Update: Several updates below, including a comment from another EIC at a Tier I Law Review, and a former anonymous member of the California Law Review.

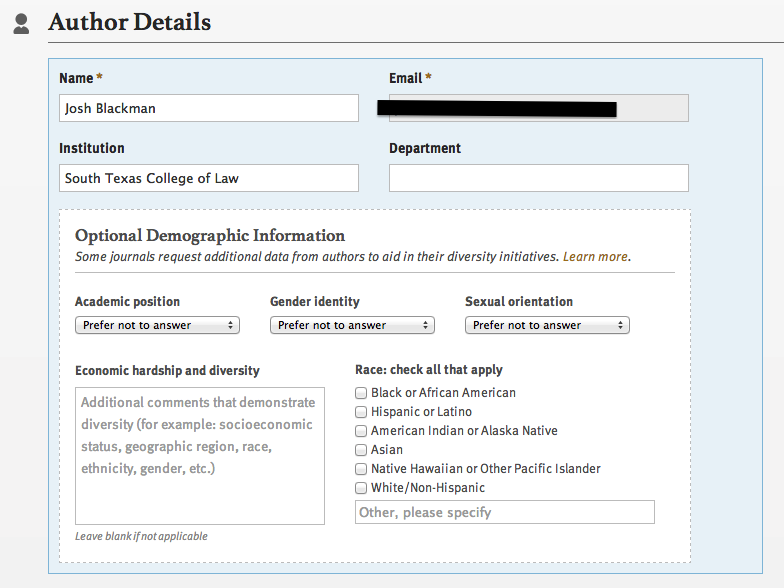

I recently discovered that Scholastica, a competitor to Expresso in the electronic journal submission process, allows authors to submit demographic information, including an author’s gender identity, sexual orientation, race, and a box to explain “economic hardship and diversity” (it suggests “Additional comments that demonstrate diversity (for example; socioeconomic, status, geographic region, race, ethnicity, gender, etc.”). Dave Hoffman also blogged about it at Concurring Opinions.

While Scholastica stresses that this information is optional, three journals–California Law Review, U.C. Davis Law Review, and the Boston College Law Review–“ask” authors to submit this demographic information. (A slight bit of irony. Expresso is based out of the Berkeley Electronic Press. The California Law Review, the flagship law review of the UC System, based at Berkeley, has opted out of using Expresso).

I contacted each of the three journals and asked for an explanation of how they are using this demographic information.

I haven’t received a response from Boston College (I would be happy to post one). The response from U.C. Davis was reassuring. The response from U.C. Berkeley was not.

The editor from the U.C. Davis Law Review told me that they are only collecting the data to get a sense of who is submitting to the journal, and would only consider “general statistics instead of knowing how each author responded.” In other words, they would receive aggregated statistics of who is submitting to the journal, but would not look at each individual author’s demographics. She reassured me that they would not use these demographic factors during article selection.

The Editor in Chief from the California Law Review was more evasive with her answers. I paste the complete exchanges at the end of this post below the jump, but I will summarize them here.

First, the EIC described a holistic approach to selecting articles where they are committed “to discovering and promoting less established scholars that may not yet have the cachet to catch the notice of other top law reviews.” As an author at a not-top law school, I agree with that goal. It would seem easy enough to determine which authors lack this cachet. Take a look at the C.V. and previous law review placements. But here the journals veers off. She noted, “Each articles board uses available information in different ways, but ultimately our mission is to publish the best legal scholarship possible and we believe that maximizing the information that our editors have access to increases the quality of our selections process.”

Specifically, the EIC writes, “added information about our authors helps us to get a better sense of what impact, if any, publishing with CLR might have.” I assume she meant that the “added information” was race, gender identity, and sexual orientation. This led me to the think that the journal can fact use race, as one of many factors, in a holistic approach (call it Grutter rather than Gratz).

I asked her to clarify in a subsequent email, and her response again was vague.

CLR has never had a “blind” selection process and few, if any, law reviews purport to use blind submissions. Each articles board has to decide how, if at all, they will use additional information about an author or his or her scholarship on a case-by-case basis.

She also noted that the journal looks at “secondary factors.”

In trying to achieve that mission, we consider secondary factors–like all journals–of whether an author has published with us before or recently, whether we’ve published in that particular area of scholarship already in the current volume, and, perhaps uniquely to CLR, whether publishing with us would have an impact on the author’s career.

I can’t tell from her email if race can be one of the “secondary factors,” but based on the full context of the email, in response to my questions about race, I would infer it is (you can read the complete email below).

Whether race is actually used, I cannot say, but the EIC’s two responses do not foreclose that possibility. In fact, her decision not to answer the question directly (in contrast with the U.C. Davis Law Review), even when I gave her another chance to answer directly, leads me to believe that this may have happened. A clear, non-lawyerly “yes” or “no” answer here would have been preferred.

The related question is whether an author who declines to submit this information will be penalized. The EIC says no:

We only have one cycle’s worth of data and even that is fairly limited because many authors chose not to provide additional information. Again, that choice has no bearing on whether and how we consider a piece.

This is only true if race is not used as a plus factor. Because, by simple logic, if some authors with certain demographics are given a plus factor, assuming a fixed number of articles to publish in a volume, authors who choose not to submit that information cannot get that plus factor (and not getting a plus factor is no different than a minus factor). I doubt this will matter much at a single journal, but I can imagine if this practice catches on, the problem may be magnified.

One additional issue. Because the California Law Review is housed at a public institution in California, it is subject to Prop 209. Prop 209, enacted in 1996, bans the consideration of race in public employment. The 9th Circuit upheld Prop 209 as constitutional. Recently, the 6th Circuit struck down a similar provision passed my Michigan. (Disclosure: I clerked on the 6th Circuit when that case was argued). Michigan has already filed for cert. With Fisher coming down the pike, Prop 209 may soon become the law of the land.

The relevant section is (a), which provides “The state shall not discriminate against, or grant preferential treatment to, any individual or group on the basis of race, sex, color, ethnicity, or national origin in the operation of public employment, public education, or public contracting.” I am not familiar enough with the contours of Prop 209, but to the extent that the journal at a state school, which would seem to be “in the operation of . . . public education,” considers race when selecting articles, there may be a conflict with Prop 209. [Update: A colleague mentioned that if any symposium authors are paid honorariums, and those authors were selected with race as a consideration, the payment may implicate the “public employment” provision of Prop 209.]

I hope that other journals do not follow this lead, and perhaps the California Law Review reconsiders this policy.

The complete emails below the jump.

Update: Dave Hoffman writes at Concurring Opinions:

As several commentators noted (most in private emails, because they are afraid of negative consequences in the submission market), a very disturbing aspect of Scholastica’s new submission process is that it appears to facilitate and encourage law reviews to use sexual orientation, race, and gender in selection decisions. Josh Blackman has investigated, and written a very useful follow-up post which I hope you all will read.

My own view is that whatever the merits of law reviews giving “plus” points to authors at less prestigious schools,* providing plus points on account of race, gender, and sexual orientation is a terrible, terrible practice, especially if the plus points are awarded in an opaque manner by a largely unsupervised student board at an instrumentality of the state. Scholastica appears to take the position that it’s just giving journals what they want here. Would it feel the same way if journals were planning to use sexual orientation and race as negative factors? (Which, from a certain perspective, is exactly what they may be planning on doing.)

Update 2: An Editor-In-Chief from a Tier I Law Review that is moving to Scholastica writes in to tell me they requested that Scholastica remove the question that asks for this demographic information. The EIC also assured me that the journal never uses race in any way when selecting articles. This is reassuring.

We’ve never used demographic information to select articles in the past. We don’t ask for it, we don’t utilize it, when it’s offered we don’t retain it. Our move to Scholastica hasn’t changed that. Our first instinct was to simply remind authors that the box is labeled “optional,” and that they should feel free to disregard it. But one of our editors pointed out that some authors may be troubled even by the prospect of leaving the box blank, fearing that doing so would be frowned upon and may place the author at a disadvantage.

We contacted Scholastica this afternoon. They were remarkably responsive and cooperative (as they’ve been since we first began working with them). They agreed to simply remove that box from our interface, and assured us that the change would happen within a day or two.

We shifted to Scholastica specifically because we believed it would lead to a better experience for our authors. We believe it provides tools that will allow us to reduce our turnaround time, better track expedite requests, and improve continuity throughout the publication process. It would be disappointing if that move alienated or frustrated the very group we meant to better serve.

This is very reassuring. The mere fact that the demographic information is asked for creates a negative stigma about leaving it blank. I’m glad to see Scholastica is fixing this problem.

Update 3: A commenter who claims to have been a former member of the California Law Review writes in to say that race, gender and orientation have been used during the article selection process for some time.

As someone who worked on CLR several years ago, I can say with some confidence that consideration of race, gender, and orientation in the article selection process is nothing new and not exactly a secret. I have never been particularly comfortable with this fact, and find the lack of transparency in the current EIC’s responses unfortunate.

This confirms my suspicion of why the EIC was so obtuse with her answers. I would wager that other schools also do this, albeit secretly. If this is such an important interest, journals should be transparent about it, and perhaps release a diversity policy to articulate why and how this process is being used. It is perhaps fortunate that Scholastica put the question out in the open by asking authors for it directly.

Update 4: An EIC of a journal writes to tell me that they requested that Scholastica no longer ask for the demographic information for submissions to their journal, and Scholastica pretty much complied (as much as feasible). As it stands now, NYU and California still ask for this information.

Just a quick update. Scholastica has made the change we requested.It’s a little complicated because of the way their interface works–authors first select the journals they want to submit to and then are asked to provide information (name, manuscript title, and–before tonight–diversity info). As you know by now, there are two journals that have explicitly stated that they want that information–Cal and NYU. If an author’s list includes either of those journals, they’ll still be asked for optional diversity info, with an attached note making clear which journals are asking for that info. If, on the other hand, an author submits only to Iowa, they will no longer see that box at all–we don’t want that info and don’t want Scholastica asking authors for it on our behalf. In fact, authors can submit to as many Scholastica journals as they want and not see that box–as long as they don’t include Cal or NYU on their lists.It’s not a perfect solution, but I hope it shifts the focus to where (in my opinion, at least) it should have been from the start–on the journals who ask for that information and incorporate it in their selection decisions, not on the service that conveys that request.

In other words, the demographic information is not requested unless NYU and California are selected. If one of those two are selected, you receive an additional warning above the box concerning the Demographic information that reads:

Optional Demographic Information

You are seeing this section because you are submitting to California Law Review.

This journal allows authors to provide optional demographic data. Any answers will be shared only with California Law Review.

Interestingly, Boston College and U.C. Davis were on that list. Now they are no longer on the list. But added to the list is NYU

Some journals hosted on Scholastica request optional demographic information (e.g. race, gender, sexual orientation, etc.) from authors when they submit a manuscript. Optional demographic data collected in the manuscript submission form will be made available to journal editors only, and optional demographic data will be stored with the manuscript submitted to that journal. Journals which do not request optional demographic information at the time of submission will not have access to this data. Authors are not required to submit optional demographic information in order to submit a manuscript to a journal on Scholastica. The choice to request this data is made explicitly by the journal, and use of the data is entirely the responsibility of the journal collecting the data. Scholastica will store the data on the journal’s behalf and allow journals to collect and analyze data, but Scholastica will not sell, trade, or transfer an individual’s personal information to any third party or entity.

Journals who allow authors to submit demographic information:

- California Law Review

- New York University Law Review

I’m glad Scholastica updated the feature so quickly. I’m also glad U.C. Davis and Boston College dropped off the list. Curious why NYU joined. But not surprising that Cal remains.

Update 5: Boston College Law Review writes in. They had requested the information, but “disabled the demographic information module last week in response to concerns from the academic community.”

(1) How long have you been collecting this information?The Boston College Law Review only very recently switched from ExpressO to Scholastica, on February 1st. Consequently, we had also only been collecting demographic information for that short period of time.(2) Why did you decide to ask for it?The current Editorial Board of the Boston College Law Review is interested in examining the diversity of our scholarship (and our membership) over time. We thought that collecting voluntarily disclosed demographic information from those who submit manuscripts to us could help us better assess the characteristics of those whom we publish and could prove useful to future Editorial Boards. We disabled the demographic information module last week in response to concerns from the academic community.(3) Have you ever released statistics, or do you have plans to release them?We have no plans to share the data we collect publicly, especially because the collection of this data is so new.(4) Is this information used in the article selection process?We do not rely on the demographic information (or an author’s choice not to share it) in our article selection process. Our decision to collect demographic information is not intended to signal any change from the way we have conducted article selection in the past.

My initial email to California Law Review

On Scholastica, your journal is one of three that asks authors to submit demographic information, including gender identity, sexual orientation, race, and and other information about economic hardship and diversity.I haven’t seen this request on any other journal submissions.If I may ask a few questions.How long have you been collecting this information?Why did you decide to ask for it (I understand it is not required, but you signaled a preference for submitting the information)?Have you ever released the statistics, or do you have plans to release them (the data may be of some interest to the academic community)?Is this information used in any way during the article selection process?I appreciate your attention to this.Josh Blackman

Thank you for your inquiry. The California Law Review is committed to publishing cutting-edge legal scholarship and we take our selections process quite seriously. We encourage all submitting authors to provide additional, optional demographic information and began collecting this information last fall. We ask for this information for a variety reasons, e.g., it allows us to track who we are publishing. Additionally, we pride ourselves on our commitment to discovering and promoting less established scholars that may not yet have the cachet to catch the notice of other top law reviews and added information about our authors helps us to get a better sense of what impact, if any, publishing with CLR might have. It is also an opportunity for authors to elaborate on information that may be on their CVs, or to include relevant information that would be out of place on a CV.Because this is a rather recent initiative, we have not released any of this information and do not have any plans to do so. Not all authors choose to provide additional information and their choice has no bearing on our selection process. Each articles board uses available information in different ways, but ultimately our mission is to publish the best legal scholarship possible and we believe that maximizing the information that our editors have access to increases the quality of our selections process.

I appreciate your holistic approach to article selection. I also applaud your efforts to give less-established authors a chance to publish in such a fine journal. Also I recognize that the choice to not provide the information has no bearing on your process.But how is it used for those who supply the information? You did not directly answer whether the demographic factors, when provided, can be a factor in selecting articles. I’ll assume based on your answer, unless you tell me otherwise directly, that the demographic information and other may be used, in some fashion or another, depending on the circumstances.Also, I’m not exactly sure what “added information about our authors helps us to get a better sense of what impact, if any, publishing with CLR might have” means. Do you mean the impact on the author? Or the impact on the journal by publishing that author? If its the latter, do you mean to say that publishing people with certain demographics might impact how the journal operates, or how the journal is perceived?I really appreciate your attention to this.Thanks!

We do not have an official policy on how any data that we collect gets used or not used by our articles board. CLR has never had a “blind” selection process and few, if any, law reviews purport to use blind submissions. Each articles board has to decide how, if at all, they will use additional information about an author or his or her scholarship on a case-by-case basis. The sole mission of our articles board is to publish the best available scholarship. In trying to achieve that mission, we consider secondary factors–like all journals–of whether an author has published with us before or recently, whether we’ve published in that particular area of scholarship already in the current volume, and, perhaps uniquely to CLR, whether publishing with us would have an impact on the author’s career. That should also answer your question about the “impact of publishing with CLR”–the impact we consider is the impact that publishing with a top ten law review would have on a new or less established scholar’s career, e.g., tenure or future publication prospects.We only have one cycle’s worth of data and even that is fairly limited because many authors chose not to provide additional information. Again, that choice has no bearing on whether and how we consider a piece. Our hope is ultimately to collect sufficient data to get a sense of what our submissions pool looks like. Anecdotal claims have been made by a variety of commentators about who actually submits law review articles. We hope that a fact-based inquiry into the demographics of our submissions pool will offer a more concrete answer to this issue.