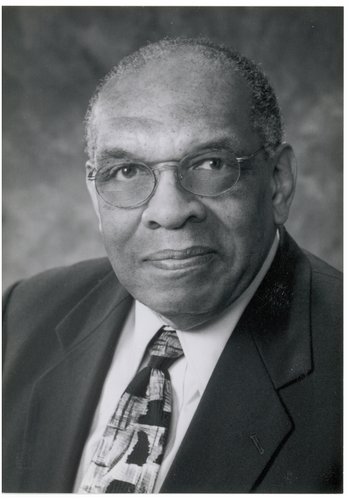

Alton T. Lemon, the eponymous plaintiff in Lemon v. Kurtzman, has passed away. Adam Liptak has a great obituary.

Alton T. Lemon, the eponymous plaintiff in Lemon v. Kurtzman, has passed away. Adam Liptak has a great obituary.

Lemon had some wise words about his actual role in the case–not much (other than giving Justice Scalia fodder for some awesome puns).

Mr. Lemon, for his part, said he was surprised to have lent his name to a leading piece of First Amendment jurisprudence. “I still don’t know why my name came out first on this case,” he told The Philadelphia Inquirer in 2003.

…

Mr. Lemon attended the Supreme Court argument in his case, but he found the experience a little alienating. “When your case gets to the Supreme Court, it’s a lawyer’s day in court,” he said. “It doesn’t matter to the justices if you are dead or alive.”

So is Justice Scalia’s concurrence in Lamb’s Chapel, talking about a dead Lemon rising from the grave, now the making of a zombie flick?

s to the Court’s invocation of the Lemon test: Like some ghoul in a late night horror movie that repeatedly sits up in its grave and shuffles abroad, after being repeatedly killed and buried, Lemon stalks our Establishment Clause jurisprudence once again, frightening thelittle children and school attorneys of Center Moriches Union Free School District. Its most recent burial, only last Term, was, to be sure, not fully six feet under: our decision in Lee v. Weisman, 505 U. S. —-, —- (1992) (slip op., at 7), conspicuously avoided using the supposed “test” but also declined the invitation to repudiate it. Over the years, however, no fewer than five of the currently sitting Justices have, in their own opinions, personally driven pencils through the creature’s heart (the author of today’s opinion repeatedly), and a sixth has joined an opinion doing so. . . .

The secret of the Lemon test’s survival, I think, is that it is so easy to kill. It is there to scare us (and our audience) when we wish it to do so, but we can command it to return to the tomb at will. See, e. g., Lynch v. Donnelly, 465 U.S. 668, 679 (1984) (noting instances in which Court has not applied Lemon test). When we wish to strike down a practice it forbids, we invoke it, see, e. g.,Aguilar v. Felton, 473 U.S. 402 (1985) (striking downstate remedial education program administered in part in parochial schools); when we wish to uphold a practice it forbids, we ignore it entirely, see Marsh v. Chambers, 463 U.S. 783 (1983) (upholding state legislative chaplains). Sometimes, we take a middle course, calling its three prongs “no more than helpful signposts,” Hunt v. McNair,413 U.S. 734, 741 (1973). Such a docile and useful monster is worth keeping around, at least in a somnolent state; one never knows when one might need him.

Alas, I am not a big fan of how the Lemon test has been applied.