A common analysis of Chief Justice Roberts is that he is playing the “long game.” There are two variants of this claim–the short long game, and the long long game.

The easiest example of the short long game is what Richard Re has called the Doctrine of One Last Chance–the Chief Justice fires a warning shot across the bow before he invalidate a law. For example, Northwest Austin warned the Congress to fix the Voting Rights Act–they didn’t, and a few years later part of it was invalidated in Shelby County v. Holder. But even then, other parts remain–perhaps still on the chopping block. As Rick Hasen noted at the time, “The chief justice is a patient man playing a long game. He was content to wait four years to strike down a key provision of the Voting Rights Act. Apparently he likes to say I told you so.” Four years is about the upper limits of the short long game. Fisher II may be an example of this approach, but at worst, the Court tells the 5th Circuit they didn’t listen to Fisher I, so I don’t know if that quite counts.

The long long game occurs over a far greater time horizon. Perhaps the most commonly cited example goes like this–the Chief Justice upheld the Affordable Care Act to save the institutional credit of the Supreme Court to make it more tolerable to invalidate something else. For example, in June 2012 (after NFIB was decided), David Franklin wrote in Slate “A cynic might say that Roberts is keeping his powder dry for impending battles that are closer to his heart, such as the constitutionality of affirmative action. But I think Roberts is playing the long game.” Adam Liptak made a similar point, noting: “I think he’s an exceptionally smart, patient tactician who is playing a long game. He’s a young man by Supreme Court standards. He’s only 58. He’s going to be there for decades. And in incremental ways, he’s planting seeds in current decisions that will take root and allow him to move the Court in his preferred direction over time.” In Bloomberg, Paul Barrett wrote: “The chief justice’s majority opinion in last term’s Obamacare case revealed not a conservative-gone-wobbly, but a sophisticated steward of the court’s status as an independent institution. Roberts, 60, occasionally steps back from the ideological barricades, not for lack of spine but because he’s playing a savvy long game.”

The short long game makes sense only in a hypothetical world. No one expected the Congress to revise the Voting Rights Act in response to Northwest Austin. The Chief’s gentle nudge fell somewhere between faux humility and an empty gesture.

The long long game, however, suffers from a much deeper problem. The notion that a single Chief Justice can single-handedly shape the law over the course of decades, as if he were moving pieces around on a three-dimensional chess set, suffers from what F.A. Hayek referred to as the “fatal conceit.” Our society as a whole is infinitely more complex than any one person could ever possibly understand. It is the “fatal conceit” of central planners that they presuppose enough knowledge to control all aspects of human existence. The notion that Roberts can forge a thirty-year plan—-Stalin only tried for 5 years–to transform the law crumbles on inspection.

The Supreme Court does not exist in a vacuum, where a stasis is maintained. Everything changes. First, and most obviously, the composition of the Court changes. Even if the Chief Justice has a broad vision of what he wants to accomplish, if President Clinton appoints three Justices, all of those plans vanish instantly. His first decade of planning and calculating will be for naught, and the Chief Justice will be in dissent for a generation. Even if a Republican President appoints two or three Justices, there is no way for Roberts to know how they’ll vote. Maybe those Justices will also have a master plan, and will not agree with the Chief’s plan. Or maybe (hopefully not) we will get another Souter or Stevens.

Second, beyond the composition of the Court, the Chief needs to deal with unpredictable actions from the other branches. It is impossible to know what sort of cases will make their way to the Court’s docket. As Randy and I noted in our Weekly Standard piece, no one (not even the Chief) can anticipate the constitutional black swans that will emerge in the future.

If you had been told in 2008 that the Supreme Court would soon be called upon to decide whether Congress could compel millions of Americans to buy health insurance, you would have chuckled. If you had been told in 2000 that the Supreme Court would hear a series of cases over the next decade deciding whether the president had the power to detain suspected terrorists in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, you would have laughed. If you had been told two years earlier that a disputed presidential election in Florida would be appealed to the Supreme Court, you wouldn’t have believed it.

Ruling a certain way in some cases, in the hopes that you can rule differently in others, totally mistakes that a third category of unforeseen cases will alter that calculus. Maybe the Chief Justice decides to uphold Obamacare so he can invalidate affirmative action (assuming everything else is equal), but what happens when the Court is called on to decide whether the President’s use of executive action to enter the United States into a binding climate “treaty” is valid. Or if a Russian company, that does business in Syria and the United States, sues in a federal court when an American-backed rebel group blows up its airfield. Or if an FDR wannabe decides to pack the Court, and force the oldest Justices into “Senior” status, where they cannot hear cases. I could go on and make up cases, but the simple fact is, horse trading one conservative decision for another liberal decision wreaks of an omniscience based on ceteris paribus (all things remain equal).

Third, it also assumes that public opinion of the Court remains static. Maybe the Chief Justice did vote the way he did in NFIB to avoid the Court becoming an issue during the 2012 election. (I write about this in Unprecedented). Maybe he hoped that there would be a temporary blip in the Court’s unpopularity, but conservatives would come around. Attempting to forecast public opinion is a foolhardy errand–just ask Hillary Clinton and Jeb Bush right now–and in the four years since NFIB, we still haven’t seen such a turnaround. Recent numbers from Gallup show:

Half of Americans (50%) disapprove of the job the U.S. Supreme Court is doing, while slightly fewer (45%) approve. Although the high court’s approval rating is similar to what it has been in recent years, the current disapproval rating is at a new high

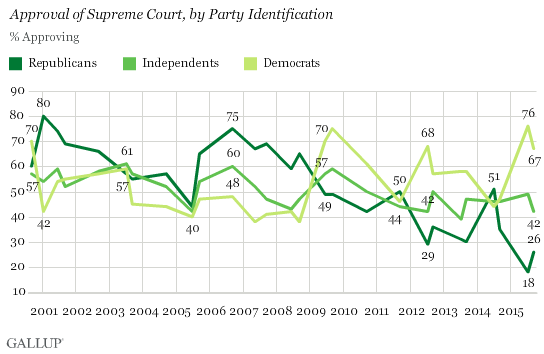

Republicans and Democrats are trending downwards in their favorability of the Court:

But maybe after this upcoming “Conservative” term, the numbers will be different? Well that depends (as always) on what Justice Kennedy does. Any prediction of a conservative resurgence is unpredictable.

If there is a Justice on the Court playing the long game, it is Justice Thomas. His dissents frequently raise issues that people had not considered before. These dissents start discussions, scholarly debate, and plant the seeds to alter cases many years in the future. His writings on the administrative state last year I think augur a serious shift in our law. His McDonald opinion on the privileges or immunities clause cannot be disregarded. Thomas’s commitment to exploring the original meaning of various provisions of the Constitution have the greatest potential to shape our Supreme Court jurisprudence in decades. Frameworks like originalism or textualism make an impact on the court over the long haul–not trying to horse trade a liberal case for a conservative case.