The 20th Amendment provides that the President’s Term of Office ends on January 20, 2013 (though it doesn’t really say when it must begin). But what happens when the 20th falls on a Sunday, when an inauguration is impractical (or immoral, take your pick)?

Such is the case this year. As a precaution (overly abundant in light of what happened in 2009), the Chief Justice will administer the oath to the President on Sunday, January 20, prior to the actual inauguration on January 21.

Of course, what would happen if the President, perhaps due to religious convictions, refused to take the oath on a Sunday. Well it happened before, perhaps. Outgoing President James Polk’s term ended on Sunday, March 4, 1849. His successor, Zachary Taylor, refused to be sworn in on a Sunday. Same for incoming VP Millard Filmore.

So who was the President on Sunday, March 4, 1849?

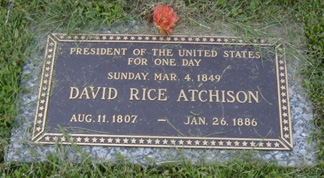

Under the Presidential Succession statute at the time (the Presidential Succession Act of 1792), after the Vice President, the Senatore Pro Tempore was in line. Under this theory, Senator David Atchison of Missouri would have been the President for the Day. However, Atchinson, was the President Pro Temp during the Thirtieth Congress. This position expired when that Congress adjourned on March 4.

Athcinson was in fact sworn in as President Pro Tempore on Monday before either Taylor or Dallas took the oath, so in theory, he was President for a few minutes.

Alas, no one actually considers Atchinson to have been President. Except for his tombstone.

In any event, how did Atchinson spend his day as Commander in Chief? He told the St. Louis Globe-Democrat,”There had been three or four busy nights finishing up the work of the Senate, and I slept most of that Sunday.”

Indeed, because of Justice Sotomayor’s important book signing, Biden will be taking the Oath of the Presidency hours before Obama. Thus, between 8:00 a.m. and noon, Biden will be President. In fact, there would be a President Joe Biden, and two Vice Presidents Joe Biden. Well played Sotomayor, well Played.

Oh, and while I am on the topic, for those who say the Constitution makes no references to religion, please point them to Article I, Section 7.

If any Bill shall not be returned by the President within ten Days (Sundays excepted) after it shall have been presented to him, the Same shall be a Law, in like Manner as if he had signed it, unless the Congress by their Adjournment prevent its Return, in which Case it shall not be a Law.

Yes. The Constitution specifically countenances that a President, who observes the Sabbath on Sunday, should not be penalized for failing to return a bill. Alas, a Jewish President would be a day late and a dollar short. However, the 20th Amendment contains no exception for Sunday, so we are stuck here.

Also, Tim Sandefur raises an interesting bit of trivia:

Pres. Obama will be the only president other than FDR to be sworn in four times. He was sworn in twice because of the mistake last time around, and because Inauguration Day falls on a Sunday this year, he’ll be sworn in on Sunday and then again at the ceremony Monday.

Let’s hope the Chief gets it right. Though, as Adam Liptak reports, When asked about the Chief Justice Administering the oath of office, which he had notoriously flubbed in 2008, Robert Gibbs,Obama’s press secretary, said “Given health care. I don’t care if he speaks in tongues.”

Update: Will Baude points me to a great article by Jaynie Randall, titled “Sundays Excepted.”

This Essay offers a historical account of the Sunday exception and argues that rather than endorsing religious observance, the Sunday exception reflects two related principles: a deliberation principle and a federalism principle. First, the Framers afforded the President a ten-day period (Sundays excepted) for the consideration of bills; this was a longer period than those contained in the two state constitutions which granted an executive veto in 1787. 16 The ten-day period reflects the Framer’s conception of a deliberative President, one who relied on advisors and collaborated with Congress in wielding his negative. Second, the Sunday exception reflects the fact that each of the thirteen colonies had Sunday laws (commonly called Blue Laws) 17 of various types at the time of the Constitutional Convention. 18 Many of these statutes prohibited labor and travel on Sundays. 19 Thus, in order for the President to deliberate and to call upon the aid of his advisors without violating these laws, the Constitution needed an exception from the brief period allowed for executive deliberation.

Fascinating. Jay Wexler wrote about it on the Odd Clauses blog:

Of course, some have suggested that this provision supports the view that the Framers thought we were a Christian nation. According to this argument, the framers wrote the parenthetical into the Constitution as a way of recognizing that Sunday is the true sabbath and day of rest that god wants us to observe every week and so on and so on. On the other hand, there’s this awesome article from the Alabama Law Review, written by 2006 Yale Law grad and (it would seem) former clerk to Justice Alito, Jaynie Randall (now Jaynie R. Lilley), which argues against the Christian enshrinement thesis and suggests instead that federalist concerns (many states had so-called Blue Laws that prohibited travel and labor on Sundays, and the framers didn’t want to interfere with them) best explain the clause.

Really cool. Will was among those thanked in the dagge rnote (and some guy named Akhil).

You know, I used to cite the fact that the Constitution uses the words “in the year of our lord” as proof of another reference to religion in the Constitution, but that guy named Akhil said that’s wrong.

Yale is totally dumping on the Christian Constitution 🙂

Update 2: Cool, I made the Front Page of Digg.com.

I corrected a few nits pointed out in the comments. My apologies, I wrote this post quite late last night. Also, it seems that there have been several Sunday swearing-ins: Ronald Reagan in 1985, Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1957, and Woodrow Wilson in 1917. Rutherford B. Hayes took the oath on a Saturday in 1877, the public inauguration was on Monday.

Perhaps most interesting is James Monroe. According to the official Senate.gov site:

Monroe’s Inauguration was the first inauguration to fall on a Sunday. Monroe decided to hold the Inaugural ceremony on Monday, March 5, after consulting with Supreme Court justices.

Of course, the Chief Justice at the time was John Marshall.

Update 3 (1/21/12): Thanks to the link from Digg, yesterday was my most trafficked day with over 11,000 visits! Akhil Amar writes in with this update about why Atchison was never actually President.

In addition to the argument and evidence presented in my fn 14, I do not believe there is any evidence Atchison himself ever took the specific presidential oath of office prescribed by Article II. So any claim that Zach Taylor somehow wasn’t president prior to taking the oath would seem self-defeating for Mr. A and his allies: Mr. A didn’t take this oath either.

Amar writes in FN 14 of Chapter 9 of his new book, America’s Unwritten Constitution:

As for the Obama oath re-do in 2009, here are the key points to keep in mind: A new president-elect receives his official designation— his commission-equivalent— from Congress as a whole, which bears responsibility for counting electoral votes, resolving any disputes (such as those which arose in 1876– 1877), and, if necessary, choosing among the top electoral-vote-getters (if no candidate has enough electoral votes to prevail, as occurred in 1824– 1825). The president-elect, by dint of the explicit command of the Twentieth Amendment, legally becomes president at the precise stroke of noon on January 20. The clock and not the oath does the work. In this explicit text, we see on display the perfect seamlessness and continuity of the American presidency, which, unlike courts and Congress, never goes out of session— an obvious carryover from the seamlessness of the British system (“ The [old] king is dead; long live the [new] king!”). Textually, it is clear from the words of Article II that the oath is a duty imposed on the person who is already president, not a magic spell that makes him president: “Before he [the president] shall enter on the Execution of his Office, he shall take the following Oath or Affirmation.…” In Britain, it was not uncommon for months or even years to elapse between the start of a monarch’s official reign and the taking of the official Coronation Oath with all its pomp and ceremony. Prior to the ratification of the Twentieth Amendment, which contains the word “noon,” a nice question had arisen about whether the magic moment of presidential transition was midnight or noon (or some other instant). The original text did not specify an hour, but early unwritten practice identified midnight as the magic moment. Hence the storied efforts of John Adams and his staff to sign and seal judicial commissions late into the evening of his final hours on the job in an effort to vest his “midnight judges” with the proper authority.