Last to cast his vote at the conference was the most pivotal vote: Chief Justice Roberts. What Roberts would say at this pivotal moment remains one of the most hotly contested rumors in Washington history.

On July 1, 2012, days after the Supreme Court decided NFIB v. Sebelius, Jan Crawford released a bombshell story. She reported that at the conference, Chief Justice Roberts “initially sided with the Supreme Court’s four conservative justices to strike down the heart of President Obama’s health care reform law.” At the conference, “Roberts agreed” that Congress did not have the commerce clause power to enact the mandate, and “aligned with the four conservatives” to find the mandate unconstitutional on commerce clause grounds. Crawford reported that the Chief was “less clear on whether . . . the rest of the law must fall.” Other issues, such as the issue of “severability and the Medicaid expansion ”were still in play.”

Because Roberts was the most senior Justice in the majority opinion, Crawford reported that “he got to choose which justice would write the court’s historic decision. He kept it for himself.”

One of the greatest mysteries in washington, is where did the leak come from?

To understand the source of the leak, we must turn back time to the Supreme Court’s October 1980 term. Fresh from his clerkship with Judge Henry Friendly, a young, baby-faced John Glover Roberts, Jr. arrived in the chambers of Justice William H. Rehnquist. It was a tumultuous time at the Court. The year before, Bob Woodward and Scott Armstrong released the controversial book, The Brethren, that provided an insiders look at the Supreme Court, including detail of some of the most controversial decision of the Burger Court. It has been reported that Justices Stewart, Powell, and Blackmun had leaked to Woodward and Armstrong, though the other leakers remain unknown. Also in 1979, Tim O’Brien of ABC News received a leaked report from the Court about the authorship and outcome of two pending cases. The leak was blamed on a typist at the Court, who was promptly fired by the Chief, after what the AP called a “confrontation in Burger’s chambers.” By the start of the 1980 Term, Burger was enraged that his Court had turned into a sieve. However, keeping with his weak managerial style, he did nothing to stop it. Internally, the other Justices scoffed at his poor leadership.

Rehnquist was even more furious at Burger for his failure to do anything about the leaks. The future Chief Justice shared his frustration with his star law clerk, Roberts, also a future-Chief. Rehnquist decided to do something about this problem, and asked Roberts to prepare a document that would become known as the “Confidentiality Resolution.” The resolution, which Rehnquist sought to have all nine Justices sign, would require that each member of the Court pledge not to leak any information. It would seem that such a pledge was unnecessary, but after The Brethren, Rehnquist, with his usual blunt style, determined that this may be the only way to force the issue into the open. Any Justice who refused to sign the pledge would be singled out as a potential leaker. Rehnquist thought the peer pressure could put a tourniquet on the leaks. Roberts prepared the resolution, and Rehnquist sent it to Burget to present at the next conference. However, Burger’s efforts to persuade his colleagues to sign the resolution at the conference failed miserably. In his memoir Five Chiefs, Justice Stevens wrote of the Chief, “Burger was not, however, equally proficient as a presiding officer at our conferences.”

After this defeat, Rehnquist was even disappointed in Burger. Roberts learned that the resolution was not adopted, and became annoyed at Burger. Roberts would understand from a very early age the significance of leaks from inside the Court. He would re-learn this lesson the hard way two decades later.

Fast-forward to June 15, 1986, the final days of Chief Justice Burger’s term. Once again, Tim O’Brien published a leak that the Supreme Court would strike down the Gramm-Rudman budget balancing law in Bowser v. Synar. Rehnquist was enraged that there was another leak from the Court, again to O’Brien. Once again, the leak was blamed on someone in the printing office, but Rehnquist suspected otherwise. Five days later, President Reagan nominated Rehnquist to replace Burger as Chief Justice. Rehnquist who was confirmed, and sworn in on September 26, 1986, knew what one of the first orders of business would be.

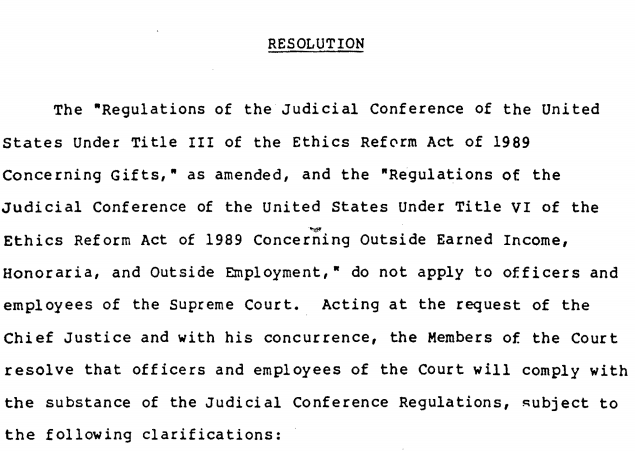

Over his years as Chief, at various points, Rehnquist would ask all of Justices to agree to “resolutions” to control internal governance matters at the Court. These resolutions were kept private. For example, on January 18, 1991, Rehnquist signed what became known internally in the Court as the “Ethics Resolution.” The resolution stated in part, “Acting at the request of the Chief Justice and with his concurrence, the Members of the Court resolve that officers and employees of the Court will comply with the substance of the Judicial Conference Regulations.” The resolution was signed by Rehnquist.

Fittingly, this resolution was released by Chief Justice Roberts in February of 2012 to Senator Leahy after calls for recusals of both Justices Thomas and Kagan in the imminent health care case. Only two months later, on May 14, Senator Leahy gave a speech on the Senate floor pointed right at Chief Justice Roberts. “I trust that he will be a Chief Justice for all of us and that he has a strong institutional sense of the proper role of the judicial branch,” said Leahy. “The conservative activism of recent years has not been good for the court. Given the ideological challenge to the Affordable Care Act and the extensive, supportive precedent, it would be extraordinary for the Supreme Court not to defer to Congress in this matter that so clearly affects interstate commerce.”

Towards the start of the October 1986 term, Rehnquist dusted off Roberts’ “Confidentiality Resolution,” and handed a copy to each Justice at the so-called “Long Conference.” By that point, the composition of the Court had changed somewhat. Burger and Stewart were out. Scalia and O’Connor were in. And a new Chief was in charge.

Rehnquist, who was known for a strong leadership style at conference, insisted that the justices all concur to this resolution. Like the 1991 memo, it was initiated at the “request of the Chief Justice,” but was approved “with his concurrence” and that of the “Members of the Court.” The memo was unchanged from Roberts’ draft years earlier. It stated, quite simply, that everyone who worked at the Court would “not release any confidential information about the Supreme Court.”

All of the Justices, not wanting to upset the new Chief on his first day, went along with it. Yet, several of the Justices had their doubts. It wasn’t that they thought it was appropriate to release confidential information to the press, but rather they deemed it unwise to rule it out in all circumstances. Perhaps the scenario would emerge one day where it would be necessary for the sake of the Court’s legitimacy to make the deliberations known. Coming off of the difficult times of the Burger Court, and uncertain how Rehnquist would preside–he was already twisting arms over the “Confidentiality Resolution”–a few of the Justices signed it with reservations. One long-time Justice may have signed it, but, not keeping with his jurisprudence, did not defer to it. After it was signed, Rehnquist told his former clerk, John Roberts–who at this time had already left the White House and entered private practice–that his old draft had come in handy. Roberts was pleased.

The resolution, though well-intentioned, was not foolproof. Over the next fifteen years, people at the Court talked to reporters about cases already decided. However, there were no leaks about pending cases. Rehnquist, though not pleased with books from Crawford and Jeffrey Toobin and others, was relieved that the deliberations of pending cases remained within the Court. But he was furious with the immediate release of Justice Marshall’s papers. As Professor Ross Davies noted, Rehnquist was “hostile toward Thurgood Marshall’s plan.” In contrast, Rehnquist’s “case files will not be released in full until after the deaths of all the justices with whom he served on the Court.”

Fast-forward to 2005. On July 19, 2005 John G. Roberts was nominated to replace the retiring Justice O’Connor. Rehnquist, who at this time was already quite ill, called Roberts and O’Connor for a private meeting at his home in Virginia. At the get-together, among other matters, the “Confidentiality Resolution” was discussed. O’Connor, recognizing that her time on the Court was short, renewed some of her skepticism about the resolution, but told Roberts that he should ensure that the other Justices adhered to the policy. She had learned her lesson well after her ill-timed remarks on the night of the 2000 Presidential election, when she said she would be reluctant to retire if a Democrat were President. Rehnquist passed away on September 3, 2005, and President George W. Bush then nominated Roberts as the Chief.

Fast-forward to May of 2012. The deliberations for NFIB v. Sebelius from the Supreme Court were leaked, and many in Washington acted on those leaks. Several reporters wrote about possible leaks at the time, but it wasn’t until Crawford’s report in July that the story was solidified. On June 25, 2012, days before NFIB v. Sebelius is decided. Supreme Court veteran reporter Joan Biskupic reported on the imminent decision, and queried whether anyone knew what would happen. Biskupic, who spoke with O’Connor, wrote that if she “knows what her erstwhile colleagues are deciding on that case, she isn’t talking.” When asked, O’Connor told her former biographer, “I haven’t a clue.”

Indeed, O’Connor had no clue what the Court would decide–but she knew out who did. Who is it? Our first female Justice has left us an invaluable clue in unraveling this enigma in the last place anyone who follows the Court would ever check.

Indeed, O’Connor had no clue what the Court would decide–but she knew out who did. Who is it? Our first female Justice has left us an invaluable clue in unraveling this enigma in the last place anyone who follows the Court would ever check.

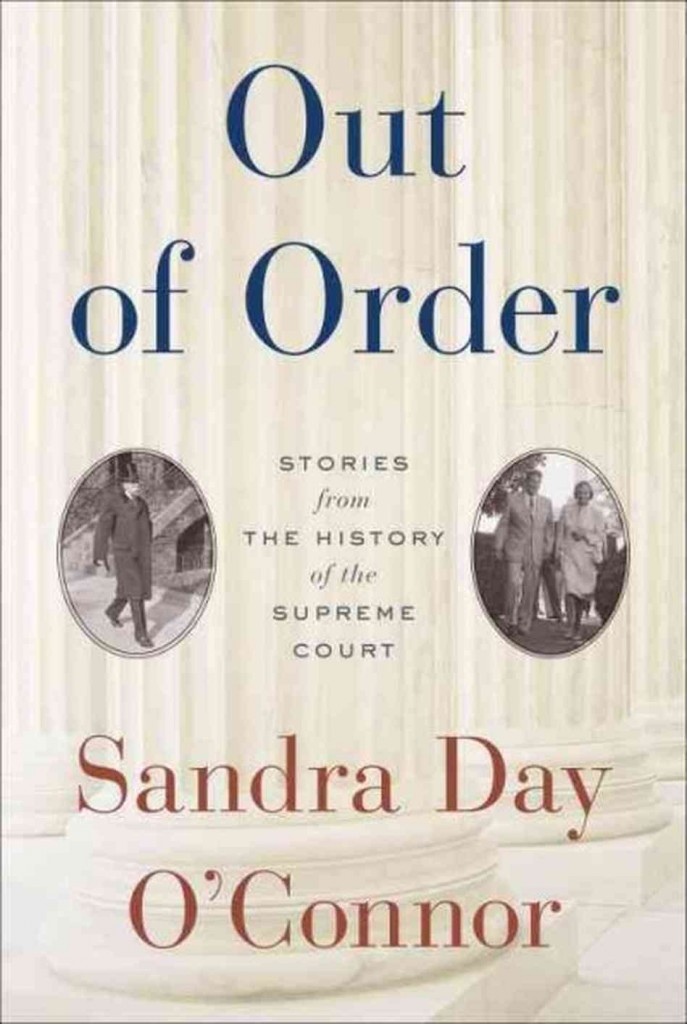

In his review of Justice O’Connor’s new book, “Out of Order,” Adam Liptak criticizes it for being devoid of substance. Brutally, Liptak adds “The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution are included in an appendix. They are surely worth rereading from time to time, but their main purpose here seems to be to add some bulk to a very skimpy effort.” This criticism is off the mark. Liptak underestimates the majesty of O’Connor’s law.

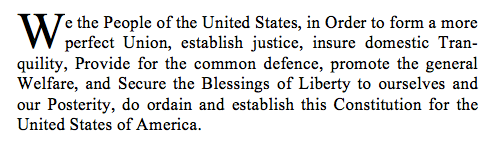

Indeed, there is something unique about this Constitution, that only the closest of inspections could ever reveal. Look at the Preamble from O’Connor’s book carefully (p. 173).

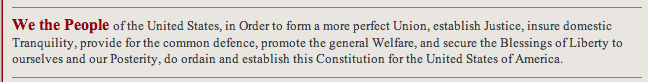

Though rules of capitalization were often unsettled at the time of our founding, the Preamble to the Constitution has a canonical typography. Here is the Preamble of the Constitution at the National Archives.

Now consider the official transcript courtesy of the National Archives:

Do you see any differences between O’Connor’s preamble and the preamble from the National Archives? Without any explanation, you will see three slight alterations in the capitalization of words. After the perfect union is formed, the first, third, and fifth clauses are modified. The word “Justice,” capitalized in the Constitution, is not capitalized here. The words “provide” and “secure,” which are not capitalized in the Constitution, are capitalized here. These changes were not inadvertent.

For you see, the answer to this Unprecedented Supreme Court leak is out of order. That is, the very substance of the Constitution that the Court is here to protect, is out of order.

The source of the leak is right where we should always look–in the Constitution.