I recently saw the new movie Loving, which was based on Loving v. Virginia. I have no qualifications to opine on the quality or acting of the film, but I can discuss its constitutional faithfulness. (See my previous review of Woman in Gold).

In a very dramatic scene, the police opened the Loving’s unlocked door, and barged into their bedroom in the dark of night. (I could not figure out if they had a warrant, though I doubt it mattered). Loving pointed to their marriage license, procured in the District of Columbia. The police replied that the license was not valid in Virginia. The New York Times offered this account in Mildred Loving’s obituary:

By their own widely reported accounts, Mrs. Loving and her husband, Richard, were in bed in their modest house in Central Point in the early morning of July 11, 1958, five weeks after their wedding, when the county sheriff and two deputies, acting on an anonymous tip, burst into their bedroom and shined flashlights in their eyes. A threatening voice demanded, “Who is this woman you’re sleeping with?” Mrs. Loving answered, “I’m his wife.” Mr. Loving pointed to the couple’s marriage certificate hung on the bedroom wall. The sheriff responded, “That’s no good here.”

Both were transported to the county jail in separate cars. Richard Loving made bail on Friday morning, but Mildred (I suspect deliberately) was held the entire weekend till the Judge appeared on Monday. Richard tried to bail out his wife–who at that point was several months pregnant–but the clerk insisted he wait until Monday. The Sheriff told Richard that if he tried to bail out Mildred again, he’d be arrested. The sheriff said that Mildred’s family members should come to bail her out.

Eventually, both were released. In a later scene, they appear in a lawyer’s office. The attorney told them that he was friends with the judge, and worked out a deal: there would be a one-year suspended sentence, but they could not cohabitate together in Virginia. There was a moment of silence, as they considered their options. But it was only a moment, and they agreed. In the next scene, the judge asked for their pleas, and they both replied–meekly–“guilty.”

Shortly thereafter, both Richard and Mildred moved to the District of Columbia. However, Mildred wanted to give birth in her hometown. (In the film Richard’s mother was a midwife). So they drove back to Caroline County, Virginia (near Fredericksburg). The morning after the baby was born, the police showed up and arrested the couple. The judge was about to sentence them to jail time, but their attorney barged into court, out of breath. The attorney told the judge that he had explained they could return to give birth to their child. Somewhat implausibly, the judge accepted this proffer, and allowed them to leave the Commonwealth without any punishment. (I couldn’t find any evidence of this return visit to Virginia).

Years later, while watching the March on Washington on television, a relative tells Mildred to write Bobby Kennedy about her situation. She does that. Out of the blue, attorney Bernard S. Cohen calls the Loving residence. He identifies himself as a founding member of the ACLU’s Virginia Chapter, and says Attorney General Kennedy referred the case. Mildred said she could not afford an attorney. Cohen explains the ACLU would pay all fees. Mildred’s face lights up. First Cohen asks them to meet at his office in Alexandria. That would create a problem. Instead, he says they can meet at his D.C. office. He does not actually have a D.C. office. In a funny scene, he (apparently) borrows a colleagues office. He walks in, takes down all of the photographs of the other lawyer’s family, and swaps out his nameplate.

The meeting with the attorney was even funnier. Cohen explains that it was too late to appeal the suspended sentence (statute of limitation was 60 days), so he suggests that the Lovings go back to Virginia to get arrested. That way they could appeal the sentence, and take it all the way to the Supreme Court. This is the sort of idiotic advice a 1L would think of to get around a statute of limitation. Richard Loving looked at the lawyer and said he was not going back to jail. They leave.

Cohen, who (in the movie at least) had no experience litigating constitutional cases, was stumped how to get back into court . He called his former professor at Georgetown, who connects him with another lawyer, Phillip Hirshkop. Their conversation wasn’t precise. but Hirshkop said something about filing a 1983 action against the state judge.

Later in the movie, Cohen tells the Lovings (who at that point were quietly living in a house in Virginia) that they filed a motion to vacate the sentence with the Caroline County Circuit Court. However, the judge “stonewalled” the motion. In fact, it was pending for more than a year. Cohen told Loving something about filing a complaint in federal court. In fact, the ACLU filed a class action in the Eastern District of Virginia, seeking to invalidate the miscegenation law. Shortly after that complaint was assigned to a three-judge panel, the trial judge in Caroline County issued his decision, denying the motion to vacate. It was this decision that generated the infamous passage quoted liberally in Loving.

‘Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents. And but for the interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.’

Cohen read this passage aloud to Loving, and stressed how it would help his case. Loving could not understand how losing the case in the trial court could possibly be a good sign. (All too often, lawyers take for granted what it means for a “test case” to lose in the lower court).

Once this decision was issued, an appeal was filed with the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals. In the film, a random building (not the court) was labeled the “Virginia Supreme Court.” (I’ll let the naming error pass). To speed things up, the court managed to hear arguments, and issue its decision on the same day before the Lovings could even make it to their car. With that, their case was appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States. Cohen later told them that SCOTUS granted review, and explained that they had the right to appear at the oral arguments. Richard said no. He was not interested in drawing any more attention to the family. Mildred would not go unless he went. The lawyer said something to the effect of “The Court only grants 1 out of every 400 petitions.” If only the odds were so good.

The next scene made me yell at the screen. Really.

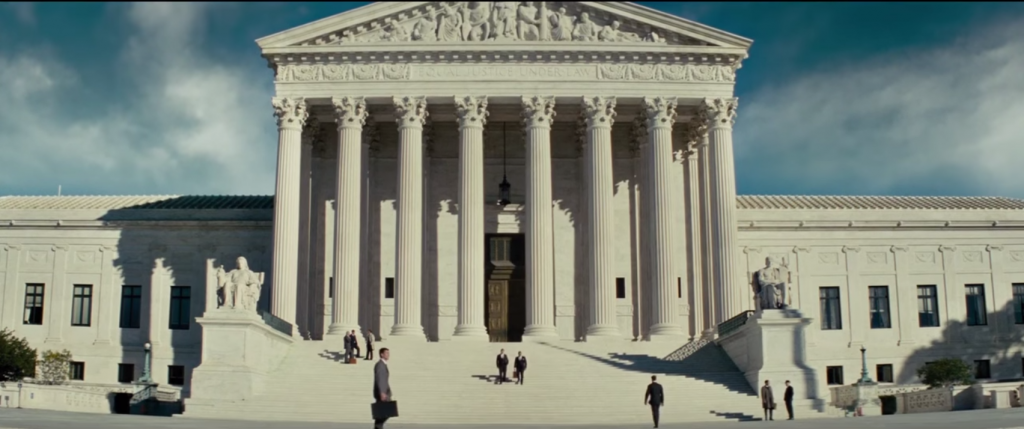

Several cars pull up along a residential street with trees in the background. Cohen, Hirschkop, and others get out of the car. One says, “are you ready?” They look forward. In the next scene, the shot cuts to archive footage of the Supreme Court. NO!!!!!!! Across the street from the Court is the Capitol, not a random residential street. Why would they make such an awful, unforced error?

In the next scene, you see Cohen and Hirschkop argue separately before the Court. They deliberately blur the faces of the Justices. All you can discern is that they are sitting in front of a red curtain.

I was listening to the oral arguments on the ride to the theater, and as best as I could tell, the writers lifted this passage verbatim from Hirshkop’s opening statement.

You have before you today what we consider the most odious of the segregation laws and the slavery laws and our view of this law, we hope to clearly show is that this is a slavery law.

After the arguments were made, the Lovings phone rings. It was Cohen–he told Mildred that they had won! It was a powerful scene. Most of the theater was crying.

All in all, it was a solid movie about the Supreme Court. It didn’t quite get the posture exactly right, but faithfully executed the constitutional discourse.

As an aside, in reading through the decision by the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals, I learned that six months after Brown v. Board of Education was decided, SCOTUS denied certiorari in a challenge to Alabama’s miscegenation law.”Jackson v. State, 37 Ala.App. 519, 72 So.2d 114, 260 Ala. 698, 72 So.2d 116, cert. denied 348 U.S. 888, 75 S.Ct. 210, 99 L.Ed. 698.” From this, the Virginia court did what we were not supposed to–infer something from a cert denial: “The United States Supreme Court itself has indicated that the Brown decision does not have the effect upon miscegenation statutes which the defendants claim for it.”

I also did not realize that the Virginia Court ruled that the Loving’s sentence was “so unreasonable as to render the sentences void.”

When the defendants’ sentences were suspended, the purpose which the trial court should reasonably have sought to serve was that the defendants not continue to violate Code, s 20-58. The condition reasonably necessary to achieve that purpose was that the defendants not again cohabit as man and wife in this state. There is nothing in the record concerning the defendants’ backgrounds or the circumstances of the case to indicate that anything more was necessary to secure the defendants’ rehabilitation and to accomplish the purposes envisioned by Code, s 53-272.

It was, therefore, unreasonable to require that the defendants leave the state and not return thereafter together or at the same time. Such unreasonableness renders the sentences void and they will, accordingly, be vacated and set aside. The case will be remanded to the trial court with directions to re-sentence the defendants in accordance with Code, s 20-59, attaching to the suspended sentences, to be imposed upon the defendants, conditions not inconsistent with the views expressed in this opinion.

In other words, the requirement that they leave the state in no way served the purpose of the penal statute, because they were still cohabiting as married. The sentence could only have required them to stop living as married. Thus, after the Virginia Supreme Court’s decision was vacated, they were technically allowed to live in the state as husband and wife–until they were arrested and sentenced to prison.

Also, during the arguments, Cohen moved for Hirshkop’s admission pro hac vice, before the arguments began! Can you imagine something like this today:

Warren: Number 395, Richard Perry Loving, et al., Appellants, versus Virginia. Mr. Hirschkop

Cohen: Mr. Chief Justice, may it please the Court. I’m Bernard S. Cohen. I would like to move the admission of Mr. Philip J. Hirschkop pro hac vice, my co-counsel in this matter. He’s a member of the Bar of Virginia.

Earl Warren: Your motion is granted. Mr. Hirschkop, you may proceed.

Hirschkop then spoke for two minutes, uninterrupted, without a single question. Those were the pre-Nino days!