack represented by David Hardy.

I’ve spoken to both plaintiffs, and they are very interesting officers–they certainly look the part of CLEOs. Mack insists that the case should be called Mack v. United States, because his name came first alphabetically (docket numbers be damned!).

Following this case, Jay Printz would serve as Sheriff until 1999, and then became a member of the Board of the National Rifle Association. Richard Mack ran unsuccessfully for Congress in Arizona and Texas.

From left to right: Atty. Dave Hardy; Sheriff Richard Mack, Arizona; Sheriff Sam Frank, Vermont; Atty. Stephen Hallbrook; Sheriff Printz, Montana.

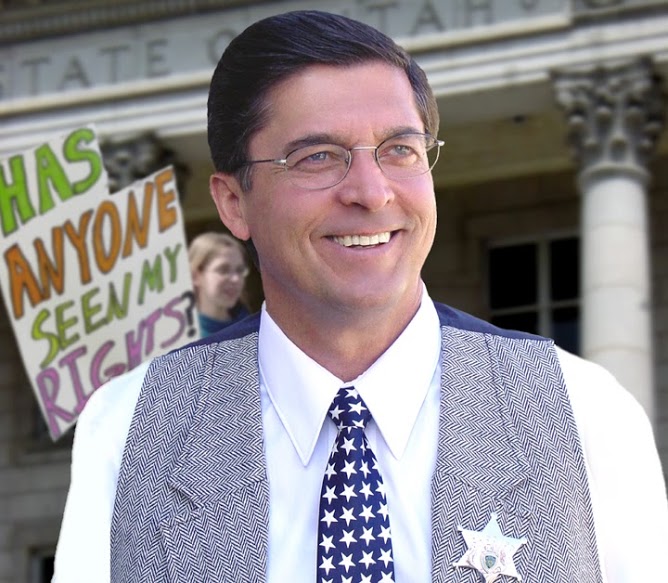

Sheriff Richard Mack at the Utah Capitol.

Stephen Halbrook arguing Printz v. United States. Note Justice Scalia has a hipsteriffic beard.

More pictures of Sheriff Printz