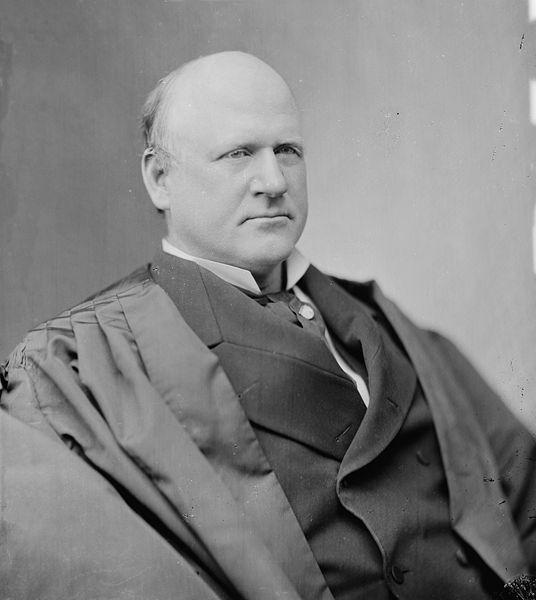

At the turn of the twentieth century, and while still sitting on the Supreme Court, Justice John Marshall Harlan I kept a side-job shaping the minds of young law students at Columbian University—a promising young institution in the nation’s capital, now known as the George Washington University. He primarily lectured in Constitutional Law, but also taught courses in personal property law, torts, conflict of laws, American jurisprudence, domestic relations, commercial law, evidence, and likely others. Today, however, only his constitutional law lecture notes remain.

Justice John Marshall Harlan

Offered every Saturday night between mid-October 1897 and early-May 1898, his course on constitutional law was attended primarily by evening students. This make-up reflected a more old-school approach (even by those standards) to the study of law than the popular methods pioneered by Christopher Columbus Langdell at Harvard, and which dominate the current legal academy. Harlan’s students, for the most part, maintained full-time jobs and paid annual tuition equivalent to what today’s law students might spend on an evening at the movies.

During the 1897–98 academic year, one of these students, George Johannes, transcribed Justice Harlan’s twenty-seven constitutional law lectures verbatim. Johannes had held onto these transcripts for more than a half-century when, in 1955, he passed them on to his former teacher’s grandson, John Marshall Harlan II, as he ascended the to the bench his grandfather knew so well. The papers were ultimately deposited in the Library of Congress, where they remain today in the library’s special collections.

This is the first in a series of blog posts, written in anticipation of our forthcoming article, in which we (myself and my co-author, Michael McCloskey) intend to provide glimpses of the countless gems contained in Justice Harlan’s lectures. We have carefully scanned and analyzed each of these pages at the Library of Congress. These papers reveal a great deal, not only about that time in our Constitution’s history, but also about the Justice as a man, and his at times uncanny ability to foreshadow constitutional developments unfolding even today.

Future topics will include the theory and practice of federalism, the common law’s proper role in federal courts, gender equality vis a vis the Equal Protection Clause, and an examination of Supreme Court justices and the practice of judicial statesmanship. For today, though, we begin with the gratuitously controversial, and hence timely issue of birthright citizenship.

When introducing any subject-area to his constitutional law students, Justice Harlan invariably preferred to begin with the text. It is thus in his honor that we begin the present discussion, by way of introduction, with reference to (and reverence for) the United States Constitution, which in pertinent part—i.e., the “Citizenship Clause”—reads:

All persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.

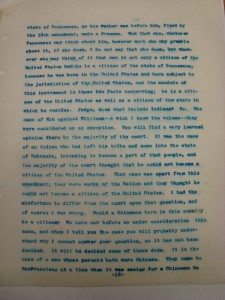

Wong Kim Ark

The Fourteenth Amendment was ratified less than three decades before Harlan taught it. In United States v. Wong Kim Ark, the Supreme Court considered whether birth in the United States was sufficient to grant United States citizenship. The Court, in a 6-2 decision by Justice Gray, held that Won Kim Ark, who was born in the United States to Chinese subjects, acquired citizenship at birth—this is the principle of jus soli. Chief Justice Fuller, joined by Justice Harlan, dissented. The dissent rejected this approach, and adopted the principle of jus sanguinis, whereby a child inherits citizenship from his or her father regardless of birthplace.

During Wong Kim Ark’s pendency before the Court, however, Columbian University’s Saturday evening constitutional law students were given a sneak-peak of the outcome of the case. On March 19, 1898, just nine days before the case was decided, Justice Harlan had just finished discussing the importance of Dred Scott in bringing about the end of slavery when he considered birthright citizenship for three classes of people—the son of a freedman, an Indian, and a “Chinaman.”

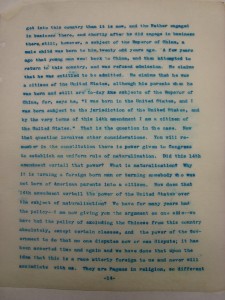

A child of “African descent” is born in Tennessee, Harlan hypothesized, and his “Father was before him, freed by the 13th amendment, [and] made a freeman.” Would the child be a citizen? “Now that man, whatever Tennessee may think about him, however much she may grumble about it, if she does . . . is not only a citizen of the United States but he is a citizen of the state of Tennessee, because he was born in the United States and born subject to the jurisdiction of the United States.

But “Judge,” Justice Harlan posing a question to himself interjects, “does that include Indians?” The answer: “No.” Harlan cited the “very learned opinion . . . by the majority of the Court in” Elk v. Wilkins, in which an Indian, born on a reservation, “left his tribe and came into the state of Nebraska, intending to become a part of that people.” The Court “thought that he could not become a citizen of the United States.” Harlan, who did not join that “learned opinion,” “had the misfortune to differ from the Court upon that question, and of course [he] was wrong.” Harlan would have found someone born on an Indian reservation to be a citizen of the United States.

But “Judge,” Justice Harlan posing a question to himself interjects, “does that include Indians?” The answer: “No.” Harlan cited the “very learned opinion . . . by the majority of the Court in” Elk v. Wilkins, in which an Indian, born on a reservation, “left his tribe and came into the state of Nebraska, intending to become a part of that people.” The Court “thought that he could not become a citizen of the United States.” Harlan, who did not join that “learned opinion,” “had the misfortune to differ from the Court upon that question, and of course [he] was wrong.” Harlan would have found someone born on an Indian reservation to be a citizen of the United States.

Next, Harlan asks, “Would a Chinaman born in this country be a citizen?” Referring to Wong Kim Ark, which would be decided a mere nine day later, Harlan cautions that the Court has “now before us under consideration this case, and when I tell you the case you will probably understand why I cannot answer your questions, as it has not been decided. It will be decided some of these days.” After these prefatory remarks about not being able to answer the question for the class because it had not yet been decided, he went on to frame the issue as whether the Citizenship Clause curtailed Congress’s power to establish a uniform rule of naturalization. Harlan described the facts of the case, wherein in “a subject of the Emperor of China . . . [gave birth to] a male child.” Wong Kim Ark, the son, now claims citizenship of the United States, “although his parents when he was born and still are today the subjects of the Emperor of China.”

Harlan asked whether the 14th Amendment curtailed “Congress’ [power] to establish a uniform rule of naturalization”? Harlan answers, “giving the argument on one side,” which coincidentally happens to be the view he adopted in dissent. “We have for many years had the policy . . . of excluding the Chinese from this country, absolutely, except certain classes, and the power of the Government to do that no one disputes now or can dispute.” Harlan suggests that these actions are against “a race utterly foreign to us and [that] never will assimilate with us. They are Pagans in religion, so different from us that they do not inter-marry with us, and we don’t want to inter-marry with them, no matter how long they have been here, they make arrangements to be sent back to their Fatherland.” “Thus there is a wide gulf between our civilization and their civilization, and we don’t want to mix.”

Harlan asked whether the 14th Amendment curtailed “Congress’ [power] to establish a uniform rule of naturalization”? Harlan answers, “giving the argument on one side,” which coincidentally happens to be the view he adopted in dissent. “We have for many years had the policy . . . of excluding the Chinese from this country, absolutely, except certain classes, and the power of the Government to do that no one disputes now or can dispute.” Harlan suggests that these actions are against “a race utterly foreign to us and [that] never will assimilate with us. They are Pagans in religion, so different from us that they do not inter-marry with us, and we don’t want to inter-marry with them, no matter how long they have been here, they make arrangements to be sent back to their Fatherland.” “Thus there is a wide gulf between our civilization and their civilization, and we don’t want to mix.”

Harlan poses a series of hypotheticals of what “would have been the condition today of the states of California, Oregon, Washington, Nevada, and Utah . . . if we had no restrictions whatever against the admission of Chinese in this country.” Fearing that if “fifty million” of the “two or three hundred million” in China immigrated to the “Pacific slope” with no restrictions, these states “would have been dominated by that race; they would have rooted out the American population that is there; would have compelled all of the laboring part of that country to have left and come to other parts of the country to seek subsistence.”

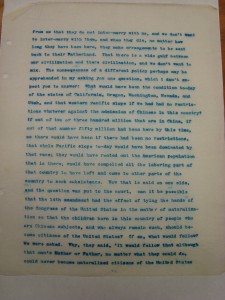

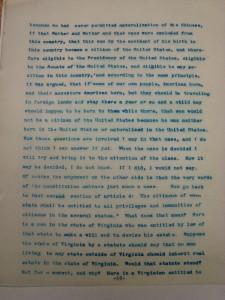

Harlan queries, as “the question was put to the Court, can it be possible that the 14th Amendment had the effect of tying the hands of the Congress of the United States in the matter of naturalization so that the children born in this country of people who are Chinese subjects, and who always remain such, should become citizens of the United States.” Harlan fears a scenario wherein a “Father and Mother [of a] race [that was] excluded from this country . . . [had] a son by the accident of his birth in this country” who would be “eligible to the Presidency of the United States.” By “the same principles . . . if some of our own people, American born, and their ancestors American born . . . [should give birth to a child] while . . . traveling in foreign lands . . . that son would not be a citizen of the United States because he was neither born in the United States or naturalized in the United States.” Notwithstanding his excessive commentary on the issue, Harlan notes that he “do[es] not think [he] can answer [the questions] yet.” When “the case is decided I will try and bring it to the attention of this class. How it may be decided, I do not know. If I did, I would not say.” After this lengthy oration on the arguments against birthright citizenship, Harlan pithily summarizes the “argument on the other side [with but a single sentence—] . . . that the very words of the constitution embrace such a case.”

Harlan queries, as “the question was put to the Court, can it be possible that the 14th Amendment had the effect of tying the hands of the Congress of the United States in the matter of naturalization so that the children born in this country of people who are Chinese subjects, and who always remain such, should become citizens of the United States.” Harlan fears a scenario wherein a “Father and Mother [of a] race [that was] excluded from this country . . . [had] a son by the accident of his birth in this country” who would be “eligible to the Presidency of the United States.” By “the same principles . . . if some of our own people, American born, and their ancestors American born . . . [should give birth to a child] while . . . traveling in foreign lands . . . that son would not be a citizen of the United States because he was neither born in the United States or naturalized in the United States.” Notwithstanding his excessive commentary on the issue, Harlan notes that he “do[es] not think [he] can answer [the questions] yet.” When “the case is decided I will try and bring it to the attention of this class. How it may be decided, I do not know. If I did, I would not say.” After this lengthy oration on the arguments against birthright citizenship, Harlan pithily summarizes the “argument on the other side [with but a single sentence—] . . . that the very words of the constitution embrace such a case.”

Justice Harlan more than tipped his hand as to how he thought the case was to be decided. Chief Justice Fuller’s dissent, which Harlan had joined, argued that a “Chinaman” born in the United States to parents who were still subjects of China could not become a citizen. Many of the Chief Justice’s arguments track closely with the xenophobic argument Harlan had presented to the class. Primarily, that the 14th Amendment codifies the rule of jus sanguinis, whereby a child inherits citizenship from his or father regardless of birthplace.

Both Harlan’s lectures and Fuller’s opinion note the unwillingness of Chinese immigrants to assimilate and their continued loyalty to the Emperor of China. Both also make the exact same comment that the framers could not have intended a foreigner born by accident in the United States to be eligible to run for President, while children of American citizens born abroad were not: “Considering the circumstances surrounding the framing of the constitution, I submit that it is unreasonable to conclude that ‘natural born citizen’ applied to everybody born within the geographical tract known as the United States, irrespective of circumstances; and that the children of foreigners, happening to be born to them while passing through the country, whether of royal parentage or not, or whether of the Mongolian, Malay, or other race, were eligible to the presidency, while children of our citizens, born abroad, were not.” It is rather clear that Justice Harlan held these beliefs deeply—in class he vigorously argued in favor of his position, but only casually mentioned the other side’s argument in a single sentence.

Both Harlan’s lectures and Fuller’s opinion note the unwillingness of Chinese immigrants to assimilate and their continued loyalty to the Emperor of China. Both also make the exact same comment that the framers could not have intended a foreigner born by accident in the United States to be eligible to run for President, while children of American citizens born abroad were not: “Considering the circumstances surrounding the framing of the constitution, I submit that it is unreasonable to conclude that ‘natural born citizen’ applied to everybody born within the geographical tract known as the United States, irrespective of circumstances; and that the children of foreigners, happening to be born to them while passing through the country, whether of royal parentage or not, or whether of the Mongolian, Malay, or other race, were eligible to the presidency, while children of our citizens, born abroad, were not.” It is rather clear that Justice Harlan held these beliefs deeply—in class he vigorously argued in favor of his position, but only casually mentioned the other side’s argument in a single sentence.

Harlan returns to Wong Kim Ark on May 7, 1898, the last class of the term. He remarked that “[w]e had an illustration of the application of [the Fourteenth] amendment.” The “question turns upon two or three words of this amendment”—actually five word—“subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” At no point during the March 19, 1898, lecture did Harlan ever mention those words. If Wong Kim Ark “was within the meaning of that clause, subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, then he became a citizen of the United States, and of the state wherein he resided.” “The majority of the Court held that he was.” “The minority,” which Harlan joined, “held that he was not born [subject] to the jurisdiction of the United States.” With his trademark wit, Harlan declared, “I was one of the minority, and of course I was wrong.”

Harlan explained his reasoning, observing that “he was not born subject to the political jurisdiction of the United States, of course he owed no allegiance to our laws, as every man who comes here, but he was born under the jurisdiction of the United States, within the meaning of this Article of the Constitution.” This mirrors the statement of Senator Trumbull during the ratification debates of the Fourteenth Amendment, cited in the Wong Kim Ark dissent, that “What do we mean by ‘subject to the jurisdiction of the United States’? Not owing allegiance to anybody else; that is what it means.’”

Harlan revisits the example he posed in his earlier class, that was discussed in Wong Kim Ark, wherein an “English father and mother went down to Hot Springs [in Arkansas] to get rid of the gout . . . and while [they were] there, there is a child born.” The boy goes back to England. “Is this child a citizen of the United States, born to the jurisdiction thereof, by the mere accident of his birth?” Harlan answers no. His reasoning is more expansive, no longer focusing on his xenophobic views of the Chinese, but more broadly denying birthright citizenship to anyone subject to the loyalty of any foreign power. “My belief was [that the Fourteenth Amendment] was never intended to embrace everybody in our citizenship if he was the child or parents, who can not under the law become naturalized in the United States.” While Congress can grant citizenship to the parents of natural born citizens, Harlan was unable to believe that “when the boy’s parents could not become citizens of the United States [through the Constitution, or laws of Congress at that time], that it was possible for the [boy] to become a citizen of the United States.” Closing with charm, Harlan whims that “of course I am wrong, because only the Chief Justice, and myself, held those views, and as the majority decided the other way, we must believe that we were wrong.”

It is curious that Justice Harlan had such a narrow conception of citizenship for Chinese immigrants based on his broad view of rights and citizenship for freed slaves. On May 17, 1898, he commented that “every negro in the United States, if he had been born there, or has been naturalized in the United States, when th[e 14th amendment] was adopted, became a citizen of the United States, and of the state wherein he resided.” Likewise, he remarked on May 7, 1898 that “if there is a black man who can get ahead of me, I will help him along, and rejoice, and his progress in life does not excite my envy, and I am glad to feel and know that it is the desire of the white people in this country, that the race shall push themselves forward in the race of this life.” But it seems that he viewed the Civil Rights amendments to solely benefit freed slaves, and not Chinese aliens.

-Co-authored by Josh Blackman and Michael McCloskey.